Warm-up

Before we begin, I need you to do something. This is a text about movement, and it will work much better if you move a little more consciously while reading it. I kindly ask you to make a rather inconspicuous motion to begin with, and everything else is up to you.

What happens next depends on where you are. Please find a bird. An image of a bird – a member of a group of more than 10,000 species1 – will work too. You could look one up on the internet. An image of a bird behind the glass of your computer screen would be quite fitting. After all, this story brings us to the Australian Museum in Sydney, where taxidermy birds are strung up from a ceiling, or sit in a chest of drawers. Most of them, however, are mounted behind glass.

Have you found one? Then, please, with the fingertips of your right hand, gently trace the outline of the bird on the screen. With your left hand, trace this same outline on your body.2

Maybe you could stand up and go to the closest window too, tracing the outline of a bird you see outside on the windowpane. This is what I am doing right now – standing at a window, looking through the glass, seeking birds to trace on my own skin. I found a small sparrow. It is not easy to trace. It moves around all the time.

Overview/Track

Thank you. Please remember these small movements. The text that we will wriggle through together is a practice-based report on a participative choreographic intervention at the Australian museum. Amongst many other taxidermy specimens, a variety of birds are stored there behind glass. You just followed a movement instruction from said production, called “Send out a Pulse!”. The article discusses this immersive audio walk, made by “How to Not be a Stuffed Animal”,3 an artistic-scholarly duo of which I am one half. The piece is a downloadable digital audio walk with a focus on movement and one of the outcomes of a collaboration between a choreographer, Laurie Young, and myself, a cultural anthropologist. In our work, we appropriate the medium of the audio guide, a staple at most museums, and develop digital, downloadable productions that offer choreographic scores – suggestions for movements – to participants. These zoom in on the topic of taxidermy – both in concrete terms and metaphorically – and invite and challenge participants to consciously explore their own fleshiness and to generate movements of thought and within the sensorium that tackle boundaries between inanimate and animate, human and more-than-human.

Artistic interventions especially in art museums and galleries have proliferated during the last decades. These are not movement or performance pieces that happen to be shown in museums, but pieces that problematize the museum as an institution. Performance artists like Andrea Fraser and Tino Sehgal have offered well-known institutional critiques that speak strongly to our work because they activate the museum space through creative play with the everyday performativity of museum encounters by appropriating the guided tour. In Andrea Fraser’s famous work Museum Highlights (1989) for instance, she takes on the persona of a tour guide at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. During the performance, she points out the museum’s features and artwork in an overly grandiloquent way, exposing the pretentiousness of the art world’s everyday rituals. An important forerunner of feminist institutional critique, the piece is especially interesting to us because it entwines spoken language and the gestural, expressive body and exposes guided tours as world-making performances with known (at least to members of the artworld) rules.4

Working with the movements of museum security staff, gallery front desk receptionists etc., Tino Sehgal’s work challenges visitors/participants into interrogating their own reactions to the disruption of known patterns of interaction at the museum space:

In its classical form, the museum views you as a subject. […] There was a democratic process that constructed culture and, when you entered the museum, you received this culture, just as you would receive orders from the king. I don’t think that’s the case in our society. We are constantly constructing culture. So when you enter my work, you are also constructing it. (Sehgal in Peiken 2007, online)

Note how in Sehgal’s reflection of his own performance he highlights the rule-informed behaviours of visitors while simultaneously drawing attention to their ability/inevitable re-making of those rules each time they enact them. Sehgal’s performances include Kissing Guards, where a pair of museum guards in a variety of gendered constellations, start kissing when visitors approach them.

Other choreographic interventions provoke new experiences and thinking about museum architecture and the inertia of the artworks it hosts. In choreographer Trisha Brown’s well-known piece Walking on the Wall (first shown at the Whitney Museum in New York in 1971), dancers suspended from the ceiling in harnesses moved horizontally along the walls and thus “explore[d] gallery and museum as a way to challenge the spatial and temporal limitations inherent to traditional proscenium presentation” (Shropshire 2015). Other dance pieces like Museum Interventions by William Forsythe (2014) at Lipsiusbau Dresden ask how choreographic objects influence the reception of conventional, static art displays in museums. These works serve as examples of how the architectural forms of the museum can be put to work so that alternative ways of moving and meaning-making can be explored.

Natural history museums have become more common sites for artistic interventions of late. They cooperate with artists as they hope to attract new, nontraditional audiences, and in an effort to create space for self-reflection and transdisciplinary stimuli. The intention is that “interspaces” where institutional rules and scientific norms are temporarily suspended can provoke fresh thinking (Berthoin Antal 2019: 45).5 Artistic interventions in museums of natural history often address taxidermy and dioramas displaying taxidermy. Mark Dion and Janet Laurence are artists whose work is especially well-known in that context and they have, amongst others, cleared the path for a more general acceptance of artistic interventions happening in natural history museums, who do not traditionally feature work that is considered “artistic”. Janet Laurence has produced site-specific installation work (including exhibitions at the Australian Museum, Museum Koenig in Bonn, and the International Garden Exhibition in Berlin) including taxidermy from on-site collections, found objects, photography/projection and other elements that speak of care, alchemical transformation, and hybrid naturalcultural environments. Mark Dion’s body of installation work reflects critically on cultures of collecting and scientific knowledge production and often involves taxidermy. For example, in The Tar Museum (Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, 2017) he shows large birds covered in tar, like geese and flamingos, atop of their transport boxes.

In terms of choreographic interventions, Laurie Young (How to Not be s stuffed Animal’s other half) and set designer Heike Schippelius collaborated for Natural Habitat (2011), staged at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. Based on extensive research with climate researchers, they created a diorama set in a post-apocalyptic future where the dancer (Young), who is constantly interacting with other species under the fluctuating conditions of climate crisis, is both an active witness to catastrophic not-so-future times and a museum artefact that seems to be speaking of the past.

The great pleasure of this report, a written piece, is that it allows some stories that have informed the work for the piece to breathe, those that never made it into its finished form, which follows the logics and form of movement and affectively charged emplacement and not the one of detailed description and a rather linear, textual mapping. A focus of the article will be on encounters with some of the many birds presented at the Australian Museum. This is not the main focus of the original walk, which creates situations and positions that open up to broader questions of the making and unmaking of boundaries between subject and object, “animal” and “human” by zooming in on a medium for movement shared by many life-forms: air.

Focusing on birds’ extinction stories, I will unpack some general considerations that can make such interventions provocations for attentive emplacement, for a “praxis of care and response” that creates possibilities for response-ability and conscious situatedness (Haraway 2016: 105). This is achieved through human bodily attunement which does not provide finite answers but brings up disruption that can make the posing of those questions more immediate. As Donna Haraway so rightly points out, referencing her own practice of storytelling, a practice of weaving a web of potential openings might create points of temporary attachment that strengthen this goal. Response, here, really is a visceral happening: being affected through a shift in the sensorium and through temporal irritations both for the participants and the onlookers (see figure 1).

Through a focus on (some) birds and by sharing the materials of the production for the Australian Museum, I argue furthermore that taxidermy and choreography are both practices of creating patterns or forms of movement. Like the track of Send out a Pulse!, moving from the entrance hall to the rooftop cafeteria, this article unfolds through several episodes. The first section explores the question: What can a focus on movement contribute to understanding multispecies worlding?

From this discussion of the everyday, as well as the consciously staged dance that shapes the mutual modulation of beings and materials, the text moves on to discuss taxidermy as a human practice that complicates the boundaries between organic and nonorganic entities (Kalshoven 2018). This curious ambivalence is the core interest of the duo How to Not be a Stuffed Animal, and the section below exploring this duo’s work details both taxidermy’s anthropocentrism and its potential to be otherwise if moved differently. The section also analyses how taxidermy and choreography both can be understood as mutually inspiring forms of creating a relational field through movement.

As this discussion takes the form of a story about birds, the final part of the text presents this story, tied together with movement impulses in thought and physical action, about taxidermy birds found at the Australian Museum, birds living in Central Park in New York, an after-work stroll leading to a great discovery, women’s fashion, and the birth of an insight: that humans can put a dent in nonhuman animals’ population. The report ends with some statements on the potential of choreographic audio walks as provocations to attend, notice, and attune differently and beyond the colonial/scientific sensorium (Myers 2017) that scaffolds museums of natural history.

Choreographing Museal Bodies from a More-than-human Perspective

I am standing on the rooftop of the Australian Museum. Over my right shoulder, three levels below is Sydney’s Hyde Park – I know and remember it rather than see it – with its Hills Figs trees. I can sense their greenness, basking in the sunlight, and their greyish bark. I look forward to seeing them again later, transformed.

A second ago, I opened an unassuming glass door on the left side of the cafeteria. A voice coming through my headphones has guided me here. I close the door, and the smells of fries, coffee, and grilled sandwiches dissolve. The air is warm on my face; a soft wind is blowing. It’s moist outside, and much warmer than it was during the last hour. I look straight ahead. Before my eyes, pipes and ventilators pierce through the stone walls of the museum. Here, on the fourth floor, the roof, next to a group of bouncing kindergarten children, the air conditioning system that keeps the air inside the museum cool and dry connects to the weather world outside. The sky. The clouds. The sounds of the distant traffic. Cool and dry air, created mechanically to keep the organic materials at the museum – feathers, bones, fur – from rotting, meets the warm and moist air that carries Sydney’s airborne life-forms and circulates in and between our breathing systems.

I am excited, and anxious, because I have been following a small group of museum employees who are participating in this audio walk, trying it out, enjoying it, and finding its flaws. For little more than an hour, participants – myself included – have followed a soundtrack. Their testing it is a premiere for the first production of How to Not be a Stuffed Animal.

When participants pick up an audio guide at the cashier desk, or stream the production, they enter a parkour where they are guided by their headphones. A voice is present. It invites participants to touch the metal of the handrails on their left side. Asks them to notice where they are and what mechanisms are in place to guide their attention, their movement. Asks them to notice the different surfaces surrounding them, what possibilities for different modes of encounter. Sensitizing to the fact that one is always sensing.

As the parkour unfolds, moving through sites as varied as elevators, neglected corners in the children’s discovery hall, the foyer, the rooftop, and of course the main exhibition halls, participants are invited to follow the “choreographic scores” they hear, such as “begin to shake your body up and down by bending your knees in quick continuous succession”, which come with a variable degree of detail.

Choreographic scores can be understood as “exercises that draw attention to something other than themselves. Because the rules are so basic and the time between instructions so long, participants become quite mindful of how they are drawn to move or talk in some ways and not others, of how they make choices about how to follow the rules (or not)” (Dumit et al. 2018). Audio guides, which we are referencing in Send out a Pulse!, do indeed carry the notion of “guidance” in their very names. Whether one does follow the instruction is, of course, up to each participant. Young and I think of them as a possibility to succumb to a voice that needs a body capable of travelling the museum building. A voice that needs the participants’ moving bodies, like a taxidermist entraining with more-than-human bodies, to unfold its agency.

The choreographic scores, a form of spoken dance notation (see Klein 2015 on different forms of dance notation), are recorded on an audio device, where they are stored in a file after they have been entwined with narration and a complex sound design by Sydney-based composer, musician and field recordist Trevor Brown. The sound design is based on sounds evoked from haptically engaging (scratching, stroking, knocking on…) with the glass cases of the museum, archival records of species whose lifelines and connections to the museum we were disentangling, and the museum’s air conditioning system that spreads throughout it like an organic respiratory system. The aim, in short, of this mixture of modalities, is to move museums’ audiences through what we think of as more-than-human choreography.

Choreography (very simplistically) means to create possible movements along coordinates of time and space and to create new fields of relations by doing so. To choreograph understood as a verb, serves as a conceptual and tangible tool to “arrange relations between bodies in time and space. [An] act of reframing relations between bodies, a ‘way of seeing the world.’ […] a dynamic constellation of any kind, consciously created or not, super-imposed or self-organised” (Klien, Valk & Gormly 2008: 8). It is thus a relational practice. As Erin Manning points out, likewise, choreography is not about “bodies as such but relations” (2013: 76), a “generative practice” (ibid.) where relations can be felt and explored and even the verbally given choreographic scores are more than linguistic: “When language moves us, it is because it operates in the associated milieu of relations” (ibid.: 77).

Generating and exploring new milieus of relations, we offer a partial perspective that is aligned with multispecies perspectives who seek out new modes of attention and immersion, of knowing and understanding others, based on an underlying bearing: “Life cannot arise and be sustained in isolation” (van Dooren, Kirksey & Münster 2016: 1–2). Rather, the multispecies worlds we inhabit are shaped by and keep shaping coevolutionary histories, biochemical reciprocity, affective, semiotic, and material, symbiotic, or parasitical interconnectedness of abiotic and biotic life-forms (ibid.). “Relational” does not mean ‘good’ in any moralizing or naïve sense. It merely states a ‘fact of life’: “Human nature is an interspecies relation” (Tsing 2012: 141). Unlike animal studies, multispecies studies involve natural scientists, artists, and indigenous thinkers, and borrow from theoretical outlooks like New Materialism to interrogate the conventional boundaries between animate and inanimate, abiotic and biotic (van Dooren, Kirksey & Münster 2016: 5). Young and I make productions for human museum visitors who have official access to the work by buying a ticket. This is not self-evident and in fact, the creative challenge for future projects may be to do otherwise, to go rogue and/or to explore new audiences that are part of interspecies life (e.g., where might microbes stuck to soles want to go?).

In her work on the Toronto High Park, a grassland forested with black oaks, anthropologist, trained dancer and microbiologist Natasha Myers, who collaborates with dancer and film maker Ayelen Liberona, provokes participants of their multisensory outings to “become sensor” and, by doing so, to “do ecology otherwise” (2017). Responsibility, in the sense of response-ability as outlined above, is very much a question of being affected. During our movement research and ethnographic observations at the museum, we were often surprised at how little time visitors actually spent just looking at taxidermy objects. It seemed that the modes of engagement could be spiced up a little. Slowly breathe on the screen or the paper before you. Do you ruffle any feathers?

In addition to a fundamental questioning of the scientific sensorium’s constraints that permeate museum spaces, questions like “Who has the privilege of moving/being mobile?”, posed by dance scholars like Gabriele Klein (2015: 46), are palpably relevant in a movement piece set in a rigid museum space, where extravagant movement is not encouraged, amongst bodies of more-than-human animals that keep disappearing from this world at an increasing rate and speed together with their individual and collective movement patterns. To rephrase the question, one could also ask: whose experiences and sensory, kinesthetic worlds matter?

Multispecies choreography, then, could be a form of consciously moving that gives space to other life-forms as knots in a relational web that we can surf along for a little while through kinesthetic attunement, guided by scores, expanding and contracting the sensorium in some of the myriad ways in which that is possible. And because movement at the museum is public, much more public than reading a multispecies ethnography at the cafeteria on the rooftop terrace, its potential for interruption is substantial. One might get a response not just from within.

Borrowing words of another Sydneysider, anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose, the walks are there to help trace and enact the “situated connectivities that bind us into multispecies communities” (2009: 87). The key word here is situation: the feeling of situatedness of emplaced bodies whose permeability and whose world making capacities matter.

Understanding presence and absence physically, kinetically, and multi-sensorially is especially crucial in a time of mass extinction, a major event that as yet often goes unnoticed. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the planet has lost half of its wildlife in the last 40 years (IUCN 2015). The mass extinction of species is a concern of museums of natural history whose researchers often feel like archivists of the present (see e.g. the interview of Johannes Vogel, the Berlin Museum für Naturkunde’s director, in Der Tagesspiegel, January 23, 2018; Karberg 2018). Multispecies scholars working on extinction are interested in the ways in which it is “experienced, resisted, measured, enunciated, performed, and narrated in a variety of ways” (van Dooren, Rose & Chrulew 2017: 3). As artists engaging with multispecies scholarship, we are interested in making those tensions and developments viscerally available.

The tensions that Young and I work with do not only encompass the cruel present and future of mass extinction. Our work is also placed in sites that, in spite of their efforts to save and preserve life, are reflective of the many asymmetries that shape human and more-than-human coexistence. Museums put forth cultural hierarchies as well as sensory regimes (Bennett 2018) that naturalize and privilege certain ways of being in the world over others. Museum architectures and safety regimes govern all the bodies that pass through their doors, windows, or sewage canals. The range of actions for lending oneself to an encounter with a postmortem animal, vibrantly mattering and interpreted through specialists’ hands, is prescribed. And in fact, only adequately behaving humans, having paid an entrance fee, are perceived as adequate visitors. The only way for a nonhuman animal to cross those thresholds is either as a taxidermy specimen, as consumable meat, or as an office dog with special permission. The choreographic interventions that we offer are thus always already set in a space permeated by power.

The work of How to Not be a Stuffed Animal suggests that movement is a form that enables us to approach posthuman sociality where bodies of any kind are both individually situated and connected in myriad ways of many different effects and qualities. Adding movement to the mix – or may we say, storying through movement and giving it priority over other means of expression and experience – adds a dimension of felt experience that turn participants not only into consumers or readers, but into objects of the gaze and ethnographers of their own experience in a setting that is concerned with the representation, rather than the enactment, of interspecies relations. Movements can be small or expressive, they play with scale. Drawing the outline of a bird on the back of your hand creates very different potential openings than pacing a vitrine, which is a clear disruption of the usual rules of conduct. You can walk a figure of eight very slowly, almost nonchalantly, or speed up so that the pattern becomes visible, and audible, to onlookers. What will happen? Auto-ethnography through movement can be a tool for multispecies studies.

On the rooftop terrace, the participants are turning right, each at their own speed. They leave the green vents behind and turn around their axis, or cut a corner, take a step backwards. Everyone is facing a new sight now, a new potential path, a new situation. The wind is coming from a different angle. This time, the path is leading nowhere, or rather, everywhere. In front of us is a glass wall, like many others that we have encountered in this building full of display cases. This time, it is a balustrade, made of glass, which reaches up to the level of an adult’s chest. The metal handrail on top feels warm to the touch, heated up by the February sun.

This is what participants are hearing through their headphones, their choreographic scores:

Go to the railing facing the street and the park. Just be. Birds are flying. Remember the bird you traced on your skin. Trace it again. You brought it outside. In Hyde Park below you, cockatoos live in flocks. They have been living in this part of the world for 23 million years. If you stand here long enough, you will see them: galahs and sulphur-crested ones.

They have built communities all over Sydney. Amongst themselves, with other species, humans. Their feathers extract a white powder. If you were to touch one, it would leave a trace on your hands. The powder is floating through the air, going with the wind, up to the stratosphere, settling on the pond below you, the spider webs, trees, the cars and ferries.

I see a young man touching the skin of his left inner arm with his right index finger. His right hip leans onto the glass railing. His whole body is slightly curved. His gaze moves to his wrist. The index finger wafts up, forming a slight bow. The group have brought a finger-drawn outline of a taxidermy bird outside, stored on their skin.

Like taxidermists, like the nonhuman animals that were turned into specimens, and unlike taxidermy mounts, human visitors come to the museum with a body still living and full of potential. Potential to encounter and to be moved, physically and affectively, in a range of ways. And now, stepping outside that door, they are immersed in the weather. The particles of dust, carpet, taxidermy animal hair that have settled on their skin and clothes are mingling with exhaust gases, the dander and feather dust of cockatoo wings, water, and air-bound insects. The participants in the walk had each traced the outline of a mounted bird on their arm and another part of their body halfway into the walk, setting one of its aspects, its outline from a certain angle, in motion.

In what follows I will explore the relationship between choreography and taxidermy practice in more detail, and argue that taxidermy is not only in itself a bodily practice that requires what Kalshoven (2018) describes as kinesthetic empathy, but that it shares important differences and similarities with the practice of proposing movement.

Taxidermy and its Moving Bodies

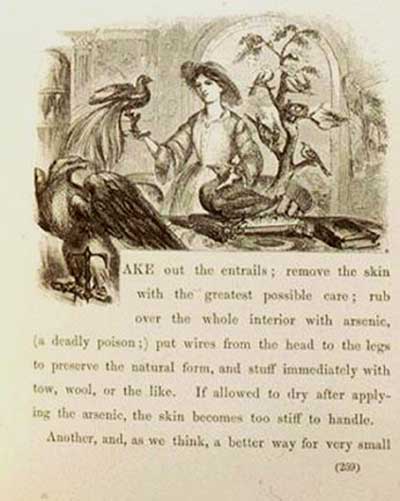

Taxidermy is the daedal preparation of dead animal bodies, a “craft practice of preparing and mounting animal skins so they appear ‘lifelike’” (Patchett 2016). Although the preservation of skins is an ancient proposition, taxidermy in its current form is a child of the nineteenth century’s infatuation with natural history. When hunters, businessmen (and women, as we will see later), and scientists from urban centres of the Global North explored and exploited the ecosystems to which colonialism gave them access, lines of trade, curiosity, violence, wonder, and scientific fascination began to weave around the globe (see e.g. Aloi 2017). Specimens yet unknown to New Yorkers, Berliners, or Parisians appeared in the newly-founded museums of natural history. It was often the case that the nonhuman animals from which they were made had led a short life in the public zoological gardens that also emerged at that time. Taxonomy, the identification and ordering of species and a foundational technique of zoology, today performed by genetic analysis, would have been unthinkable without taxidermy. At the same time, the affective power of the living beings-turned-specimens was strong, and continues to be so. As curator and writer Rachel Poliquin points out, taxidermy was and continues to be an expression of human longing and desire, the desire to remember, to wonder, to praise, to adorn, or to collect: “Taxidermy exists because of life’s inevitable trudge towards dissolution. Taxidermy wants to stop time. To keep life” (2012: 6). The making of taxidermy objects, as we will see again later, became a bourgeois pastime of the Victorian Age. One popular reference work (also discussing aquariums, magic lanterns, and shell work) describes the technique in quite accessible terms:

Take out the entrails; remove the skin with the greatest possible care; rub over the whole interior with arsenic, (a deadly poison; [sic!]) put wires from the head to the legs to preserve the natural form, and stuff immediately with tow, wool, or the like. If allowed to dry after applying the arsenic, the skin becomes too stiff to handle […]. (Urbino et al. 1864: 259)

Take a closer look at figure 2 within this text. What do you see? Please look at the pictured lady’s right lower arm. It is bent upwards. There is a weight on her fingertips. She must be grabbing the bird’s feet rather firmly, as his weight seems to be shifting away from her. A heavy feathered tail, longer than the bird’s body, cascades behind. Two pairs of eyes. One of the pairs, by all likelihood as was and still is the style of the time, is made of glass; not looking anywhere anymore. A tree dweller, claws made to grab onto branches, now locked onto a hand. Another pair of eyes looks at the bird. We can assume from the context that the taxidermist’s eyes are not made of glass. Think about the outline of the bird you drew on your arm. Can you still sense it?

The popular DIY book Art Recreations: A Guide to Decorative Art provides advice on creating taxidermy for amateurs (Urbino et al. 1864).

Although the actual making of a taxidermy mount requires great experience and skill, much more, in fact, than the short text excerpt suggests, the living beings that are turned into specimens and decorative objects through such handling have something in common regardless of who made them. Taxidermy is a human practice focused on more-than-human bodies. Mounting a nonhuman animal as a taxidermy specimen is an act “of setting animals apart, classifying them, and an attempt to get closer to them” (Kalshoven 2018: 44). They are both fact and fiction, materiality echoing a nonhuman life and yet transformed through a process of human making that is, even though its goal is often naturalism, highly interpretative.

This act of interpretation through craftsmanship is expressed through movement, posture, and position. As cultural choreographer and avid ethnographer of taxidermy practice Merle Patchett (2016) has pointed out lately, taxidermy constellations of nonhumans and humans become entangled in their fleshiness firstly through the process of making. The making of taxidermy is a skilled practice that is “co-authored” (2016: 15) by the agency of the material, the taxidermist’s teachers’ skills that resonate in their body, and their own idiosyncratic style of making that developed within that assemblage. As Petra Kalshoven so rightly points out, giving shape to a taxidermy specimen is an ethical decision: “morphological approximation” (2018: 35), the kinesthetic quality of a mount, is what animates it. Rarely does one see a specimen appearing dead, or even sleeping. They are frozen in motion, and whether mobility or immobility come to the forefront during the act of looking depends on the taxidermist’s skill as much as on the viewer’s perception. The skill of each and every taxidermist we worked with was absolutely outstanding, and yet they might be locked in micro-movements that their living body would never have experienced or tolerated. Approximation, however, is expertly tried. Writing about the mounting of a bird, anthropologist Kalshoven notes that “(p)rofessional taxidermists not only draw on their knowledge of morphology – they also constantly strike poses, referring to their own bodies and its appendages, imitating bird posture and movement” (2018: 35). This kind of bodily kinship, not to be mistaken for animistic animation, is expressive of an ethics of morphology: the wish to work with utmost care to further blur the boundaries between death and life. A specimen thus mounted is met, in the museum space, with visitors and staff that do not come from this cultivated depth of engagement.

Taxidermy specimens and humans come together through encounters in time and space: “(e)ncounters are […] spatial; encounters spatialize. Not space as container, but an interweaving of trails, tracks and paths” (Barua 2015: 266). The museum-as-container is full of vitrines – as containers, containing bodies-as-containers-of-information either in isolation or in dioramic arrangements that speak of taxonomical or ecological relations. But the walls of glass and concrete, fur and skin, become permeable once the tracks, traces and lively potentials of more-than-human and human bodies-as-actors are activated. These encounters with taxidermy nonhumans and their human-made habitats could enable participants to open to the experience of nonhuman communities and individuals situated in a space made for and by privileged humans. In Sydney, we played with the trope of the human body being one entwined with other bodies – other-than-human, human, taxidermy, or infrastructural – that are encompassed by an architectural body to enable that encounter. The following situation may illustrate this.

Participants have just entered the museum foyer. It is the beginning of the audio track. They have performed a “body check”, tuning into their own bodily awareness, and walked up a ramp. I am walking along, headphones over my ears too. The music has begun to play. Our left hands slide over the metal surface of the handrails. The sound, the scratching on metal, resonates in our ears. My left palm will still smell like metal an hour later, at the end of the walk, when I am on the terrace.

A few strides to the right, and our steps soften. The ground on which we walk has changed. A large open space unfolds in front of us. Covered in grey carpet, high-walled, and with a glass roof. The movement of weather and light is perceivable. We listen, and are greeted by the sound of bushland, and then the sound of a car park.

Why? Because the Australian Museum has been built on a forest – bushland that covered what is now Central Sydney, of which the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation are the traditional custodians. The arrival of European settlers was a huge and deadly shock not only to Aboriginal communities but also to the local ecology, which was and continues to be hugely transformed by the introduction of new species and deforestation. Only one percent of the Sydney blue gum (Eucalyptus saligna) forests persist today, cleared away by early farmers and the generations of new migrants that followed them (Bradshaw 2012). The roots of the physical museum reach down into that forest ground.

The museum’s architecture, built by humans and carriage horses, and occasionally dogs pulling a carriage, was made to showcase and translate Australian natural history, often represented through taxidermy, for Western colonialists in a flourishing city mirroring the metropoles of the Global North. Since 1827, when it was first established as the Colonial Museum and later renamed, it changed and transformed along with the city of Sydney. The space where I am standing now, with a group of participants testing the piece, in the atrium with its grey carpet, used to be a car park with a grey concrete floor in the 1970s. On my right-hand side, a sandstone wall rises up. It used to be an outside wall of the building and housed the museum entrance, before a glass appendix to the original building turned it into an inside wall. Now, read about what happens next, around six minutes into the walk:

Slowly turn around your axis and look around. The atrium is a meeting place for humans to socialize. It is a place where humans decide which path to walk. Left, right, up, down. Like many other organisms, this building has a skeleton. A skeleton made of glass, metal, sandstone. Here we are in the thorax or the chest.

Inside the thorax are the ribs and sternum. It houses the heart and lungs.

Take a look at the vents underneath the top balcony. Do you notice a long, glittering red ribbon blowing next to the fourth vent to the left? The building is breathing, too.

Now bring your attention to your chest and breath. Don’t change it. Just notice it.

As you begin to move your breath changes naturally.

In the museum foyer, eight minutes into the walk, we are now running in circles. The grey carpet below my feet starts to fly away as I move faster, enjoying the feeling of running. My whole upper body is tilted to the right, towards the centre of the circle I have yet to make. My arms swing along. This is what we move to:

The air you are breathing is filled with dust and specks of feathers and fur, scales, and skin. It is filled with funghi spores, ashes, exhaust gases, water, and particles from meteors that once burned up in the atmosphere. Below you, the surface of the ground.

As you walk in this circle, you too are leaving traces of dust and movement. How many organisms have trod this space? How many more will come?

Your heart rate is speeding up. You are alive in this space.

Keep walking and slowly increase your speed.

If it is safe to do so, you might even get up to a jog.

And so, we speed up to a jog. People stare at us. The security guards have been prepped, though. After a few incidents where visitors have alerted them to our erratic behaviour, they know what to say: “this is art” or “they are making an audio guide”. It clearly matters how one moves here, and the range of acceptable motion is neatly mapped out. People move at a certain pace, spending an average amount of time looking at specimens, keeping their voice low. No one walks backwards or sideways, crawls or lies down. Out of the endless possibilities of how to move and position our bodies, kinesthetic choices are made every minute of the day. We are choreographed, and choreograph others according to context, situation, and learned and encultured forms of carrying oneself: “When we arrange the furniture in our house, we are creating choreography. When we speak softly, requiring the listener to lean forward, we are creating choreography”, according to performance artist Janine Antoni (2016: 2).

According to art historian Giovanni Aloi’s writing on speculative taxidermy in contemporary art, “the taxidermy object is a sign, a symbol, and a trace that rests on institutionally constructed truth. However, this truth, in contemporary art, is characterized by an important fluidity that renders it unstable and precarious” (2017). From the perspective of movement, one should add: this can be true not only of the taxidermy object, but the practice of taxidermy itself. Taxidermists create movement and possible relational fields, they too do choreographic work. At the same time, the physicality of the remains of the nonhuman animals choreographs, bodily addresses, and affects taxidermists, but less knowledgeable onlookers as well. “Biotic lifelines”, being alive in biochemical terms, is thus not an exclusive criterion that species, individuals, or specimens need to fulfill to be part of the dance (van Dooren, Kirksey & Münster 2016: 4). Allowing oneself to move along a track along the museum, participants give, if they choose to, permission to be “taxidermied” – put into a specific bodily mode – so that the taxidermy specimens at the museum can be animated. The effects of this kind of animation differs, of course, from participant to participant. However, “(n)obody – ‘no-body’ can learn an unfamiliar neuromuscular pattern without being willing to acquire a new and perhaps startling into who it is they actually are – that is to say, a truly plural being or figure” (Ness 2016: 15).

Choreographed taxidermy, choreographed bodies in human-made sites of representation, do not necessarily tell naturalist stories about the species that they have been made to represent. Neither do they mirror the density of the complex multispecies ethnographies that have emerged during recent years. They make a different proposition: that fleshiness is what species and individuals share, and that, through movements of the body, movements of thought might germinate.

More-than-human Choreography in Times of Extinction: Birds of Paradise and the Figure of Eight

Imagine a different city, this time on the Northern Hemisphere. The air a little cooler, later in the year. Less moist. In New York City, in 1866, a gentleman has just left another museum, the American Museum of Natural History, where he is the chief ornithologist. The main entrance of the museum, his workplace, looks over a park too: Central Park. He looks forward to crossing it on his way home. The New York Central Park of the late nineteenth century, again designed by human and more-than-human labour, is overgrown with forested areas: more than 20,000 trees – American elm, beech, yellowwood, cedar, cork trees, pine and hornbeam, meadows and streams and bushes. Over 200 species of birds live there, either permanently or as a stopover while they migrate along the East Coast in spring and fall. Wherever his gaze goes, wherever he lifts his eyes – closely, or up to the sky, looking for hawks, he can see and hear birds.

After a good stride, he turns onto Fifth Avenue. The birdsong fades away. But he still sees birds everywhere. He lowers his eyes, used to scanning the sky and the trees for them. In fact, all he has to do now is to look straight ahead. Flocks of birds move around him, and come his way. He makes a detour at the very last moment. He holds his breath, blocking out not exhaust gases like we do in Sydney, but the smell of horse dung. This happens more than 130 years ago. Frank M. Chapman, the ornithologist, is surrounded by dead birds. Those birds seem lifelike, their bodies curved, looking like they have been caught mid-flight. Is this a dream? Is this one of his famous dioramas, inhabited by lifelike birds caught in motion? It is not. It is fashion. This afternoon, and on an additional walk, Chapman spots more than 40 indigenous bird species, plucked, reassembled, mounted, and riding on most of the seven hundred hats of New York City’s fashionable ladies that he encounters that day: grebes, sanderling, blue jay, ruffed grouse, blackpoll warbler, mourning dove, snow bunting, eastern bluebird, and many more. Chapman and some of his contemporaries, predominantly middle- and upper-class women of some means, are sauntering along Fifth Avenue during the climax of the plume trade.

Frank Chapman was not only the creator of the natural history museum’s famous bird dioramas – showcases representing ecological relations, featuring the birds amongst foliage and other bird species specific to certain locales. As an ornithologist and biologist, he was convinced of the value of counting to predict population growth and development (Haraway 1989: 88). And thus, he counted: “Five hundred and forty-two out of seven hundred hats brandished mounted birds. There were twenty-odd recognizable species, including owls, grackles, grouse, and a green heron” (Penna 1998: 97). Strolling along Fifth Avenue, counting, doubtlessly taking careful notes, Chapman moved along an important knot in the global trade with local and exotic birds that came to be known as the plume or millinery trade. This was an event that eventually created public awareness for an as-yet not fully realized fact: that human activity could put a dent in a nonhuman animal’s population. New York and London were centres in the millinery trade (Patchett 2011). Not only local birds were mounted on hats.

From 1905 to 1920, 30,000–80,000 bird-of-paradise skins were exported annually to the feather auctions of London, Paris, and Amsterdam (Kirsch 2006: 16).

At the Australian Museum, this line of history is caught up in a vitrine. Perhaps you can imagine participating in the walk again? You would now be entering the Wild Planet hall of the museum. This hall is dedicated to global biodiversity. It speaks of the tree of life through words and images, and labels detail how the species that the mounted specimens are meant to represent are threatened by extinction. The hall holds a mount of the Tasmanian tiger too, a sad icon of extinction history. As one enters from a side entrance, passing through a glass door, one’s sight may easily be drawn upwards. In a tall glass cabinet, a white, abstracted structure seems to grow out of the museum floor like a tree.

Just in front of you is a tall glass cabinet full of birds collected over the last 200 years. Walk towards this cabinet and stand at a close distance to it. Slowly breathe on the window. Are you ruffling any feathers? Do you remember the outline you traced from the bird box upstairs? Can you re-trace this bird into the vitrine that is in front of you now?

Can you trace the line you drew in the very beginning of this text onto figure 3?

This white tree is occupied by birds from around the globe, with a focus on Australia and the Pacific. Last but not least: the so-called birds of paradise. Please take a closer look at the image. In its lower third section, on the left side, you can see the long tail feathers of a male greater bird of paradise (Paradisaea apoda), pointing left. The upper body is out of sight.

Paradisaeidae, the family of birds known as birds of paradise, do not migrate while alive. They are endemic to Papua New Guinea. Birds of paradise come in many species, and of course this is not how they would call themselves, or how any of the Papuan communities who were originally entwined with them would name them either. Europeans called them birds of paradise because paradise is always elsewhere, and because their beauty seems unearthly (Brunner 2015). If one looks for sources about birds of paradise today, one immediately encounters an abundance of movement, complex movement sequences, improvisation, and synchronization with other birds.6

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, of course, the perception of birds of paradise was very different. Video footage that is available to us today shows bending bodies that, with their claws, anchor themselves on twigs and trees to execute complicated movements. For a long time, people in the Global North did not know that birds of paradise had legs. The taxidermy technique employed by the local communities in Papua New Guinea entailed removing the legs, and sometimes the beaks too (Kirsch 2006: 17). These parts of the body seemed unpleasant, and were unnecessary in their locally important ritual and decorative use as headpieces. For Europeans, however, the state of the legless birds sparked the idea that these birds never touched the ground and always flew, moving in the sky, close to heaven: hence the name birds of paradise (Brunner 2015). Both their plumage and their behaviour, which was epitomized by their highly expressive mating dances, sparked the colonial and consumerist imagination (De Vos 2017: 3). Papuan communities had long noticed and studied the birds that coinhabited their dwelling sites, were intimately familiar with their behaviour, and integrated inspiration from their movement patterns into their own ritualized kinesthetic expression (De Vos 2017: 96f.).

The inhabitants of Papua, avian or human, both became asymmetrically entangled in the millinery and taxidermy trade of the late nineteenth century that sought exotic birds and transformed them into decorative objects, mounted specimens for museums and private collections, and skins. The latter were used by milliners who equipped the well-to-do ladies for their own social choreographies, wearing dead avian athletes, mounted in spectacular poses, on their heads: “(t)he bodies of birds of paradise became discursively and figuratively hollowed out and dismantled in this spatial practice […]. Birds of paradise were returned as plumes: signs of transferable beauty and rarity” (De Vos 2017: 17).

Why is a bird allegedly never touching the ground important for the piece? Imagine moving around the vitrine in the following manner, and we will get one step closer to the answer:

Slowly begin walking around the vitrine in a clockwise direction with your right shoulder closest to the cabinet. This could be a tree, or a stalagmite. Keep circling the vitrine three times.

Round one: focus on a bird that is at a low height in the vitrine. Round two: raise your eyes to a bird on the middle level. Round three: look at the top most level.

When you have finished your three rounds, stop and let your gaze calmly wander down the birds. Search for the bird number 20 and read its label.

Three turns around a tree, maybe circling back in time. Becoming disoriented. Maybe being reminded of a hunter’s gaze, a skilled eye. Becoming attentive. The movement stops. The label speaks of the human who may have mounted the bird: Jane Tost. She was the first woman taxidermist the Australian Museum ever employed and had trained with famous taxidermist John Gould at the British Museum before emigrating to Australia (Harrison 2011: 62f.). Together with her daughter, Ada Rohu, she worked in Sydney from 1856 to 1900 (ibid.). Archived photographs show Jane Tost with a hat decorated with an egret; a bird popular as hat decoration during the time. Both mother and daughter were very successful in taxidermy competitions, but eventually they opened a curiosity shop where they sold mounted specimens and skins from the Australasian region for decorative purposes and millinery around the globe (ibid.). Jane Tost and Ada Rohu were part of the global trade with birds that eventually led to the almost-extinction of some bird species and to the emergence of the conservation movement. Led by women, and not without moralizing undertones that called out female vanities but not its mostly male profiteers, the conservation movement led to the creation of the Audubon Society, protecting birds, and other initiatives across the Northern Hemisphere that finally propelled legislation that embanked the global trade (Patchett 2011). In New South Wales, the home of Jane Tost and Ada Rohu, societies that championed animal protection towards the end of the nineteenth century, “had active women’s branches, including the Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the Animals Protection Society” (Sear 2005).

Birds as objects are researchable in museum databases and collections. Details of where and when they were caught and collected, and who mounted them, can often be found.7 The expertise with which they have been mounted speaks of the kinesthetic care and responsibility that went into their making. Most of the time, a label speaks about their Latin name, gender, and the region from which they came. As Thom van Dooren writes, however, species – a troubled concept anyways even for the biological sciences (Hartigan 2017) – are more “than an abstract binomial on a long list of threatened species, but a complex and precious way of life” (2014: 8). In the archive, the taxidermists’ biographies seem to be easier to grasp than the particularities of the life histories of the nonhuman animals they mounted. In his ethnography of birds at the edge of extinction, van Dooren, a philosopher by training who works through extensive ethnographic practice with birds and humans, conceptualizes species as “flightways”, acknowledging the “embodied intergenerational achievement” (van Dooren 2014: 27) of birds that brought their descendants into being through care, inheritance and nourishment (2014: 28). Species, to him, are “lines of movement” through time (ibid.), embodying a particular way of life in which “individual organisms are not so much ‘members’ of a class or a kind, but ‘participants’ in an ongoing and evolving way of life” (2014: 27). I would like to make a point for thinking about taxidermy and its bodies and movements in a similar way. Ada Rohu learned the tricks of the trade, the practice of taxidermy with all the kinesthetic care and responsibility that is tied to it, from her mother, Jane Tost, who came from a family of famous London taxidermists; she had been trained at the British Museum. Their skill and imagination, the movements of their hands and bodies when mounting a specimen, were particular and yet doubtlessly informed by the style of the time. With their skill they encountered numerous nonhuman animal skins, each stripped of the motions that once were part of their flightways, of patterns of life, generation and improvisation that they inherited and invented. In forests and settlements across Papua New Guinea, on hats and in museums around the globe, new choreographies emerged. Birds travelled on hats, moving through the social scenes of Paris, London, New York, or Berlin, frozen in position by hat makers who had not seen them alive, dancing their dances. From ornithologists of fashion and feminist fashionistas, lines of political activity emerged, shifting the tides so the disappearance of some species could be prevented for a while. What patterns of movements got interrupted locally, in Papuan forests, where birds dance on trees not white but green, we can only guess.

From the circling around the vitrine, another movement emerges. A figure of eight. Participants begin to gravitate towards another vitrine, another tree. A figure of eight emerges. Walking towards that other vitrine. Coming back to the first one. Movements that intersect. Lifelines. Flightways?

Attunement, Irritation, Disruption: More-than-human Choreography at the Australian Museum – Conclusion

Send out a Pulse! zooms in on the topic of taxidermy, both in concrete terms and metaphorically. It invites and challenges participants to inflect the museum space inspired by taxidermies’ provocations: to consciously explore their own fleshiness and the questionable boundaries between inanimate and animate, human and more-than-human. The report has unpacked these questions by unpacking a line of choreographic scores and storying revolving around birds’ extinction brought about by the millinery trade.

During the walk, participants are being offered a variety of scores and techniques for sensory attunement that are sometimes entwined with narration. I zoomed into one of the stories that the walk unfolds, the almost extinction of the bird of paradise, and some of its related scores. These include the appearance and disappearance (or forgetting) of an outline on your skin, the circular motion, the guided gaze of hunters. Also, the attunement to air, the medium of movement for airborne birds, and breath, a necessity we share across many life-forms, and that we suggest even the museum building partakes in.

Multispecies studies, that have been inspirational for the work Young and I carry out, challenge some of the basic assumptions that museums of natural history uphold in their public displays: clear boundaries between species and between biotic and abiotic life. Those boundaries are reflected in a highly regularized museum setting that clearly delineates what is approachable and how, what movement is appropriate and what is not, and what stories are worth telling. But in times of dramatic extinction, how can we move otherwise, how can we activate an important ally in a way that makes relations felt and agency unfold?

Choreographic audio walks can offer tools for attunement beyond the colonial/scientific sensorium (see Myers 2017). We provoke participants into close observation guided by smell, perception of breath alongside the museum’s air conditioning system, or to attune to needs of spiders by seeking out dark, neglected spaces where we guide them through visualizations and movement scores where bones dissolve into exoskeletons. Slowly breathe on the screen or the paper before you. Do you ruffle any feathers? This is less to scaffold a new sensorium, and more aimed at setting an already existing one in motion.

Choreographic audio walks can thus offer tools for questioning normalized boundaries between bodies and species. An ethnographic perspective on taxidermy illustrates that choreography and taxidermy share important elements. Both are practices of kinesthetic becoming and they aim at proposing or creating motion, and therefore open up certain forms of relating. The taxidermist’s body is a heavily attuned one, shaped by visceral knowledge and the postmortem animal’s material affordances. While it is easy to see how a taxidermy bird has become undone during the process, it is less acknowledged that the effects are mutual. Scientific taxidermy has helped to stabilize the concept of species and of the human, last but not least by attributing specific movement expressions to any of them. Artistic work on taxidermy has lately destabilized these boundaries especially by playing with hybridity (Aloi 2017). Are some humans, privileged enough to be museumgoers, turned into taxidermy, more-than-human animals humanized, buildings animated into being breathing bodies in choreographic audio walks? I propose that choreographic audio walks at museums of natural history can be tools for visceral complicity with these questions.

Disruption. Choreography, in contemporary discourse, does not aim at representing pre-existing orders. It rather intends to give visibility to the forms and dynamics that create and unsettle them (Klein 2015: 47). An example: At the Australian Museum, visitors often spend but a few seconds with taxidermy. The mounted thylacine (colloquially called the Tasmanian Tiger), a sad icon of extinction in the Australian context, often goes unnoticed in her glass case. When you come near her while doing the piece, you will hear an ascending and heavy breath. If you lend yourself to the scores, still breathing with the building, the dust, feather dander, the spores and microbial life floating through the air, you will soon get caught up in a pattern of pacing. Eyes are on the thylacine. The pacing is the last movement that we know of a thylacine because it has been kept on film footage made at the Hobart Zoo in the 1930s before this endling died. Pacing left to right, right to left. All along the glass of the vitrine. Left to right, right to left. People stop. They start to stare. A new situation has emerged. It is unclear if this is normal. What is it that this person is looking at?

Notes

- The concept of “species” as distinct life-forms is of course a contested epistemological notion (see e.g. John Hartigan’s Care of the Species: Races of Corn and the Science of Plant Biodiversity [2017] for a recent ethnographic study on the topic). I stick with the term for now since it is an important construct within the museum. [^]

- All choreographic scores in italics are part of the original script of Send Out a Pulse! written by Laurie Young and Susanne Schmitt. Other scores not written in italics are made for this text, resonating with the original tone of the piece. [^]

- “How to Not be a Stuffed Animal. Moving Museums of Natural History through Multispecies Choreography” is a multi-year project that is generously funded by the Volkswagen Foundation’s Art and Science in Motion scheme. It creates research-based, movement intensive audio walks. Creative directors are dancer Laurie Young and ethnographer and artist Susanne Schmitt. Anna Lipphardt at the University of Freiburg accompanies our work ethnographically and provides great institutional support. We thank the Volkswagen Foundation for their generous support and their openness towards artistic modes of knowledge production and the Australian Museum in Sydney for their hospitality. Janet Laurence, Thom van Dooren and Eben Kirksey provided great hospitality and support while we were in Sydney. [^]

- On guided tours as choreographic encounters more generally, see Schmitt (2012). [^]

- From 2014 to 2018, the pilot project “Art/Nature: Artistic Interventions at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin”, a cooperation with the German Federal Cultural Foundation, featured works from international artists working in media from sound art to poetry and installation within the museum space. The final publication discusses the potentials and pitfalls of such work (Hermannstädter 2019). [^]

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, for example, provides a curated selection of videos showing the mating dance of greater birds of paradise and ritualized fighting with conspecifics: www.birdsofparadiseproject.com. [^]

- This, of course, is a generalization. Museums are for example often given larger taxidermy collections whose whereabouts cannot always be confirmed. Contemporary scientific enquiry undertaken at research-based museums of natural history focuses on DNA sampling for taxonomic purposes, and only specimens whose origin is absolutely clear can be considered for this. [^]

References

Aloi, Giovanni 2017: Speculative Taxidermy: Natural History, Animal Surfaces, and Art in the Anthropocene. New York: Columbia University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7312/aloi18070.

Antoni, Janine 2016: Choreography. In Terms of Performance, available online at http://intermsofperformance.site/keywords/choreography/janine-antoni (accessed May 12, 2018).

Barua, Maan 2015: Encounter. Environmental Humanities 7: 265–270. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3616479.

Bennett, Tony 2018: Museums, Power, Knowledge: Selected Essays. London & New York: Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315560380.

Berthoin Antal, Ariane 2019: Künstlerische Interventionen erforschen: Was Museen davon lernen können. In: Anita Hermannstädter (ed.), Kunst/Natur: Interventionen im Naturkundemuseum Berlin. Berlin: Edition Braus, 44–51.

Bradshaw, Corey 2012: Little Left to Lose: Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Australia since European Colonization. Journal of Plant Ecology 5(1): 109–120. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtr038.

Brunner, Bernd 2015: Ornithomania: Geschichte einer besonderen Leidenschaft. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

De Vos, Rick 2017: Extinction in a Distant Land: The Question of Elliot’s Bird of Paradise. In: Deborah Bird Rose, Thom van Dooren & Matthew Chrulew (eds.), Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations. New York: Columbia University Press, 88–115. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7312/van-17880-005.

Dumit, Joseph, Kevin O’Connor, Duskin Drum & Sarah McCullough 2018: Improvisation. Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/improvisation (accessed April 22, 2018).

Haraway, Donna J. 1989: Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. London & New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016: Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373780.

Harrison Rodney 2011: Consuming Colonialism: Curio Dealers’ Catalogues, Souvenir Objects and Indigenous Agency in Oceania. In: Sarah Byrne, Anne Clarke, Rodney Harrison & Robin Torrence (eds.), Unpacking the Collection: One World Archaeology. New York: Springer, 55–82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8222-3_3.

Hartigan, John Jr. 2017: Care of the Species: Races of Corn and the Science of Plant Biodiversity. St. Paul: University of Minnesota Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1pwt718.

Hermannstädter, Anita 2019: Kunst/Natur: Interventionen im Naturkundemuseum Berlin. Berlin: Edition Braus.

IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature 2015: 2014 Annual Report of the Species Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme, https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2015-024.pdf.

Kalshoven, Petra Tjitske 2018: Gestures of Taxidermy: Morphological Approximation as Interspecies Affinity. American Ethnologist 45(1): 34–47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12597.

Karberg, Sascha 2018: Neue Pläne für das Berliner Naturkundemuseum: Über die Zukunft der Welt reden. Interview mit Johannes Vogel. Der Tagesspiegel January 23, 2018.

Kirsch, Stuart 2006: History and the Birds of Paradise: Surprising Connection from New Guinea. Penn Museum Expedition Magazine 48(1): 15–21.

Klein, Gabriele 2015: Choreographischer Baukasten. Bielefeld: Transcript. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839431863.

Klien, Michael, Steve Valk & Jeffrey Gormley 2008: Book of Recommendations: Choreography as an Aesthetics of Change. Limerick: Daghda Dance Company.

Manning, Erin 2013: Always More Than One: Individuation’s Dance. Durham: Duke University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822395829.

Myers, Natasha 2017: Becoming Sensor in Sentient Worlds: A More-than-natural History of a Black Oak Savannah. In: Gretchen Bakke & Marina Perterson (eds.), Between Matter and Method: Encounters in Anthropology and Art. London, Oxford & New York: Bloomsbury Press, 73–96.

Ness, Sally Ann 2016: Body, Movement, and Culture Kinesthetic and Visual Symbolism in a Philippine Community. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Patchett, Merle 2011: Fashioning Feathers: Dead Birds, Millinery Crafts and the Plumage Trade, https://fashioningfeathers.info (accessed May 2, 2018).

Patchett, Merle 2016: The Taxidermist’s Apprentice: Stitching Together the Past and Present of a Craft Practice. Cultural Geographies 23: 401–419. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474015612730.

Peiken, Matt 2007: Tino Sehgal Creates Experiences through Expression, https://walkerart.org/magazine/tino-sehgal-creates-experiences (accessed August 21, 2019).

Penna, Anthony N. 1998: Nature’s Bounty: Historical and Modern Environmental Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Poliquin, Rachel 2012: The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park, PA: Penn State Press.

Rose, Deborah Bird 2009: Introduction: Writing in the Anthropocene. Australian Humanities Review 49: 87. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22459/AHR.47.2009.08.

Schmitt, Susanne 2012: Ein Wissenschaftsmuseum geht unter die Haut: Sensorische Ethnographie des Deutschen Hygiene-Museums. Bielefeld: Transcript. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839420195.

Sear, Martha 2005: Rohu, Ada Jane (1848–1928). Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rohu-ada-jane-13285/text7283 (published first in hard copy 2005, accessed online May 17, 2018).

Shropshire, Steven 2015: Dance and the Museum: Curating the Contemporary (Part 1 of 3), https://stephenshropshire.com/2015/03/06/dance-and-the-museum-curating-the-contemporary-part-1-of-3/ (accessed August 19, 2019).

Tsing, Anna 2012: Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species. Environmental Humanities 1: 141–154. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3610012.

Urbino, Madame L.B., Henry Day et al. 1864: Art Recreation Being a Complete Guide: With a Valuable Receipts for Preparing Materials. Boston: J.E. Tilton.

van Dooren, Thom 2014: Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction. New York: Columbia University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231166188.001.0001.

van Dooren Thom, Deborah Bird Rose & Matthew Chrulew 2017: Introduction: Telling Extinction Stories. In: Thom van Dooren, Deborah Bird Rose & Matthew Chrulew 2017: Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations. New York: Columbia University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7312/van-17880.

van Dooren, Thom, Eben Kirksey & Ursula Münster 2016: Multispecies Studies Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness. Environmental Humanities 8(1): 1–23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527695.

Susanne Schmitt is a cultural anthropologist and sensory ethnographer (Ph.D., University of Munich), interdisciplinary artist, and facilitator (www.susanneschmitt.org). Her work focuses on creative collaborations within and beyond the label of “art meets science”. She has been managing director for a variety of interdisciplinary research networks on the topics of gender, care, and digitization and is focusing on art-based methods for organizational development and interdisciplinary facilitation.