Preliminary Remark: Why should Cultural Anthropologists Reflect on Birdhouses?

The authors started an investigation into birdhouses in the summer of 2016. This subject was initiated by a quite ordinary everyday life situation, greeting a neighbour in the garden and having a little conversation over the garden fence. The situation and the conversation were about birds, to be more precise parakeets.

There has been an increasing number of green ring-necked parakeets in the Rhineland in Germany for several years. There are different narratives about their appearance: perhaps private owners set them free or perhaps they escaped out of a zoo. The fact is that the first individuals of these exotic birds from Asia and Africa were detected in Cologne in 1967 and they spread quickly throughout the urbanized areas in the Rhineland. They found fairly good living conditions there: big old trees in parks and churchyards, a bland climate, no enemies and enough food (Hofsähs 2012). One population of about 400 birds lives in the north of the city of Bonn. They are frequently flocking in small groups in gardens in a certain quarter, picking up seeds and nuts from the birdfeeders. The scientific discourse about invasive species, changing biospheres and ecological behaviour (Braun 2004) influences the routines of everyday life exactly here, at the birdfeeders and birdhouses in private gardens – the garden practices. One afternoon, the neighbour mentioned above tried to chase three of the parakeets from the top of a tree with a broom. When he noticed the audience in the garden next to his, he came to the fence and started explaining his perhaps a little strange behaviour, by blaming the birds still sitting in the tree: “Those nasty parakeets, they always steal the food from our birdhouse. They just don’t belong here.”

This conversation was enlightening for us as cultural anthropologists. It shows how the cultural system of the binary opposite nature and culture, and othering in everyday life practices, actually works. It is quite easy to see the construction of the potential “dangerous stranger” in this argument, the suspect of all kinds of crimes. In this argument, the birds became representations of a cultural order of space and identity, an idea of “we” and “here” as opposed to “they” and “there”. It is a concept of continuity of a closed space, linked to a spatial identity of “European”, “German”, regional or local. Heterogeneous items express this spatial identity: objects and practices, language and habits, images and symbols; it is negotiated in material as well as immaterial culture.

Once fascinated by this subject of bird feeding, we started our investigation by collecting pictures of birdhouses and birdfeeders, and talking with people about their practice of feeding birds. We found more and more arguments that bird feeders and nest boxes in the garden or on the balcony are not just a cute issue or decorative architectural elements in gardens (Hänel & Vorwig 2018). In fact, they are materializations of cultural orders in a sensitive frame surrounding the house, between inside and outside, culture and nature. They represent ideas of “good” gardening, of ecological behaviour and safeguarding nature. They can be used for ecological education and, by observing the birds, expanding our knowledge about local nature.

Cultural anthropologist Friedemann Schmoll pointed out how bird protection became the initiating idea of the nature conversation movement in the nineteenth century and how oscine birds represented bourgeois values and ethics (Schmoll 1999). These ties are associative. From an observation of the behaviour of birds through the glasses of bourgeoise culture, the oscine birds act quite suitably. Beginning with the scenes of courtship when male birds try to impress the females by singing and offering food and a nest, the thorough building of the nest, to the breeding and suffering of the young birds – all this behaviour is compared with commendable family care. The brooding care of the male and the female bird together leads to the imagination of birds as monogamous living animals. In addition, their eating behaviour, picking seed by seed, fits the bourgeois ideals of good manners. The birds are clean, because they like bathing; they stay mostly in the same district, so they are seen as faithful. All this behaviour could be observed especially well in urban gardens by feeding the birds. Therefore, feeding the birds became popular in well-educated bourgeoise families in the growing cities, while the natural surroundings for birds were increasingly devastated by the progression of industrialization, urbanization and modernity.

This alliance can be found through “thick description” of the material and immaterial aspects of feeding birds. Therefore, birdhouses are material signs of concepts of co-spacing and sharing space with other species and of exclusion and distinction. Consequently, birdhouses are expressions of lifestyle, ecology and special concepts of nature, all mixed up with bourgeois ethics of behaving, interacting, food habits, concepts of gender, and, with aesthetic and moral ideas of good housing and dwelling. The performances, objects and narratives linked with the practice of bird feeding are also expressions of the deep structure of a binary system of nature and culture as an important underlying order in the culture of everyday life. This aspect became the leading perspective that this article follows: If this binary opposite of nature and culture is such a basic order of everyday life, how is this structure represented in a museum trying to exhibit and explain this everyday culture?

With this perspective in mind, we started looking at birdhouses and their functions in one of the largest open-air museums in Germany, the LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern (Kommern Open-air Museum; Faber 2009). We found two different types of birdhouses and concepts of bird protection in the museum, which we will discuss: birdhouses in the context of a nature education programme and a birdhouse from the 1960s placed in a new exhibition ensemble as a key object to reflect on the historic change of concepts of nature–culture relationships and the challenge for a multispecies ethnography in open-air museums. We are going to relate concepts of the open-air museum, focusing on the symbolic values of material culture (König 2003; Mohrmann 2006) with a perspective on human–animal relationships. The aim is to discuss open-air museums as multispecies spaces with an ethnographic approach. We point out elements of a specific nature–culture relationship staged in the material culture of the museum and its narrative. In fact, concentrating on human–animal relationships contains an anthropocentric perspective, as Kirksey and Helmreich point out, but we try to dissolve this by understanding the museum as a “contact zone(s) where lines separating nature from culture have broken down” (Kirksey & Helmreich 2010: 546) or, at least, have been challenged to be reflected.

The museum’s educational service has offered several special programmes over the years for children to build nesting boxes for bats and wild birds – especially cave-breeding birds, such as woodpeckers, nuthatches and owls – that have been placed in the museum woods (see figure 1).

Meadows with fruit-bearing trees and hedges are created as historical surroundings. They are important habitats for many different wild animals, especially small rodents, insects and birds. There is a long tradition of combining museal education about former everyday culture with nature education, such as special guided tours with the museum’s forest ranger through the woods, or women with special knowledge about traditional herbal lore, explaining the uses of wild herbs and traditional garden plants for medicinal purposes and as food.

Space in the museum, especially the outdoor area, is organized and created as “natural”. The aim is to attract wild animals, especially the endangered species. The cultural heritage seems closely connected to a corresponding heritage of nature in space and time. Therefore, the open-air museum became an important agent of ideas about preserving nature. This agency depends on contemporary concepts of nature, seen as endangered living space also for endangered creatures and plants. In fact, the museum as a “cultural institution” (Kosut 2016) brings a special “concept of nature to reality”, thus, the open-air museum is a “naturalcultural borderland” (Kirksey & Helmreich 2010: 548), a space shared by multiple species.

“Naturalcultural Borderland”: Borders and Contact Zones in the Open-air Museum

Although the open-air museum is, in fact, a multispecies shared space, there are borders dividing spheres of culture and nature, as the museum is conceptually based on a culture–nature dichotomy. The visual borders are the signs of human activities structuring the landscape: building houses, setting fences, constructing a system of paths and small streets through the outdoor area. Nevertheless, those visual borders between nature and culture are violated from both sides: especially at night, wild animals walk out of the woods over the paths, sometimes into the gardens, attracted by plants such as salad or potatoes. Moreover, some animals have their habitats in the cultural sphere of a farmhouse, for example, the common furniture beetle or the common European house spider. However, they are invisible most of the time; if they are not, they are killed or pushed out. On the other hand, people work in the woods for their economical use, for controlling the nesting boxes, biologists count and investigate plants and animals, museum employees use shortcuts outside the paths on their way through the museum. The nature in the museum is highly determined, monitored and created by humans.

There are also borders between culture and nature that can be understood as invisible. Those borders are connected mostly with human activities – practiced outside the museum, and forbidden inside because of its character as a space of nature. The driving of vehicles by visitors is forbidden, also letting dogs run free, picnicking outside the dedicated picnic areas and leaving rubbish outside the lidded rubbish bins. Preserving nature and the idea of sharing it with other species are the arguments for all these restrictions, which are accepted most of the time. Again, those borders represent a concept of nature as worthy and endangered; nature is something distinct from everyday life, a space for different experiences. This concept is underlined by a binary structure of nature and culture as distinct spheres. Consequently, this binary structure is enriched with moral attitude: conserving nature is “good” behaviour, spreading rubbish in the woods is bad and will be sanctioned.

Those borders between nature and culture work quite well, until the wasp starts to attack the visitor’s plum cake in the garden of the museum café. This situation builds a kind of sudden contact zone where the unconscious binary structure with concepts of useful and “good animals” and “bad pests” like the wasp comes into effect. However, there are also other contact zones created systematically to manage contact between culture and nature.

There are several breeding boxes placed in the woods in Kommern (see figure 1). They are typically specified for different kinds of birds and bats, in size, structure, material and placement. None of them looks like a typical birdhouse sold in supermarkets or at Christmas markets, like the ones in figure 2. Those popular birdhouses in bright colours and “funny” shapes tell more about human concepts of housing and their individual living manners than about a proper relationship to oscine birds. Perhaps they also tell something about the tolerance of birds: lacking natural holes or dead trees, they take a chance of breeding in those garden birdhouses, perhaps better than nothing. The museum birdhouses are more functional as breeding boxes (figure 1), and not decorative, apart from a very special one (see figure 3).

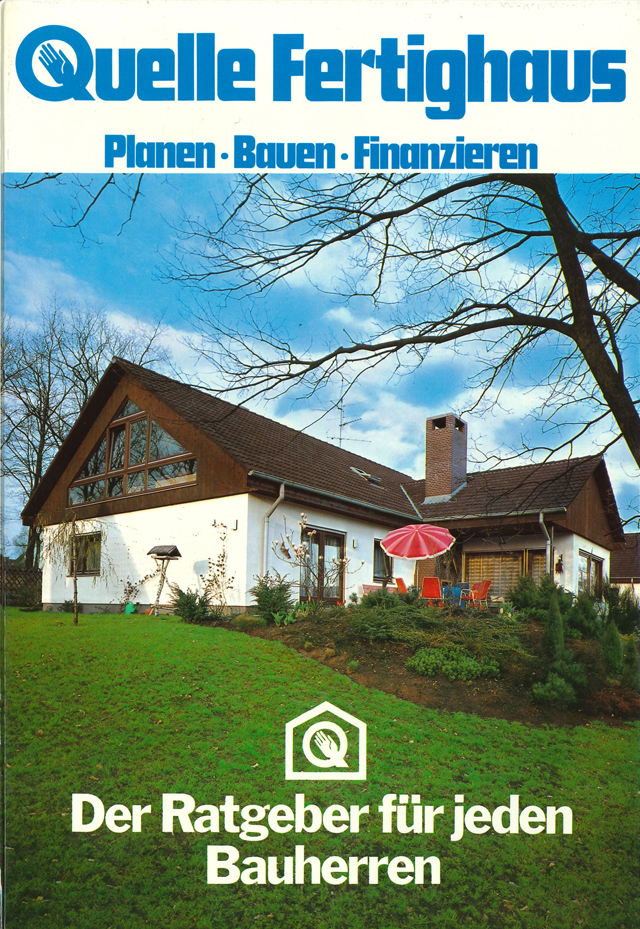

This birdhouse belongs to the so-called Quelle-Fertighaus, an original prefabricated house in the 1960s, sold by a large German mail order company. This house was translocated in toto from its original place into the museum and is now part of the new exhibition unit Marktplatz Rheinland, a development of the open-air museum showing the history of the latter part of the twentieth century (Vorwig 2015).

The exhibition unit Marktplatz Rheinland is still under construction. The aim is to represent the development of the region beginning after World War II and ending in contemporary times. The Marktplatz is constructed as a former village, developing into a small town, thereby showing the change from a rural to an urban area: the disappearance of agricultural imprinting, the rise of urbanized attendance, and the technical development and modernization. The first houses are rebuilt; they represent the change of building materials, the planning of spatial order in the houses and the family’s inventory. This massive change is also expressed in different gardening concepts.

One of the houses in this exhibition unit is named Quelle-Fertighaus. Next to this is a “residence garden”. It represents the change in everyday life from a preindustrial agricultural way of life, with large gardens full of fruit trees, potatoes and vegetables for subsistence, to a yard only with flowers (exotic) hedges and trees. This kind of garden is not designed for food production but for leisure time and recreation.

The garden was rebuilt after the first construction sketches the original owner made in 1963 and from interviews with his neighbours, who remembered the plants and the garden architecture (Herborg & Vorwig 2015). The remains of the original birdhouse were found in the cellar of the Quelle-Fertighaus before it was translocated. Old photographs of family life in the 1960s show the birdhouse in the garden as well as family activities of this time in the Rhineland (see figure 4).

This birdfeeder built as a miniature house is the first birdhouse erected in the museum. It is part of the exhibition, giving an impressive insight into concepts of housing in the 1960s. The Quelle-Fertighaus-Fibel: Vom glücklichen Wohnen (The Quelle prefabricated house reader: On happy dwelling), published originally in 1962, not only provides information and advertising, but creates a picture of modern housing, a normative image of what a house should look like (Thörmer 2015). All the pictures in this catalogue show modern, tidy and cosy furnishings and equipment with happy people living in harmony. The gender roles are pictured as the mainstream of that time.

A manufacturer catalogue from the late 1960s illustrates an impression of this new kind of housing on its front page (see figure 5). In addition, a birdhouse is part of the outdoor furniture, in a similar way as the “Hollywood swing” and a well-groomed lawn.

The birdhouse also represents a new category of relating to nature. This emotional and protectionist attitude towards nature had spread widely throughout society since the beginning of the nature conservation movement in the nineteenth century (Schmoll 2001) that focused first on the saving of local oscine birds. This attitude is quite different from the functional perspective of useful nature in the preindustrial agriculture society. The feeding and housing of birds have become quite popular activities since the beginning of the twentieth century, firstly, in urban contexts and, after the end of World War II, also in rural regions (Schmoll 2001). There is a connection between the increasing number of birdhouses and the “boom” of building houses in the 1950s and 1960s: living space was scarce after the destruction during the war and the mass migration from the East (Hänel & Vorwig 2017). Cities and villages grew; building new houses was more important than preserving nature. Wild species disappeared with the shrinking natural areas. It became increasingly necessary to feed the oscine birds, especially during the winter. At this time, feeding birds became popular, and observing the oscine birds was part of education; the presence of tits and robins in their gardens made people sure they lived their dream of living close to nature, as the images of sales promotions promised (Kaschuba 2007).

The birdhouse in the garden of the Quelle-Fertighaus in the open-air museum in Kommern is an ambiguous object. On the one hand, it is an object with authentic history belonging to the idea of housing in the 1960s. Just like other objects in the house, for example, the decoration of the dining room, the lemon-squeezer in the kitchen or the television in the living room, it represents the lifestyle and the everyday life culture of this time and the people who lived that life. The relationship to nature and the specific definition of nature at this time is part of the cultural context, it underlies the cultural order and determines thinking and acting in everyday life. In this interpretation, the birdhouse becomes a symbolic value representing fundamental cultural structures, such as the binary system of culture and nature.

What about its authentic function, feeding oscine birds with seeds in the winter? Would this be necessary and appropriate in surroundings where there is actually enough food for birds because of the large woods and a kind of preindustrial natural surrounding created by museal staging? A break in the actual museal imagination of nature arises with the birdhouse and the involved practice of feeding birds. A new concept of nature appears based on bourgeoise nineteenth-century ideas of romantic nature, developed functionally and aesthetically in the twentieth century.

The Birdhouse – a Challenge for the Museum?

The decision to continue the museum’s narrative from the nineteenth into the twentieth century represented in the new exhibition section Marktplatz Rheinland has consequences regarding the concept of including nature realized in the museum. The integration of a birdhouse in the garden, at first glance a harmless and cute object of everyday life culture, uncovers the difference between preindustrial and different postmodern concepts of nature. Therefore, the birdhouse can become an important object to initiate a reflection on the subject of nature–culture definitions as central to cultural systems in the narrative of the museum.

The birdhouse in front of the Quelle-Fertighaus is the first item of that kind to show the historic development of people’s relationship to birds after 1945 in this exhibition. It represents the change in everyday life from a preindustrial agricultural way of life to industrial times with mass production and no need for subsistence in one’s own garden. To feed birds in a birdhouse is a kind of luxurious pleasure that would have been unthinkable in the olden days. Most people had to save the seeds for their own survival. Bird feeding has been an increasing phenomenon in times of economic growth since the 1960s. Therefore, there will be more of these birdhouses in the gardens around the Marktplatz Rheinland in the future. The changing definitions of nature and culture and the different practices of excluding and building a hierarchy could be a new story to tell when exploring the development of our society through everyday life culture. But questioning the nature–culture binary in context of the policy of space in open-air museums may lead to an enlightening discourse on open-air museums as multispecies sites.

References

Braun, Michael 2004: Neozoen in urbanen Habitaten: Ökologie und Nischenexpansion des Halsbandsittichs (Psittacula krameri SCOPOLI, 1769) in Heidelberg [Alien species in urban habitats: Ecology and niche expansion of ring-necked parakeets (Psittacula krameri SCOPOLI, 1769) in Heidelberg]. Diplomarbeit Fachbereich Biologie Philipps-Universität Marburg, Spezielle Zoologie, https://www.uni-heidelberg.de/institute/fak14/ipmb/phazb/Thesis/Braun_2004.pdf (accessed October 25, 2018).

Faber, Michael H. 2009: LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern: Rheinisches Landesmuseum für Volkskunde. Museumsführer. Kommern: LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern.

Hänel, Dagmar & Carsten Vorwig 2017: Zwischen Aufbewahrung und Heimat: Eine Flüchtlingsunterkunft und ihre Musealisierung. Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde/Archives Suisses des Traditions Populaires 113(1): 59–78.

Hänel, Dagmar & Carsten Vorwig 2018: Good Birds, Bad Birds? Überlegungen zu Mensch-Tier-Beziehungen im Garten. Alltag im Rheinland, 48–65.

Herborg, Ute & Carsten Vorwig 2015: Sonnenschirm und Bowleglas: Schöne neue Gartenwelt. In: Josef Mangold (ed.), Quelle-Fertighaus: Ein Haus aus dem Katalog. Reihe zum Marktplatz Rheinland: 2. Kommern: LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern, 60–67.

Hofsähs, Ulrike 2012: Papageien machen sich im Rheinland breit. Die Welt, January 29, 2012, https://www.welt.de/wissenschaft/article13828914/Papageien-machen-sich-im-Rheinland-breit.html (accessed October 25, 2018).

Kaschuba, Wolfgang 2007: Das Einfamilienhaus: Zwischen Traum und Trauma. Archithese 37: 18–21.

Kirksey, Eben & Stefan Helmreich 2010: The Emergence of Multispecies Ethnography. Cultural Anthropology 25: 545–576. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01069.x.

König, Gudrun M. 2003: Auf dem Rücken der Dinge: Materielle Kultur und Kulturwissenschaft. In: Kaspar Maase & Bernd Jürgen Warneken (eds.), Unterwelten der Kultur: Themen und Theorien der volkskundlichen Kulturwissenschaft. Köln: Böhlau, 95–118.

Kosut, Mary 2016: Nature in the Museum. In: Renee C. Hoogland (ed.), Gender: Nature. London: MacMillan, 283–296.

Mohrmann, Ruth E. 2006: Können Dinge sprechen? Rheinisch-westfälische Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 56: 9–24.

Schmoll, Friedemann 1999: Vogelleichen auf Frauenköpfen: Zur symbolischen Organisation von Naturbeziehungen in modernen Gesellschaften. Rheinisch-westfälische Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 44: 155–169.

Schmoll, Friedemann 2001: Kulinarische Moral, Vogelliebe und Naturbewahrung: Zur kulturellen Organisation von Naturbeziehungen in der Moderne. In: Rolf-Wilhelm Brednich, Annette Schneider & Ute Werner (eds.), Natur – Kultur: Volkskundliche Perspektiven auf Mensch und Umwelt. 32. Kongreß der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde in Halle, from September 27 to October 1, 1999. Münster (et al.): Waxmann, 213–227.

Thörmer, Raphael 2015: Vom glücklichen Wohnen: Die Quelle-Fertighaus-Fibel. In: Josef Mangold (ed.), Quelle-Fertighaus: Ein Haus aus dem Katalog. Reihe zum Marktplatz Rheinland: 2. Kommern: LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern, 74–79.

Vorwig, Carsten 2015: Die Moderne im Dorf: Konzeptionelle Grundlagen für den Marktplatz Rheinland. In: Josef Mangold (ed.), Moderne Zeiten: Der Marktplatz entsteht. Reihe zum Marktplatz Rheinland: 1. Kommern: LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern, 20–29.

Dagmar Hänel, Ph.D. in European ethnology/cultural anthropology. She has been a research fellow at the Department of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Bonn and head of the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the LVR-Institute of Regional Studies. Since 2018 she is the Director of the LVR-Institute for Regional Studies. Her research interests are ritual studies, visual anthropology, studies in religious culture and everyday culture.

Carsten Vorwig, Ph.D. in European ethnology/cultural anthropology. Since 2003 he is head of the Department of Historic Architecture at the LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern – Rheinisches Landesmuseum für Volkskunde. His research interests are historic architecture and house research, visual anthropology, studies in everyday commodities and everyday culture in the eighteenth to twenty-first century.