A wolf stands in the middle of the exhibition room. Although the animal’s size is quite intimidating, and the mouth is slightly open, showing its sharp teeth, it looks strangely kind. Facing the showcase that surrounds the animal stands a long-haired girl, probably around six years old. Fascinated by the animal, she comes as close to the showcase as possible, seeming to want to touch the stuffed and musealized animal before her. On the one hand, this incidentally observed performance embodies a reinterpretation of the story of the girl and the wolf that goes beyond the popular version of the Grimm brothers. In a manner exemplified by the intrepid little girl standing in front of the showcase, this new version is told in numerous new books addressed to children and young adults: A tough girl is not afraid of yesterday’s monsters, she is instead curious and open to new challenges, enjoys meeting a wolf, or even a wolf pack.1 On the other hand, the scene in the exhibition room associates the fact that people today also still seem susceptible to “Little Red Riding Hood syndrome”, as they are faced with news about wolves coming close to kindergartens in urban settings.2

As the writer, scholar and artist Rachel Poliquin argues, all taxidermy is an orchestration (Poliquin 2008). By preparing the dead body of the animal in a certain manner, the taxidermist tells his or her story, and viewers may add still more interpretations. On this afternoon in the museum in Bad Windsheim, Germany, the stuffed wolf is most often interpreted as an invitation to come closer. Under the heading “Who is afraid of the big bad wolf?”, the museum introduces visitors to the history of the relationship between wolves and humans. Visitors are asked to reflect on this relationship that is still highly complex, ambivalent and full of tensions. At the end of the exhibition the curators ask, “What do you think about the return of the wolves?”, and the museum guestbook reflects a plurality of opinions about the presence of wolves in today’s European societies.

Museums are complex places of learning, exchange and experience. In the context of the current rapid transformations in the world, the roles of museums are being rethought, resulting in museums’ engagement in discussing current questions and challenges of human societies (Odding 2011; Eggmann & Kuhn 2017). Museums are increasingly expected to act as “contact zones” (Clifford 1997), providing a social space for meetings, dialogues and negotiations. They are asked to produce counter-images to common stereotypes and address multiperspectivities (Johansson 2014; Hooper-Greenhill [2000]2005), so that they can become sites for rearticulations and change. At the same time, they are encouraged to take up activist approaches in order to make a difference in the world. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, museum and heritage scholar, pointed this out insistently when she encouraged museums to be “agents of transformation”.3 Hand in hand with this goes the postulation that museums should become participative museums actively engaging people as cultural participants and not as passive consumers, and co-creating exhibits and collections with individuals and communities (e.g. Simon 2010; Gesser et al. 2012). At the beginning of the twenty-first century, in times of ecological crisis and climate change, and in a world of a dramatic loss of species, how can museums be agents of change in terms of informing about human–animal coexistence? How can living together with other-than-humans – be they sheep and cows or wolves, beavers, bears and lynxes – be part of exhibition narratives for the future? What are our responsibilities toward these so-called wild-life “returners”? Can they themselves become co-creators of participatory museums?

These are some of the questions discussed in museums today in the framework of the (new) roles of the museum described above. However, it is a challenge for curators to find ways of representing these urgent questions and debates. How does one narrate the plurality of human–animal relationships? Since their so-called return, wolves have provoked severe debates in European societies and, therefore, various museums, from natural history museums to cultural history museums and others, have dealt with this topic in their exhibitions.4 Although each institution follows its own questions, we can observe a general tendency. Influenced by the work of Bruno Latour (1993), Donna Haraway (2008) and others from the fields of science and technology and philosophical feminist studies, museums strive to gradually overcome the modern divide between nature and culture. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, museums are increasingly becoming places where “naturecultures”, as a heuristic “space of reflection” (Gesing et al. 2019: 10), are explored and multispecies worlds are reflected upon. This special issue of Ethnologia Europeaea aims to probe the potentials of the multispecies museum by exploring innovative approaches of analyzing the co-presence of animals, plants and humans in exhibits of various kinds.

Following Liv Emma Thorsen’s argument (2018), animals, like other living beings, have been part of cultural history museums since their beginnings. What is new today is another framing of the topic. Animals or plants are no longer dealt with as objects of human cultures, instead, they are framed as active agents themselves. Exhibitors increasingly focus on the question of understanding humans within the entanglement of life. The current exhibition “Plants and Humans” in Deutsches Hygiene-Museum in Dresden, Germany, is one example of this new framing. The curators of the exhibition reflect the modern hierarchy of plants within their living environment; they aim to show “that humans are living beings in between others” and that humans are “inseparably woven into mutual dependence” (Meyer & Weiss 2019: 105). Recently developed museum concepts, such as that of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, the Biotopia Museum of Natural History in Munich or the museum of microbes Micropia in Amsterdam, reflect humans as parts of ecosystems in different sociobiological milieus (see Rehwagen 2017). A specific method that facilitates an experience of the entanglements of life, invites discussion, and generates new perspectives and collaborations, are walking seminars through rural as well as urban landscapes, enticing embodied research (Shepherd, Ernsten & Visser 2018). In 2018, such a walking seminar through a zoological landscape was convened at Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo, one of the earliest museums in Amsterdam, with the intention of employing the zoo as a space of reflection and imagining the zoo’s (alternative) futures.6

These new perspectives in the museum world are part of a broader metamorphosis in both science and society, where hybrid spaces of naturecultures have become increasingly highlighted. The conceptualization of animals, plants, microbes and other living beings as “other-than-humans” and as effective parts within our “multispecies societies” (see Fenske 2019: 177) is at the center of attention within the research field of multispecies studies (also called multispecies ethnography or anthropology beyond the human). In this field, humans and other species all form part of the “entanglement of life”. Multispecies scholars ask “how human lives, lifeways, and accountabilities are folded into these entanglements” (van Dooren, Kirksey & Münster 2016: 1; see also Kirskey & Helmreich 2010). Approaches such as the notion of agential realism in the context of new materialism proposed by physicist, feminist theorist and philosopher Karen Barad reflect once more the potentials of materialities as effective agents (2015). Agential realism, Barad maintains, depicts the becoming of all living materialities through their specific multispecies entanglements.

Awareness of the strong interwovenness of nature and culture is gaining more and more attention in society and politics. At the same time, however, (European) nature policies face serious challenges, due to a lack of public debate and participatory policy-making. Scholars elaborating our understanding of nature–society relations like Matthijs Schouten, Wilhelm Schmid and Annemarie Mol, have called for more dialogue. Diverse knowledge repertoires of natureculture (e.g. ecological, anthropological, knowledge of farmers, walkers, artists), they argue, need to be taken into account (Mommaas, Dammers & Muilwijk 2017).

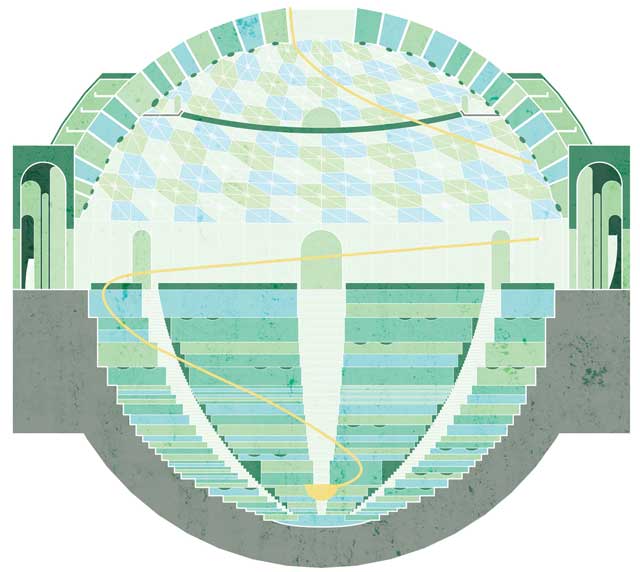

One of the initiatives to raise awareness of natureculture relations in society and, consequently, of developing a governance for both humans and other-than-humans is the Dutch art and science project “Parliament of Things”, which was founded in 2015, and received much media attention. Based on Latour (1993), a democratic space is organized where, amongst many others, “bacteria, squirrels, lakes, people and ferns come together to jointly make decisions” (Slob 2017: 22). Together with architect Lorna Gibson and artist Aldo Brinkhoff, the creators of the project, Thijs Middeldorp and Joost Janmaat, have designed a building for the parliament (see figure 1). Symbolizing the Earth, it is a monument of emancipation of nonhuman life, facilitating in its inside communication and debate without hierarchy between “entities with different languages, various ideas of time and existing on different scales” (Middeldorp & Janmaat 2017: 9). The visionary architecture and imaginative environment of “a politics beyond men” (ibid.: 3) stimulate a perception of the world as a shared space.

The project of the Parliament of Things encourages people to put themselves in the position of other-than-humans, for instance, by writing a diary of a specific animal or a plea stating its interests. However, specific challenges are bound to appear: How can one put oneself in the position of an animal?7 How can one represent the view of an animal if one is only able to use human language and human formats? How can one weigh interests and deal with the fact that one might lose the awareness of entanglements when representing a specific species? The project has recently generated the subproject Embassy of the North Sea (2018–2030), consisting of, amongst others, workshops, lectures, art performances and sensual experiences. The project calls for attention to humans and other-than-humans connected to the North Sea – from crabs, to marram grass, tourists or waves – as autonomous actors with their own identities and value systems, entangled in complex processes of production, destruction, reconstruction and change. It also includes an initiative to determine whether the North Sea might become recognized as a legal person with its own rights, following the example of the Ecuadorian constitution, which acknowledges the rights of the rainforest as an ecosystem, and New Zealand, which recognizes the Whanganui river as a legal person.

How can the Parliament of Things and the Embassy of the North Sea inspire museums and incite innovative approaches? Those projects, which decenter individual human agents and draw attention to the agency of other-than-humans, make it possible to experience complex formations of agency in a playful but not flippant way. This playfulness is an important resource to address a serious topic within the public, where people are often overstrained by reproaches of the ecological costs of their lifestyles or by moral instructions by scholars, politicians and others. The projects can inspire museums to likewise approach the topic in a playful way, conscious about its complex relationship to seriousness (cf. Shepherd 2018: 13). They can also stimulate museums to work with a system of guardians. Curators, visitors or others might become guardians of a particular animal or plant and state its interests. Or they even might stimulate museums to experiment with co-creations with other-than-humans on an equal basis. The Parliament of Things was launched in Artis, that is in the process of developing a museum on relations between humans and nature. The future will tell how projects like the Parliament of Things will be taken up by museums.

In focus of this special issue of Ethnologia Europaea are museums as learning spaces of naturecultures. The issue takes the innovative approach to analyze the becoming with of humans and other living beings in a variety of current exhibitions. We invited colleagues from different fields – artists, anthropologists, historians, researchers and museum practitioners – to investigate their research topics from a multispecies perspective. We asked for their experiences with collaborating with other-than-humans in museums. We wanted to learn something new about the challenges of narrating multispecies worlds in museums and about important historical developments, possibilities and limitations.8 The result is a special issue which supplies insights into the potentials of a multispecies perspective on museums and museums’ multispecies approaches. By analyzing the different styles museums pursue in order to highlight multispecies worlds for society, the issue also introduces new modes of exhibiting, new ways of focussing on artefacts and even new kinds of artefacts. Furthermore, the perspective on multispecies worlds offers insights into the challenges of working together with other living beings and into new ways of narrating societies.

Traditional open-air museums have a lot of experience not only concerning the narration of human and other-than-human cohabitation, but also with other-than-human actors as agents in the museum itself. This style of exhibition, often entailing the narration of a story of “how things might have been”, has encouraged many museum curators to stage rural multispecies entanglements. Today, not only the popular Swedish museum Skansen, established in 1891, but also many other open-air museums all over Europe showcase typical animals of their regions, often so-called old races of cows, chicken or horses. Gardens and sometimes also fields illustrate the variety of plants in times before their severe reduction during the twentieth century. Wiebke Reinert, in her contribution, takes as her starting point the beginning of this way of narrating or staging multispecies worlds. Through the lens of exhibition studies, she focuses on nineteenth-century zoos and open-air museums at a time when both institutions shared practices of exhibiting other-than-humans. Today, open-air museums are nice green places to relax; parents enjoy the freedom of the day pushing a baby buggy and buying food that their children can feed the museum goats. As Reinert points out, visitors in this kind of museum learn particularly through sensual experiences, through the body. What do they incorporate concerning the everyday co-living on the countryside in the preindustrial era? How can open-air museums use their special capacities of learning through the body to narrate the everyday life of humans and other-than-humans under changing conditions in time and space?

Michael Schimek and Jadon Nisly deal with these questions from a different perspective and examples from different regions in Germany. They reflect on the problems and opportunities of exhibiting historical human–animal relationships. Michael Schimek argues that although human–animal relationships are inscribed in architecture and other artefacts, visitors to the museum are usually not familiar with interpreting these materialities. Empty houses, stalls and barns and their historical equipment will not tell visitors much about the lives of their former habitants. For this reason, more and more museums include animals in order to add additional significance to the exhibition. However, keeping animals is a challenge because museums have to balance historical ways of animal husbandry with today’s ethical requirements of animal welfare. The fact that museums keep today’s descendants of formerly common races that are themselves unfamiliar with the historical living conditions of their ancestors is another challenge. Under these circumstances it is not easy to communicate how the cohabitation of humans and animals depends on not only practices and modes of rural economies or forms of agriculture but also hierarchies within the rural households. In addition to this complex situation, Schimek illustrates with different examples how animals have, nevertheless, become important tutors in today’s museums by provoking visitors to incorporate an awareness of how animals lived, worked and also suffered and still do so today under the conditions of rural economies.

Jadon Nisly discusses how, from the animals’ point of view, the time of the Enlightenment did not improve their lives. To the contrary, modernity brought along other living conditions, which probably constituted a burden for animals and humans alike. From then on, animals and humans lived together in byre-houses for the whole year and, in the name of alleged progress and financial profit, the animals no longer enjoyed their outdoor living spaces on pastures. It was also the beginning of a special relationship between dairymaids and cows, since the young women had to care for their cows. As Nisly makes clear, from a multispecies perspective, open-air museums risk sentimentalizing historical conditions of cohabitation. Like Schimek, he underlines the problem of communicating not only pleasant moments of living together but also the routinized violence and power imbalance between humans and other-than-humans. He also sees the potential that visitors to open-air museums might physically learn with their bodies and senses, by combing their fingers through the animals’ fur, smelling the dung and feeling the warmth of the animal bodies, what it means to live closely together with other-than-humans.

Dagmar Hänel and Carsten Vorwig discuss in their contribution how open-air museums profit from putting marginal artefacts into focus. Discussing the example of a collection of birdhouses of the LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern in Germany, they show how birdhouses invite visitors to reflect on the changing living conditions of humans and other-than-humans in modernity, as well as on postmodern multispecies societies.

Powerful artefacts are also the topic of Elisa Frank’s study. She deals with wolf taxidermy as a new and highly popular artefact in diverse museums. The questions of how museums integrate stuffed wolves, what kind of story about the relationship between wolves and humans the presentation of the artefacts narrates and how it interprets the return of the “wild” depend to a considerable extent on the taxidermist’s work and the effects created by the wolves’ bodies. By discussing how taxidermists work, Frank shows how they participate in the production of the narrative about the return of the wolves and of certain ideas about how to live together with them. Although they are dead and stuffed, wolves have an astonishing agency in European societies through their share in museum exhibitions.

Susanne Schmitt’s contribution shares with Frank the focus on taxidermy as a powerful practice letting museums organize special arrangements and a variety of narrations. But there is more: Schmitt invites the readers to participate in the artistic-ethnographical intervention she and her artistic colleague Laurie Young organized at the Australian Museum in Sydney. With “Send out a pulse!”, an audio walk involving extensive movement, the intervention works with bodies in motion. Similar to open-air museums, the incorporation of new experiences allows museum visitors to develop new perspectives and points of view, in this case, concerning mass extinction.

As the contributions in this special issue demonstrate, in the face of ecological crises at the beginning of the twenty-first century, pronounced by some to be the sixth mass extinction of the Earth, museums increasingly seize the chance to use their potential as pivotal places of learning, reflection, discussion and experience. By exploring the multispecies worlds, they invite human visitors to meet not only the other-than-human but also to reflect on their own position as humans within a multispecies world.

Notes

- These new versions of Little Red Riding Hood are told today in several European societies; here, we use some German versions to illustrate this development: Kristina Andres (2012): Suppe satt, es war einmal. München: Arsedition; André Bouchard (2015): Achtung, Woohoooolf! München: Knesebeck; Luisa Stenzel (2016): Wilma und Wolf. Berlin: Round not Square. [^]

- See, for example, a report in Germany’s popular daily Bild about a wolf passing close to a kindergarten in Winsen an der Aller, a small community in the region of Celle, north of Hannover, https://www.bild.de/regional/hamburg/wolf/woelfe-kommen-in-die-staedte-54704784.bild.html (accessed September 19, 2019). [^]

- Keynote Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Agents of transformation: The role of museums in a changing world, 14th SIEF Congress, Santiago de Compostela, April 17, 2019, https://www.siefhome.org/congresses/sief2019/keynotes.shtml. [^]

- To list only a few exhibitions in German-speaking countries: Landesmuseum Hannover: “Der Wolf: Ein Wildtier kehrt zurück”, May 21–October 15, 2017; BIWAK#19 Alpines Museum der Schweiz, Bern: “Der Wolf ist da: Eine Menschenausstellung”, May 13–October 1, 2017; MARKK Museum am Rothenbaum Kulturen und Künste der Welt, Hamburg: “Von Wölfen und Menschen”, April 12–October 13, 2019. [^]

- Translated from German by the authors of this contribution. [^]

- It concerned a collaboration between the Reinwardt Academy and Artis. [^]

- The organizers of the Parliament of Things have worked with a theater director to design a ritual that helps attendants to “transform” (Slob 2017: 22). [^]

- Some of the contributions in this special issue were presented and discussed in the panel “Shared Spaces: Perspectives on Animal Architecture” at the conference of the International Society for Ethnology and Folklore SIEF in Göttingen in 2017. [^]

References

Barad, Karen 2015: Verschränkungen. Berlin: Merve.

Clifford, James 1997: Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Eggmann, Sabine & Konrad J. Kuhn 2017: Das Museum als Ort kulturwissenschaftlicher Forschung und Praxis – eine Einleitung. Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde 113(2): 7–12.

Fenske, Michaela 2019: Was Karpfen mit Franken machen: Multispecies-Gesellschaften im Fokus der Europäischen Ethnologie. Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 115(2): 173–195.

Gesing, Friederike, Michi Knecht, Michael Flitner & Katrin Amelang (eds.) 2019: NaturenKulturen: Denkräume und Werkzeuge für neue politische Ökologien. Bielefeld: Transcript. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839440070.

Gesser, Susanne, Martin Handschin, Angela Janelli & Sibylle Lichtensteiger (eds.) 2012: Das partizipative Museum: Zwischen Teilhabe und User Generated Content. Neue Anforderungen an kulturhistorische Ausstellungen. Bielefeld: Transcript. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839417263.10.

Haraway, Donna J. 2008: When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean (2000)2005: Culture and Meaning in the Museum. In: Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (ed.), Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture. New York: Routledge, 1–22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2752/174322005778054203.

Johansson, Christina 2014: The Museum in a Multicultural Setting: The Case of Malmo Museums. In: Laurence Gouriévidis (ed.), Museums and Migration: History, Memory and Politics. Abingdon & New York: Routledge, 122–137.

Kirksey, S. Eben & Stefan Helmreich 2010: The Emergence of Multispecies Ethnography. Cultural Anthropology 25(4): 545–576. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01069.x.

Latour, Bruno 1993: We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Meyer, Kathrin & Judith Elisabeth Weiss 2019: Von Pflanzen und Menschen: Über ein ungleiches Verhältnis. In: Kathrin Meyer & Judith Elisabeth Weiss (eds.), Von Pflanzen und Menschen: Leben auf dem grünen Planeten. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 10–13.

Middeldorp, Thijs & Joost Janmaat 2017: Parliament of Things: Democracy in the Anthropocene. Amsterdam: Program book Holland Festival 2017.

Mommaas, Hans, Ed Dammers & Hanneke Muilwijk 2017: The Interwovenness of Nature and Culture. In: Hans Mommaas, Bruno Latour, Roger Scruton, Wilhelm Schmid, Annemarie Mol, Matthijs Schouten, Ed Dammers, Marian Slob & Hanneke Muilwij, Nature in Modern Society: Now and in the Future. The Hague: PBI. Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 10–21.

Odding, Arnoud 2011: Het disruptieve museum. The Hague: www.odd.nl.

Poliquin, Rache 2008: The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press.

Rehwagen, Ulrike 2017: Bio – Biotop – Biotopia: Ein Museum des Lebens. Aviso 4: 42–45.

Shepherd, Nick 2018: Escaping from the “White Cube” of the Seminar Room. In: Nick Shepherd, Christian Ernsten & Dirk-Jan Visser (eds.), The Walking Seminar: Embodied Research in Emergent Anthropocene Landscapes. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University of the Arts, 12–13.

Shepherd, Nick, Christian Ernsten & Dirk-Jan Visser (eds.) 2018: The Walking Seminar: Embodied Research in Emergent Anthropocene Landscapes. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University of the Arts.

Simon, Nina 2010: The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.

Slob, Marjan 2017: Facilitating the Parliament of Things. In: Hans Mommaas, Bruno Latour, Roger Scruton, Wilhelm Schmid, Annemarie Mol, Matthijs Schouten, Ed Dammers, Marian Slob & Hanneke Muilwij, Nature in Modern Society: Now and in the Future. The Hague: PBI. Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 22–23.

Thorsen, Liv Emma 2018: Animal Matter in Museums. In: Hilda Kean & Philip Howell (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Animal-Human History. London: Routledge, 171–195. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429468933-8.

van Dooren, Thom, Eben Kirksey & Ursula Münster 2016: Multispecies Studies: Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness. Environmental Humanities 8(1): 1–23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527695.

Michaela Fenske holds the chair of European ethnology/folklore at the University of Würzburg. Her research fields include rural studies, economic anthropology, historical anthropology, anthropology of writing and multispecies studies. Currently she is pursuing a research project studying the effects of the return of wolves to Germany. Since 2018, she is a member of the working group on Biodiversity of the Leopoldina, German National Academy of Sciences.

(michaela.fenske@uni-wuerzburg.de)

Sophie Elpers (Ph.D., University of Amsterdam) is a researcher in European ethnology at the Meertens Institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam. Her research focuses on material everyday cultures and specifically everyday architectures in rural areas. She also works for the Dutch Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage/Dutch Open Air Museum, researching intangible heritage in museums. She is a member of the steering group of the “Intangible Cultural Heritage & Museums Project”, funded by the Creative Europe Program of the European Union.