Ethnically/Locally Rooted, Multi-culturally/Regionally Blended

Ethnologists, folklorists, and kindred scholars have long examined the changing experiences of migrants to and from Europe, often emphasizing asymmetrical relationships between newcomers and established hosts, as well as the dynamic between cultural retention and assimilation. So it was in the 1960s when the Swedish folklorist Barbro Klein conducted ethnographic research in northern Maine’s New Sweden to determine whether Swedish traditions had been sustained or diminished. Returning thirty years later, at a time when Sweden was becoming increasingly multicultural, Klein realized her prior binary interpretive frame was insufficient. Not simply an “Anglo-Nordic” site wherein minority Swedes and majority Anglo-Americans interacted, New Sweden was more accurately (re)considered as part of a diverse egalitarian community wherein “the descendants of Swedish immigrants form a culturally distinct American region… with Acadians [French Canadians], Micmac Indians, Yankees, and others” (Klein 2004: 258). Accordingly, Klein called for “future research” into “the co-existence between ethnic/local cultures” and “regional cultural blends” (Klein 2004: 258).

America’s Upper Midwest was populated similarly in the nineteenth century by shifting combinations of indigenous peoples, Anglo-Americans from New England and New York, and particularly Germanic, Irish, Nordic, and Slavic immigrants. Clustering sometimes in discrete settlements but more often comingling, especially as agrarian and industrial workers, they simultaneously sustained their respective evolving ethnic/local identities; assimilated elements imposed by larger American institutions; and forged an emergent creolized regional cultural blend by creatively fusing varied Old and New World elements into expressive folk forms (Dorson 1947: 48; Leary 2015: 1).

“The Swede from North Dakota” is one such complex ethnically/locally rooted yet regionally blended expressive form. A stanzaic narrative folksong or ballad, it has circulated in differing versions throughout the Upper Midwest – extending into the northern Great Plains, Pacific Northwest, and western Canada – for more than a century. Ubiquitous yet betwixt-and-between, thoroughly regional yet neither fully Swedish nor Anglo-American, it was either unknown to or considered too culturally ambiguous by both G. Malcolm Laws in his canonical concordance of America’s narrative folksongs, Native American Balladry (1964), and by Robert L. Wright in his survey anthology of Swedish Emigrant Ballads (1965).

This revisionist essay sketches “The Swede from North Dakota’s” folk/vernacular sources, situates and elaborates on scenes presented through its stanzas, and explicates its enduring cultural significance.

“The Swede” in Oral Tradition, Reported Events, Songbooks, and Sound Recordings

“The Swede from North Dakota” was evident in and around Minneapolis in the early 1900s and, despite ensuing geographic spread, remains rooted and best known in the Upper Midwest. Of uncertain origin, borrowing the tune of “Reuben and Rachel,” a popular ditty from the 1870s, the song has been invariably rendered in an intentionally comic broken-English mock-Scandinavian dialect dubbed “Scandihoovian” (Hall 2002: 772). Chronicling the misadventures of a Swedish immigrant itinerant laborer who is lured from rural North Dakota to Minnesota’s Twin Cities by “da big State Fair,” this folksong has been performed in many versions, and has been parodied by railroad and building trades workers, farmhands, lumberjacks, hobos, labor activists, Swedish vaudevillians, Norwegian hillbilly entertainers, Ladies Aid groups, community glee clubs, and more. In the 1970s, it entered the Scandinavian and American folksong revivals.

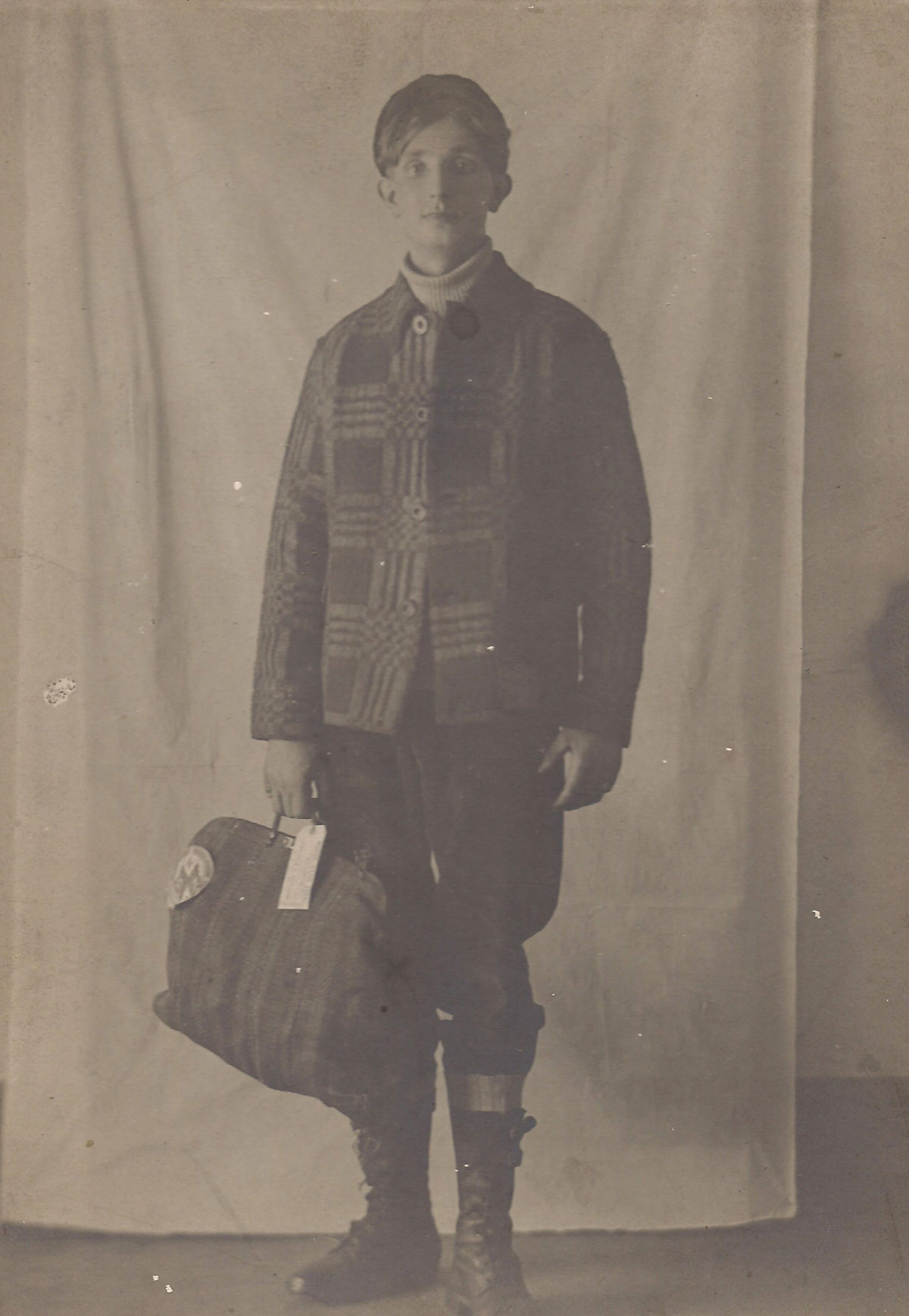

The first verifiable evidence of the song’s existence is from 1904 when Carl Bruce (1887–1980), a hotel porter in Minneapolis, acquired the song from his boss, New York born John F. Auly, then won first prize singing it at the establishment’s amateur night. Raised with an appreciation of such singing – inspired by Swedish “peasant comedians” (bondkomiker) such as Lars Bondeson – Bruce had immigrated in 1902 from Göteborg to Merrill, Wisconsin, joining his lumberjack father and toiling in a sawmill before moving to Minneapolis. Bruce resettled in Rockford, Illinois, around 1911, where he ran a machine in a furniture factory, was active in socialist circles, and entertained local Swedes in Rockford’s Svea Hall as Sven på Lappen (Sven on the Patch) – a comic stage name drawn from a distant relative, Sven Svensson, known by that nickname since he had an åkerlapp (a small field) in the province of Bohuslän (Ericson 1971; Bruce 1980; Ericson & Bruce 1982; Anonymous 2013) (see Figure 1).

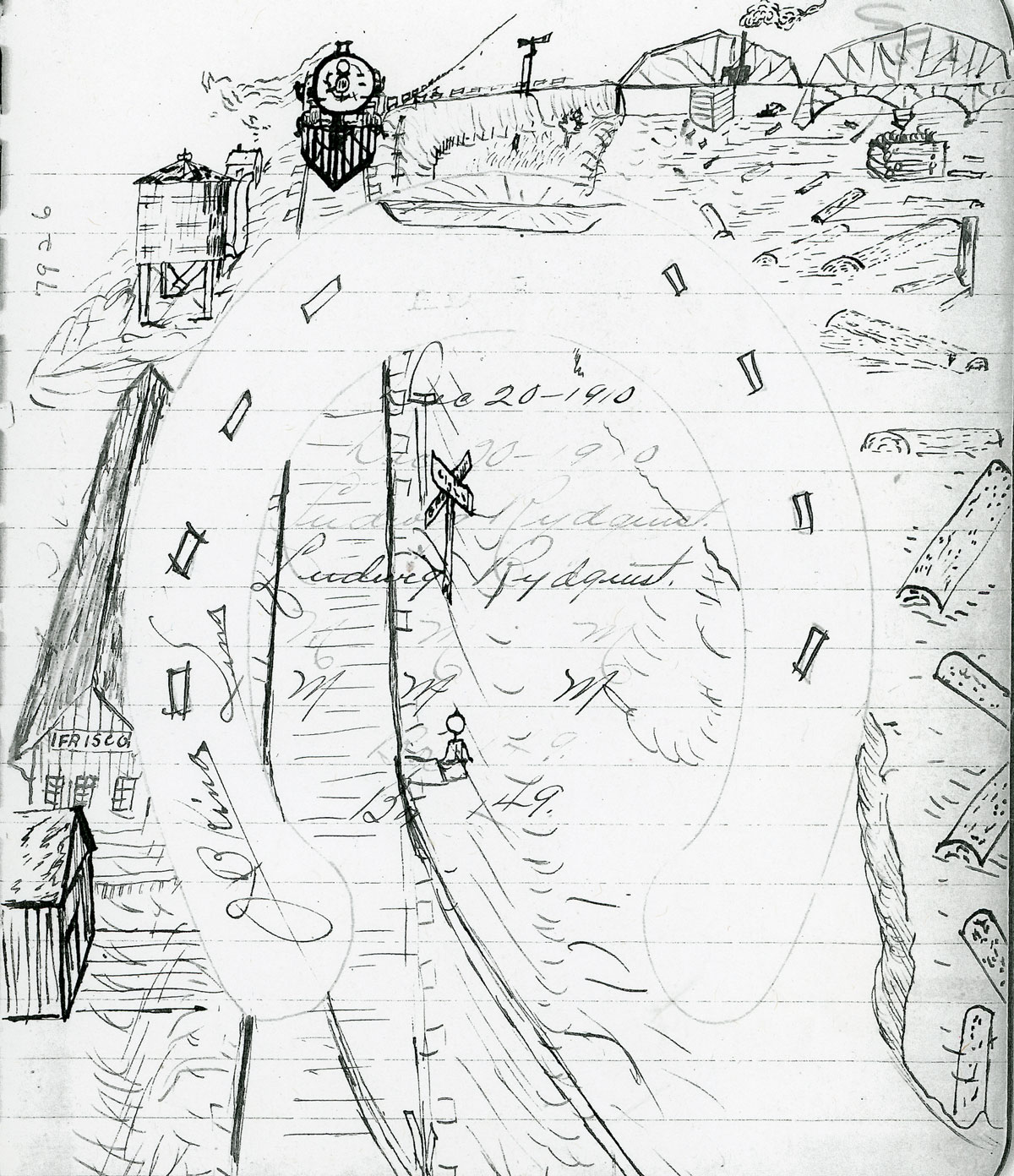

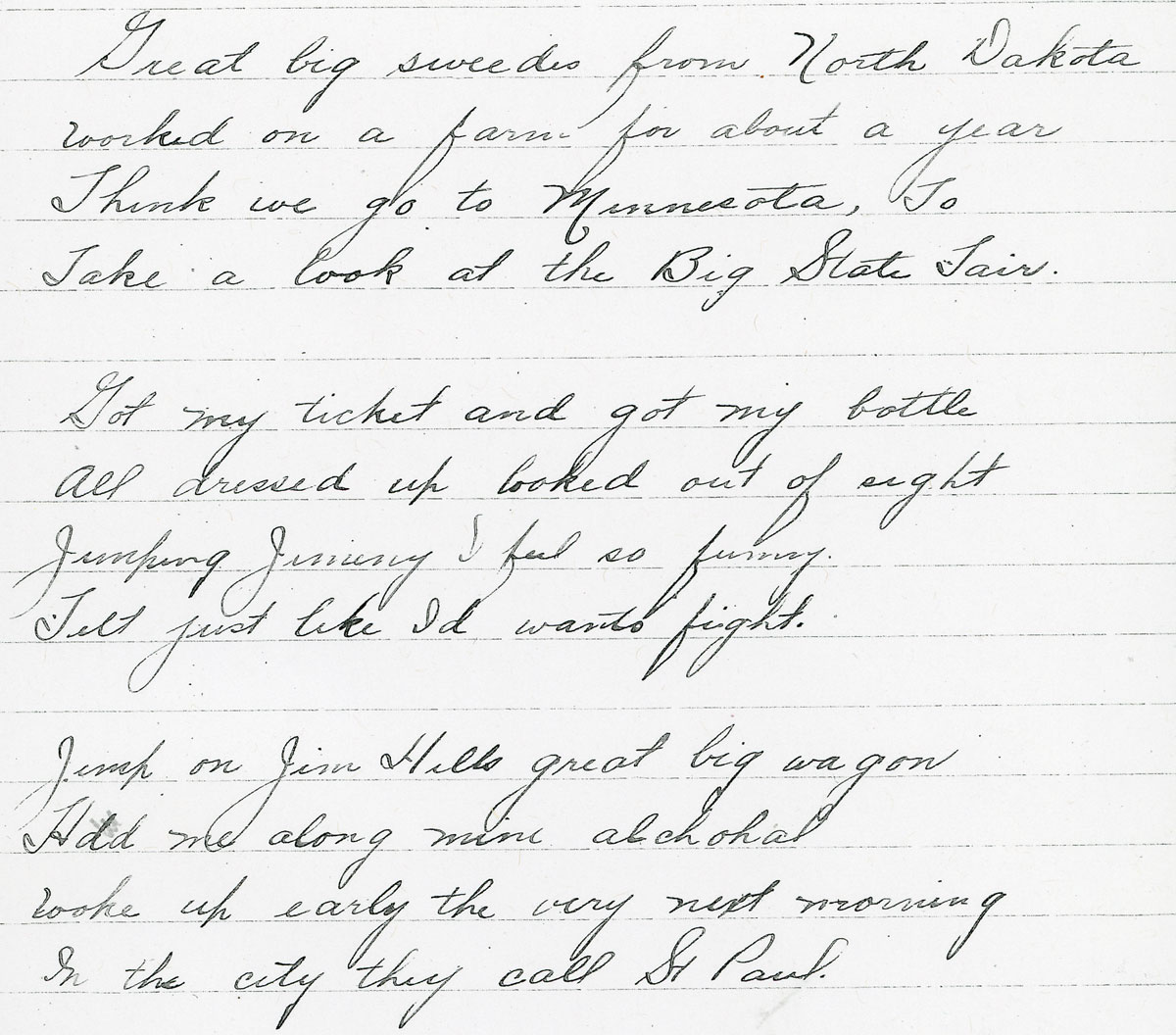

The song’s other early sources are likewise Upper Midwestern working-class Swedes. Nels Anderson (1889–1986), son of a Swedish immigrant and later a pioneering sociologist of hobos and homelessness, was a migratory railroad gang worker when he learned a version circa 1907 from a co-worker known only as “Dino, a good story teller, a man of humor… a rounder of wide experience. He had done many kinds of work, up north in summer and to the southern states in winter. Often he worked on rock moving jobs and was expert in using dynamite, hence his ‘moniker,’ dino, a rock man” (Anderson 1975: 54). In 1910 Ludwig Rydquist (1890–1956) – a railroad section gang worker born to Swedish immigrant parents in Marine on Saint Croix, Minnesota – sustained the Old World tradition of handwritten songbooks (handskrivna visböcker) by inscribing the song’s lyrics in an illustrated notebook he and his brother Oscar used in banjo-guitar duets (Ternhag 2008; Rydquist 1910; Dunn 1965: 257–258) (see Figures 2 and 3). And around 1920 Bert Ohrlin (1896–1961), a Swedish immigrant, picked up the song “as harvest hand, a lumberjack, and a boxer… during his first years in the States,” including in North Dakota (Ohrlin 1973: 20).

Online search engines reveal the song’s increasing geographical and cultural dispersion by railroad workers, itinerant tradesmen, and soldiers in the 1910s, as well as its presence at formal social events that were initially male-only but gender inclusive by the decade’s end. In 1912, for example, Peter Johnson reported in the Rock Island Employees Magazine that he sang “I Am a Swede From North Dakota” for fellow Arkansas-based railroad workers with English, German, and Irish surnames (Johnson 1912). In faraway British Columbia, Ole Olson published a version – entitled “A Swede’s Trials” and commencing with “Hy ben Swede from North Dakota” – in the January 24, 1913 edition of The Lillooet Prospector (Olson 1913). A few months later Gordon K. Smith, financial secretary for Plasterer and Cement Masons’ Union Local 86 in Helena, Montana, described a Saturday night “smoker” for building laborers at which “Gus Lym rambled through a song entitled, ‘I’m a Swede from North Dakota,’ with great success” (Smith 1913). The song met similar approval when Plasterer and Cement Mason’s Local 179 of Youngstown, Ohio, gathered socially: “while the Steel City Four were getting their breath, Brother A.K. (Shorty) Irwin rendered ‘I Bane a Swede From North Dakota,’ and he fairly brought down the house with applause and responded again for an encore” (Gering 1915: 8). Hailing from Willard, Montana, but stationed in Siberia in March 1919, Private Ole Roget wrote a letter to his sister, published in the local Fallon County Times: “We had a minstrel show here last night, and it sure was very good. A Swede sang the song about being from North Dakota and took in the Minnesota State Fair” (Roget 1919). On March 25, 1919, the Republican Northwestern in Belvidere, Illinois, noted an anniversary celebration for Rebekah and Odd Fellow service organizations featuring Lawrence Griffeth performing “The Swede from North Dakota,” along with a banquet and dancing (Anonymous 1919).

Newspaper instances in ensuing decades situate the song in contexts extending beyond gatherings of often itinerant working-class males. In 1921, honoring a reader’s request, W.O. Hash of Youngstown, Alberta, sent a version to the “Poems Asked For” column of the Saskatoon Daily Star (Anonymous 1921). When the Ladies Aid of the Christian Church in Keithsburg, Illinois, met in 1922, Miss Gladys Hawkins followed Mrs. John Doak’s performance of “The Lamb at Church” with “That Swede from North Dakota” (Anonymous 1922). Halvor Halverson parodied the song to taunt a sports rival in Wisconsin’s Manitowoc Daily Herald (Halverson 1924): “A ban a Swede from North Dakota/A ban come to Man-it-ow-oc/A ban see the basketball game/Oh, by yiminy, ay feel so yolly/Because aye score ban/Manitowoc 22 and Two Rivers 19.” The November 9, 1933 edition of Wisconsin’s Eau Claire Leader-Telegram heralded a school carnival where “There is to be a ‘big Swede from North Dakota,’ a group of cowboys from the ‘old Chisholm trail,’ and a trumpet trio” (Anonymous 1933). In 1949 the Evening Tribune of Albert Lea, Minnesota, informed readers that, when the Sunnyside School Mother’s Club met, “a song by Alida and Ilo Flugum, ‘The Swede from North Dakota,’ got the program off to a good start” (Anonymous 1949). And in 1950 the song figured in both a column promoting the “Norwegian Hour” on Iowa’s KASI radio (Anonymous 1950a) and a Montana miners’ variety show (Anonymous 1950b).

Folklorists too found the song flourishing in Upper Midwestern working-class circles. In 1923 Robert Winslow Gordon, founder of the Archive of American Folksong at the Library of Congress in 1928, launched the column “Old Songs Men Have Sung” in the pulp magazine Adventure. Three readers sent him “The Swede”. These were D.F. Robbins, who heard it in Hibbing on the Minnesota Iron Range in 1924; George Hill of Field, British Columbia; and Fred P. Mansky, who called it “a Swede character song heard among the ranch and harvest fields of the west and middle western states. I got it from a Swede Hawaiian guitar player. I played with him for two years” (Gordon 1921–1930). In the 1930s, Earl C. Beck of Central Michigan University documented versions from a trio of Michigan lumberjacks: George McClain of Saint Louis, Tode Sherman of Kalkaska, and Nels Anderson of Baraga (Beck 1948: 182). During a 1938 field trip through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Alan Lomax recorded the song from Albert Francis “Bert” Graham amidst lumberjacks frequenting the barroom of Newberry’s Luce Hotel, and in Ontonagan from John E. “Happy Jack” Woodward, a singing guitarist and lumberjack active in the International Woodsmen of America union (Lomax 1938). Documentarians recording personal nicknames who were employed by the Works Progress Administration in Minnesota’s logging country discovered that “one lumberjack went by no other name than ‘North Dakota.’ His real name was Oleson, and when in his cups he was always singing a then-famous woods song, ‘The Swede From North Dakota’” (Writer’s Program 1941: 48). In 1939 Caleb Ananais Koljonen – born to Finnish immigrants in New York Mills, Minnesota but living in a California labor camp during construction of the Shasta Dam – sang for Sidney Robertson Cowell a version he called “The Disgusted Swede” (Cowell 1939). Neither Gordon nor Robertson Cowell published much of their massive folksong harvest, Lomax’s considerable writings mainly encompassed his native South, and Beck published only one version of “The Swede.”

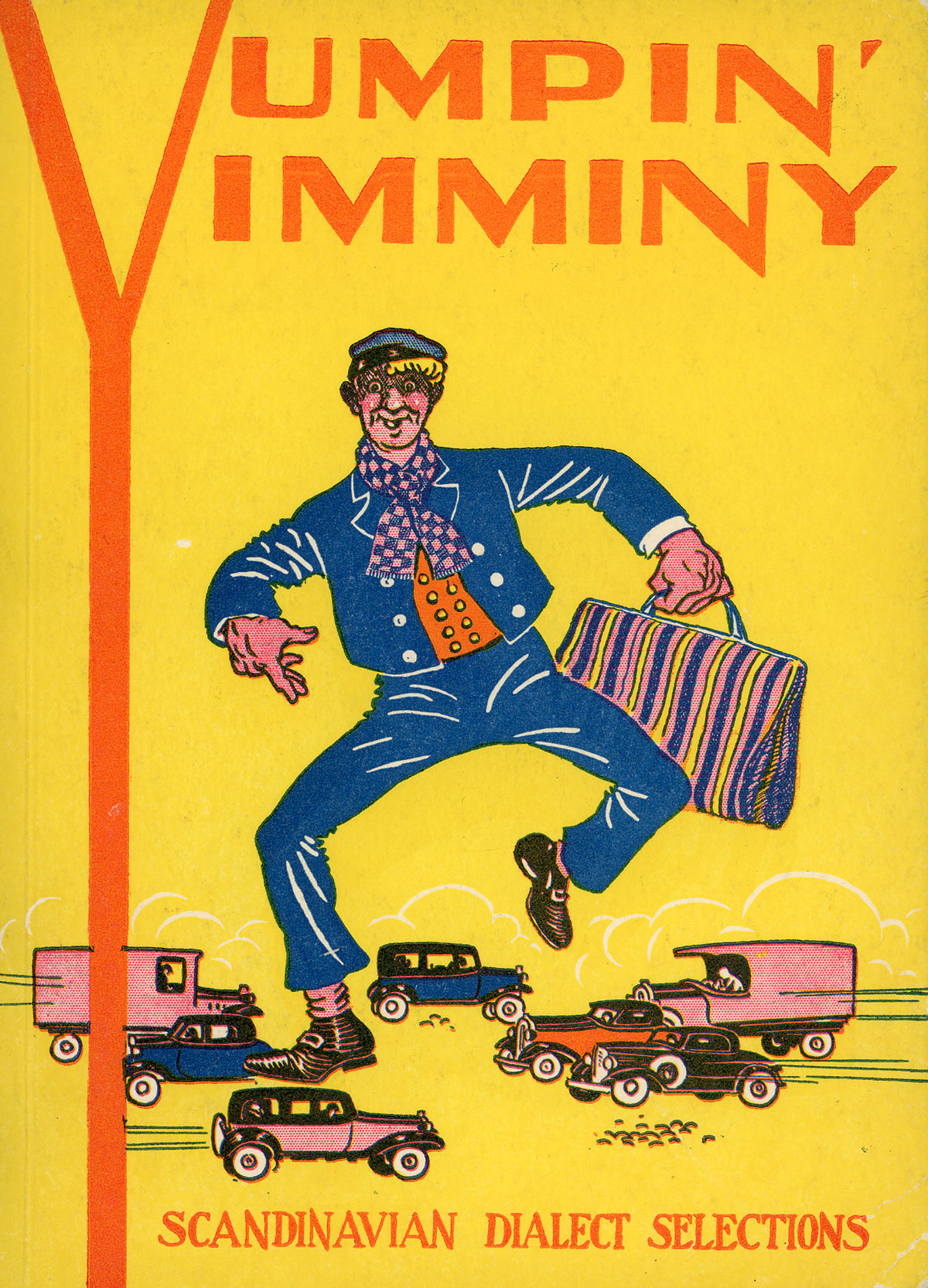

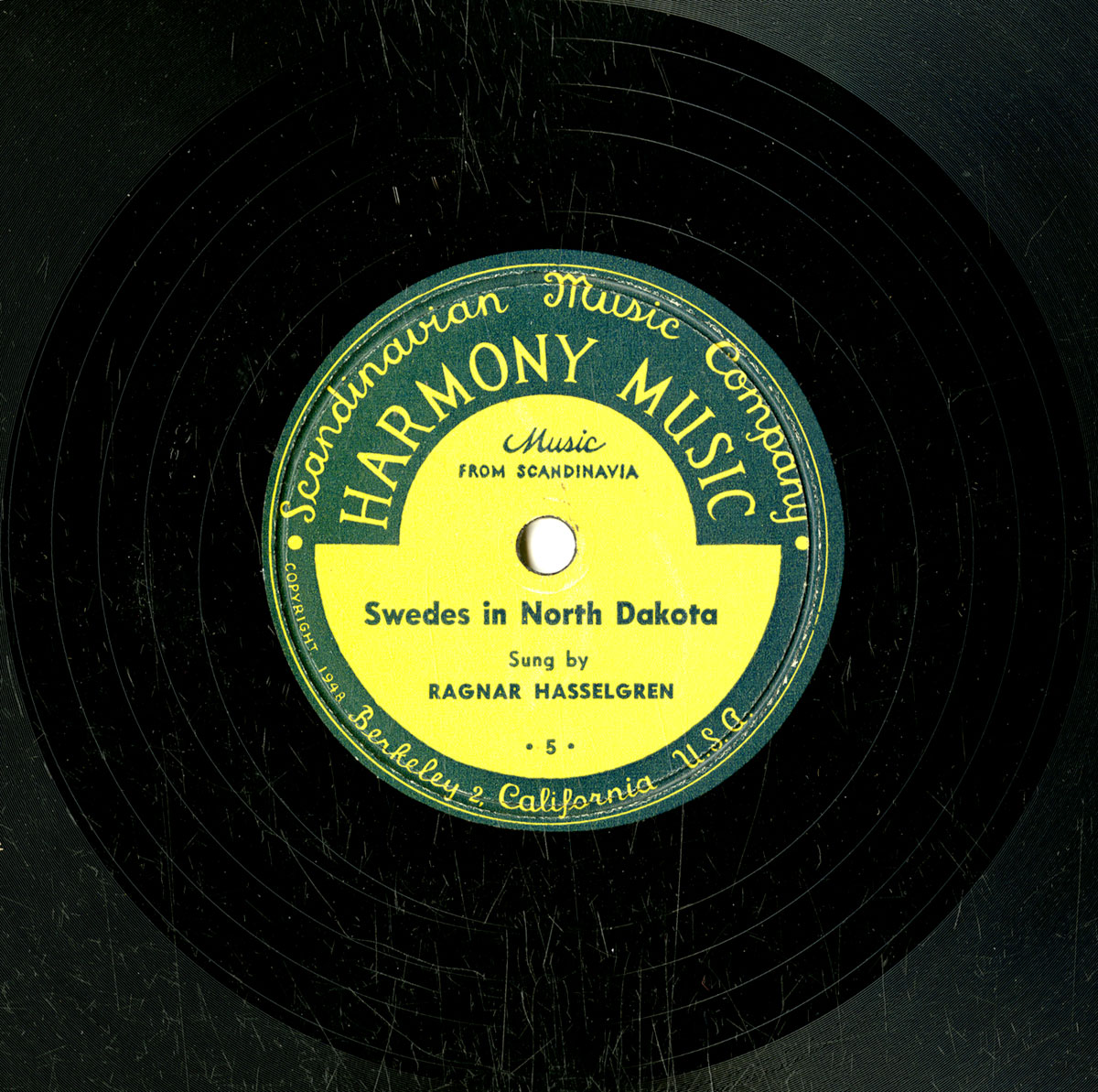

Buried in scholars’ archives, the song fared better with performers and aficionados. In 1918 Howard DeLong, a theater student at the University of North Dakota, included the song’s first two verses in a play “of the harvest fields of this state,” Barley Beards, performed in Grand Forks by Professor Frederick H. Koch’s Dakota Playmakers (Anonymous 1918). Born in a sod house on the Dakota prairie in 1898 to French Canadian immigrants, DeLong heard the song in summer 1913 from a Norwegian immigrant while they both worked on a threshing crew (Koch 1918: 19–20). That co-worker was likely the source for DeLong’s singing character, Olf Herdahl: “A Norwegian laborer of rather unkempt appearance. He speaks very broken English and has the habit of chewing snuff. He is about twenty-three years of age” (DeLong 1918: 4). Allan Edholm, a Minneapolis Swedish vaudevillian assuming the bondkomiker persona Ole i Gråthult (Ole from Cryingville), published “Swede from North Dakota” with “Ole the Swede” in a songbook otherwise featuring only Swedish and Norwegian texts (Edholm 1920: 2). George Milburn, an Oklahoma writer who had hopped freights while “on the bum,” published lyrics acquired from the aforementioned “Nels Anderson, author of The Hobo and a connoisseur of hobo poesy,” in The Hobo’s Hornbook (1930: 139; Turner 1970: 3). George T. Springer, a Minneapolis lawyer of German heritage who was raised amidst Swedes in Gladstone, Michigan, attributed the song to an “unknown author” in his 1932 folk humor anthology, Yumpin’ Yimminy: Scandinavian Dialect Selections (see Figures 4 and 5). The sons of Norwegian immigrants to North Dakota, Ernest and Clarence Iverson were popular entertainers known as Slim Jim and the Vagabond Kid on Minnesota radio stations. They featured “The Swede” in a self-published song collection (1939: 23). And in 1948, Ragnar Hasselgren, a Swedish-born singing guitarist raised on a Montana ranch, released the song as “Swedes in North Dakota” on a 78 rpm shellac record (Hasselgren 1948) (see Figure 6).

The cover of George T. Springer’s 1932 collection of Scandinavian American dialect humor depicts an immigrant bumpkin in the city. (Author’s collection).

Opening lyrics for George T. Springer’s version of the dialect song “Swede from North Dakota,” published in his 1932 humor anthology, Yumpin’ Yimminy. (Author’s collection).

The first commercial recording, with variant title, of the “Swede from North Dakota,” issued in 1948 on the Harmony Music label of Berkeley, California, and performed by Ragnar Hasselgren, son of Swedish immigrants to Montana. (Courtesy of Mills Music Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison).

“The Swede from North Dakota” crept into America’s ongoing folksong revivals thanks to Bert Ohrlin’s son, Glenn, best known for his deep cowboy song repertoire, who recorded his father’s version for an LP issued by the University of Illinois’ Campus Folksong Club in 1971. Three years later Anne-Charlotte Harvey – a Swedish singer, actress, and academician – recorded the Iverson songbook version as part of a series of “Snoose Boulevard” festivals (1972–1977) commemorating Minneapolis’s once thriving Swedish vaudeville scene (Harvey 1974; see also Sevig & Sevig 1993: #25). The Iverson/Harvey version figures in the repertoire of a contemporary Minneapolis female quintet, Flickorna Fem (The Five Girls). Ernest “Slim Jim” Iverson’s performance was issued posthumously, with the dialect title “Swede from Nort Dakota,” in 1980 from 1950s Minneapolis shows on KEYD radio (Iverson 1980). And in 1991 Joe Glazer, a longtime union activist dubbed “Labor’s Troubadour,” performed the Anderson/Milburn verses on a cassette honoring America’s immigrant workers past and present (Glazer 1991).

“The Swede” in Five Scenes

Extant versions of “The Swede from North Dakota” collectively offer a relatively standard plot sequentially unfolding, with variation, in five discrete scenes: a journey from North Dakota to Saint Paul; a trip from Saint Paul to a Minneapolis; misadventures with fellow Swedes in Minneapolis; encounters with a policeman, a judge, and jail; and an avowed return to North Dakota. Each scene condenses and combines working-class realities with widespread ethnic stereotypes and jocular stories circulating in oral tradition and vernacular publications. My transcription of Carl Bruce’s recording of lyrics learned in 1904 – the song’s earliest reported instance – offers a pathway into the many versions’ surface and nuanced meanings (Bruce 1981).

Scene 1 I been a Svede from Nort Dakota, vork on a farmstead about vun year. I go down to Minnesota yust to look on da big State Fair. So I buy me a ticket and I buy me a bottle, dressing up yust out of sight. Yumpin’ Yiminy! I feel yolly, feel yust like I vant to fight. I yump on Yim Hill’s little red vagon, take along my alcohol. Still vaking up da very next morning in da city called Saint Paul.

Alternatively commencing with “Great big Swede,” as in Ludwig Rydquist’s version, these opening lines resonated deeply with Upper Midwesterners in the early 1900s. One-fifth of the 1.2 million Swedes immigrating to the United States 1865–1930 settled in Minnesota (Beijbom 1980: 971–973). In 1910, Norwegians were five times more numerous than Swedes in North Dakota, where not a single settlement was primarily Swedish (Thorson 1988: 186, 214; Sherman 1983: 20–21, 38, 55, 72, 92–93, 115). Yet “the Dakotas became thickly dotted with Swedes” in the 1880s, as migratory summer workers – many of them wintertime lumberjacks in Minnesota camps – harvested wheat on the Red River Valley’s massive “bonanza farms” (Shannon 1945: 49, 159). On July 25, 1908, the Minneapolis Journal reported “upwards of 5,000 men” gathered in Minneapolis as part of a “harvest army… on their annual pilgrimage” westward to North Dakota (Rosheim 1978: 58). By late August many seasonal workers headed eastward as the late summer Minnesota State Fair – established in Saint Paul in 1854, the largest in the USA – always followed the harvest.

The Northern Pacific Railroad, which maintained immigration offices in New York and Saint Paul, was actively engaged in “advertising for and transporting workers to [and from] the grain fields” (Shannon 1945: 43; Drache 1964: 113). Run by the Canadian-born railroad executive James J. Hill (1838–1916), the Northern Pacific extended its tracks across America’s northern plains from Minneapolis to Seattle in the years 1883–1893. Known for his gruff, earthy, hands-on style, Hill figured from the late 1880s on as “Yim Hill” in circulating anecdotes like this oft-printed example from the September 1893 edition of Milling, a Chicago trade journal:

A Swede workman on the Great Northern railway last winter was discharged by Jim Hill for not attending properly to his work. He met a friend, to whom he tells with great gusto the story of his dismissal.

“Aye bin vorkin’ on das railroad, an’ aye bin tired vorkin’, an’ lean on mae shovel, an’ Yim Hill he cum long, hae tell me: ‘You big Norvegan son of gun, what for you no vorkin’, you tank aye no want mae road finished this year; you go by boss an’ gate you pay.’ An’ aye go by boss an’ gate mae pay, an’ aye laugh meself sick, an’ das geud yoke on Yim Hill: hae call me Norvegan son of gun, an’ haer aye bin Swede fallar all mae life” (Anonymous 1893: 276).

About the same time “Jim Hill wagon” or “Yim Hill vagon” became synonymous with the Great Northern Railway (e.g. Anonymous 1897).

The Swede/North Dakota association and comic Scandihoovian English (especially swapping “y” for “j,” “v” for “w,” and “d” for “th”) were simultaneously prominent in the Upper Midwest thanks to Cleveland-born actor/playwright Gus Heege (1862–1898). A gifted mimic of German descent, Heege spent time between tours in the 1880s in northwestern Wisconsin’s Saint Croix Valley, where “Swedes, Norwegians, and Danes settled in great numbers” to farm and log (Anonymous 1895). He subsequently created and starred in a trio of plays – Ole Olson (1888), Yon Yonson (1890), and A Yenuine Yentleman (1895) – that were sustained after his death by Ben Hendricks (1868–1930) until 1912, spawning a succession of “Swedish-dialect companies” trouping “through Scandinavian strongholds in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Nebraska, and the Pacific Northwest” (Magnuson 2008: 67; see also Harvey 2001; and Harvey 2015: 253–258). Notably, Yon Yonson featured “a good-hearted, simple-minded unsophisticated Swede” traveling from North Dakota to a Minnesota lumber camp (Anonymous 1904a). When Henry’s Big Specialty Company subsequently toured Minnesota in 1908, one of its acts was “Harry Roberts – That Swede from North Dakota” (Anonymous 1908).

The “stage Swedes” Heege, Hendricks, Roberts, and other traveling Scandihoovian comedians contributed to a vernacular stereotype articulated by theatre historian Anne-Charlotte Harvey: “Yonnie (Ole, Sven) is big and strong… He works with his hands, overwhelmingly as a farmhand or lumberjack… His occupation, and many of his songs, place him firmly in the Upper Midwest” (Harvey 1996: 61). Beyond the stage, other folk and vernacular expressions added binge drinking and pugnacity to the stereotype. Jim Hill, for example, famously proclaimed: “Give me Swedes, snuff, and whiskey, and I’ll build a railroad through hell” (Dregni 2011: 99; Roediger & Esch 2012: 83). Ola Värmlänning, a powerful, good-natured Swedish laborer with an “addiction to the bottle” and inclinations to clobber Irish policemen was the subject of anecdotes and a chapbook circulating in Minneapolis/Saint Paul from the 1890s–1910s (Swanson 1948). During that period scores of Swedish wrestlers, boxers, and barroom carousers were dubbed “The Terrible Swede” or “The Giant Swede” in newspaper accounts, including “Nelson, the Terrible Swede from North Dakota” (Anonymous 1901) and Martin Foss, billed by the Minneapolis Tribune as the “Giant Swede from North Dakota” (Anonymous 1904b).

No wonder the song’s North Dakota Swede is a seasonal single hired hand rather than a settled married homesteader. Squandering hard-earned pay on a bottle and “out of sight” attire, he exemplifies the era’s stock male Scandihoovian: simple, showy, dialect-spewing, bibulous, pugilistic yet “yolly”. His humble ticket on “Yim Hill’s” Great Northern Railway is among fellow workers in the caboose (“little red vagon”) that carries him to Saint Paul.

Scene 2 Valking ‘round da street in Saint Paul, ain’t seen a fella anywhere, So I yump on streetcar to Minneapolis; bet your life lots Svede men dere. Valking round in Sout’ Minneapolis, go into Billy’s place for fun. Vell, I meet some yolly Svede pals to slap me on da back, say “God dag, Sven!”

Our “Svede,” once arrived, is more interested in his immigrant compatriots than the State Fair. Swedes in Saint Paul were outnumbered by Germans, Irish, Slavs, and Norwegians, but Minneapolis had two “Swede Towns,” each with a “Snoose Boulevard” named for Scandinavian males’ affection for snuff or snus. Washington Avenue, on the downtown’s margin, was a place “where lumberjacks, farmhands, and other seasonal workers… hung out.” Cedar Avenue in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of South Minneapolis “was lined with Scandinavian businesses, saloons, and theaters” (Lanegran 2001: 51–52). That was where Nels Anderson and another hobo headed around 1908. Hoping to hop trains to Montana where there was work on the railroad “extra gangs” of James Hill’s Great Northern line, the companions “arrived hungry in Minneapolis, and found our way as if by instinct to that area of a city for wandering men, ‘the main stem.’ In that city it was called… ‘Seven Corners,’ where three or four streets met… a labor market for workers in the lumber woods, workers in the iron mines, farm workers, construction workers” (Anderson 1975: 68–69).

“Billy’s place” as a Swedish hangout is exclusive to Carl Bruce’s singing. Other versions mention “a cabaret,” “a saloon,” the “Pioneer Saloon,” and most frequently “Stockholm” – perhaps invoking “Stockholm Olson,” who ran combination dance halls and saloons with “bad reputations” near Seven Corners (Rosheim 1978: 49). It may possibly refer instead to the Stockholm Bar and Café, a seedy Washington Avenue establishment favored by Swedes that featured music and dancing.

Upon entering the bar, our hero’s “yolly Svede pals” greet him in his native tongue, although the pat on the back and the homophonic resonance of “God dag” (Good day) with “good dog” suggests comic double meaning. The name Sven revealed in this scene could either be the Swede’s name or a generic designation. Sven, along with Ole and Yon, were not only Gus Heege’s stage personas, but also the names of stock characters figuring in a spate of Scandihoovian jokes that began flourishing in the 1890s. Paralleling Irish America’s Pat and Mike, these names signified cheerful, strong, and dim immigrant males (Leary 2001: 57, 63).

Scene 3 I look around and I feel so funny, ain’t seen dem fellas before, I tink. But I feel foxy an’ say, “Hey fellas, come and have a, have a drink.” So ve take drink and I feel so yolly, ve begin to dance and sing. And I say to all Svede fellas: “I skall pay for da whole darn ting.”

Comfortably situated with newly-met “Svede fellas,” our profligate hero, slipping into Swedish (skall/shall), whoops it up. In other versions, like Rydquist’s, a “great big Svede girl” replaces the “fellas”:

I turned around and feeled so funny, never seen this girl, I think, I ban foxy, say, “Hello Tillie, wouldn’t you like to have a drink?”

Since the 1890s there has been a “good” female Scandihoovian character “most often called Hilda or Hulda, sometimes Tilly (Tillie)… or Lena,” typically a domestic servant or a dairy maid, but this stock figure has an occasional “bad” counterpart, “indistinguishable from such other American female archetypes as the vamp and the gangster moll” (Harvey 1996: 62). In Fred Mansky’s version Tillie, who calls our hero Ole not Sven, is both seductress and thief (Gordon 1921–1930):

Ve take vun drink den Aye take anudder, bye and bye Aye feel purty gude. Ven Aye come to Aye got no money. She take my whole damn pocket-buke.

The wandering Swede fared better with Bert Ohrlin, a singer and sometime song-composer who may have made up the unique last lines of his condensed rendition (Ohrlin 1973: 20):

I landed down in Minneapolis, dere I vent on one big spree. Now all the Swedes in Minnesota look a little bit like me.

At least three early instances of our Swede’s song, however, conclude his adventures on the streets of Minneapolis without having entered a tavern. They align with Nels Anderson’s 1907 remembrance of the dynamite man Dino’s singing (Anderson 1975: 54):

I go down to Seven Corners where Salvation Army play; One dem womans she come to me, dis is what dat woman say; She say, “Will you work for Yesus?” I say, “How much Yesus pay?” She say, “Yesus don’t pay notting.” I say, “I won’t work today.”

Some Old and New World Swedes were active in the Salvation Army, whose office in Swedish Minneapolis sponsored a parading band with “bonnets, bugles, and all” (Rosheim 1978: 64–65, 81). Committed to a politically conservative brand of Christianity and temperance, derided by opponents as the “Starvation Army” for ignoring economic and class conflict to preach “pie in the sky when you die,” this organization often carried out its mission musically on urban skid row street corners, where its fervent soldiers vied in the early twentieth century with soapbox orators of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Associated with the Swedish immigrant troubadour Joe Hill and devoted to organizing the migratory working class as well as encouraging direct action via strikes to win better conditions, the IWW was in turn disparaged by casting its initials into the phrases “I Won’t Work.” The Hope Pioneer, for example, reported that in Minot, “one of the ‘toughest towns’ in North Dakota,” 150 men were arrested during the “‘I Won’t Work’ riots” of August 1913 (Anonymous 1914a).

The Salvation Army in “The Swede” episode derives from an anecdote circulating widely with slight variation in newspapers from 1886–1887:

The Salvation Army is now in full blast and has a large number of followers.

The other day one of the soldiers approached a Swede who was standing on the sidewalk and asked “Don’t you want to work for Jesus?” “Naw,” replied the Swede, “I got a yob.” (Anonymous 1886)

Other instances emphasize far better pay for a “yob” in the woods, on a farm, or on a railroad gang for “Yon Yonson,” “Ole Olsen,” or “Yim Hill.”

Scene 4 Then the next morning I been a-waked up by the fella they call “The Bull.” Him says to me, “Ten days, ten dollars, ‘cause you been so awful full.” I look in my pocket, I ain’t got no money. Judge says, “Här you got no bail?” All dat is left for dis poor Svede man is for him to lay ten days in yail.

In the early twentieth century unmarried seasonal migratory workers, Swedish or otherwise, caroused in taverns between jobs, especially during “boom and bust times,” and many served short sentences in the Minneapolis City Workhouse for drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and vagrancy (Lintelman 2001: 61). An eventual Scandihoovian dialect singer raised on a large Upper Midwestern farm employing hired men, Bruce Bollerud (1934–2020) described the pattern: “They were usually single guys. And a lot of times they wouldn’t have any relatives close by. They’d work real hard and then when they got paid, they might go on a big drunk. And they might be out of commission for three, four days, or a week” (Bollerud 1987).

A privately-employed policemen, sometimes known in hobo’s argot as the “railroad bull” or the “yard bull,” hauls in our hungover hero, who has presumably slept rough in some hobo jungle along the tracks. The Swede’s arrest, penniless homeless state, courtroom appearance, and ten days or ten dollars sentencing resemble the fate of another Scandihoovian folksong hero:

Ole Olson, you hobo from Norway, you got drunk and you went on a spree. I fine you ten days and ten dollars, and I hope you remember the day.

“Ole the Hobo from Norway” surfaced around 1890 in the repertoires of immigrant, working-class Upper Midwesterners (Leary & March 1993: 258–262). The remarkably intertwined existence of these songs merits more exploration than can be offered here, but they reflect experiences and attitudes of many migratory workers summarized in Nels Anderson’s study The Hobo: “In many ways, the migratory worker is ‘a man without a country.’ By the very nature of his occupation he is deprived of the ballot, and liable when not at work to arrest for vagrancy and trespassing… Most of the songs he sings are songs of protest” (Anderson 1923: 166–167).

Anderson’s singing fellow worker, Dino, had been arrested “a time or two when on a drunk… and put in chain gangs doing street repair work” (Anderson 1975: 58). The less severe 10 days or 10 dollars option was common in Minnesota in the 1880s–1910s. In March 1882, for example, a Saint Paul newspaper reported that “C. Moore got drunk and raised Cain, and for his trouble received a sentence of ten days or ten dollars yesterday morning. He paid his bill and went on his way rejoicing” (Anonymous 1882). Twenty-five years later, “Fred Lester, a man who claimed to have been working on the Minnesota & International railroad, was given ten days or ten dollars and Officer McGivern was sent with him to railroad headquarters to get the money to pay the fine” (Anonymous 1907). A related joke circulated from the Upper Midwest through the Pacific Northwest, typically involving the Irish stock character Pat as a migratory immigrant worker: “The judge has just announced his decision ‘Take your choice, ten days or ten dollars,’ when Pat holds out his hand… ‘Plase your wurship give me the tin dollars’” (Anonymous 1891).

Our Swede’s Scene 4 likewise featured double-meanings. While only Swedish-speakers might realize that “full” means drunk in Swedish, the homophony of “yail” (jail) and “Yale,” the elite New England university, has long sparked humor. William F. Kirk (1877–1927) – a Minnesota-born, Wisconsin-raised, Anglo-American – authored The Norsk Nightingale (1905), an anthology of Scandihoovian “lumberyack” verses wildly popular in the Upper Midwest. He also wrote a series of humorous Minneapolis newspaper columns featuring Steena the Swedish maid, including an installment adapting a persistent joke in Upper Midwestern oral tradition. A weeping Steena laments that her brother “ban in yail.” Confounded, the mistress of the house replies: “If I had a brother in Yale, I wouldn’t cry… I would think it a great honor” (Kirk 1910). Nowadays when Flickorna Fem’s Elisabeth Skoglund performs “The Swede from North Dakota,” the audience’s “biggest laugh” responds to the yail/Yale incongruity (Clark 2016).

Scene 5 So I go back to Nort’ Dakota, get a yob on a farm somewhere, And I said to all Svede fellas, “Dey can go to heck wit the da big State Fair.”

Conforming to a pattern common among male seasonal workers, particularly from the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries, our hero returns to previous work after a short spree. His direct “to heck wit’” admonition to “all Svede fellas,” coupled with an earlier decision to prioritize carousing with often shady immigrant countrymen, suggests mixed feelings about the “big State Fair” from the outset. It also conveys wariness of the “big State,” especially evident in the big city where naïve immigrant bumpkins can fall victim not only to their own kind’s desperate chicanery, but also to the host culture’s unwelcoming hierarchical brutality. Thwarted and chagrined, yet paradoxically refreshed by debauchery, The Swede returns to the dull yet safe predictable hinterlands from whence he came, a hapless seasonal worker whose fictitious journey ultimately goes nowhere. Consideration of the entire song’s cultural contexts and meanings, however, certainly gets us somewhere.

The Significance of “The Swede”

In 1913, as “The Swede from North Dakota” circulated vigorously, John Lomax delivered a provocative presidential address at the American Folklore Society’s annual meeting. Countering declarations by “the best critics of the ballad” that no such narrative folksongs had emerged in America, Lomax asserted they “do exist and are being made today” by miners, cowboys, “the negro,” Great Lakes sailors, soldiers, railroaders, and “the down-and-out classes – the outcast girl, the dope fiend, the jail-bird, and the tramp” (Lomax 1915: 1, 3). Perhaps because of longstanding academic and popular notions that American folk ballads are exclusively of Anglo-Celtic or African American origins and subject matter, or perhaps because he worked mainly in the South, Lomax did not include ballads focused on Euro-American immigrants.

Despite Lomax’s omission, “The Swede from North Dakota,” is a fully American folk ballad, a prime exemplar of the “singing ambivalence” historian Victor Greene found threading through the “foreign” language songs of America’s immigrant and ethnic communities (Greene 2004). A broken-English dialect song sprinkled with Swedish words, it owes its origin either to someone resembling our earliest sources for the song – Swedish immigrants, Carl Bruce and Bert Ohrlin; Swedish immigrants’ children, Ludwig Rydquist and Nels Anderson – or to some close associate like the roving Irishman, Frank C. Hogan (1875–1959). A profile of Hogan in a Minneapolis-based trade journal, The Mississippi Valley Lumberman, claimed that he not only “knew every living soul in every town that he made,” but also “made himself famous by composing a song about the ‘Swede from North Dakota’ who visited the Minnesota Fair” (Anonymous 1914b: 55) (see Figure 7). Although attributions or claims of authorship attached to someone known for performing a particular song are not uncommon, further evidence on Hogan’s behalf from The Mississippi Valley Lumberman reveals that, as a timber grader turned traveling salesman for several northwest Minnesota lumber mills beginning in the mid-1890s, he mingled often with Swedes and other itinerant workers during both regular stints in North Dakota along Jim Hill’s Great Northern Railroad, and frequent returns to Minneapolis that included visiting his mother and “taking in the big state fair” (Anonymous 1902). Convivial, with a wide circle of acquaintances, Hogan was also known for performing at the rowdy social events of such facetiously named lumbermen’s organizations as The Cuspidor Club and The Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo, entertaining one such gathering “with a Swedish monologue” (Anonymous 1912).

Whether or not a Hogan composition, the song quickly circulated in differing versions to become, in Barbro Klein’s terms, an ethnic/local cultural form co-existing with regional cultural blends. Indeed, when John Lomax launched his 1913 manifesto, the song was already the property of the Upper Midwest’s working class; of Irish, Yankees, Germans, Finns, Norwegians, Swedes, and more; of the members and observers of ethnically diverse regionally blended migratory railroad gangs, harvest hands, and lumberjacks who tramped seasonally from job-to-job, sometimes enduring fines and jail.

At the same time, the song’s characters, settings, and themes intertwined with larger pre-existing and ongoing stereotypes, stories, songs circulating through oral tradition, newspapers, ephemeral publications, and the stage, to render “The Swede from North Dakota” accessible as a familiar humorous iconic figure to an audience beyond migratory male workers and fellow travelers. And by the 1920s, as the original context for the song receded into the past, what once was dangerous and vulgar was transformed through nostalgia into a safe and amusing remembrance of the wild old days, appropriate for gatherings of the Ladies Aid and elementary school carnivals.

The song’s continuing currency, launched by folksong revivalists in the 1970s, has a similar distribution. There is a core constituency of Minneapolis Scandinavians who perform and savor the Swede’s antics as part of their ethnic/local cultural heritage. As settled citizens, however humble their ancestral immigrant origins, they can both sympathize with and find cosmopolitan pleasure in the foibles of a rootless, feckless Swedish bumpkin from rustic North Dakota. Upper Midwesterners from other backgrounds also savor comic representations of the region’s culturally blended working-class past; and both labor historians and ballad scholars appreciate the song’s gritty topic and twisting trajectory. Moreover, as Nina Clark of Flickorna Fem observed, since Minneapolis has a large ethnic Swedish population and the bordering counties of rural North Dakota are correspondingly Norwegian, there is a diplomatic advantage to urban Minnesota Swedes in poking fun at rural North Dakota’s scant and scattered fellow Swedes rather than deriding the far more populous Norwegian North Dakotans (Clark 2016).

Beyond exuding a goofy charm, the varied, very real existence of the fictitious circulating “Swede from North Dakota” has much to tell us about the complicated ways in which expressive forms generated by the presence of new immigrant workers can assume unforeseen, shifting, and enduring significance.

Acknowledgements

With gratitude I salute Paul F. Anderson, incomparable researcher on early Swedish American entertainers, who kindly read and commented on several drafts of this essay; folklorist Marcus Cederström, who generously assisted with access to and English summaries of Uno Ericson’s 1982 Carl Bruce program on Sveriges Radio; the Swedish national library, Kungliga Biblioteket, which loaned a copy of the Ericson/Bruce program; and two anonymous reviewers whose astute comments contributed to this essay’s final version.

References

Literature

Anderson, Nels 1923: The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Anderson, Nels 1975: The American Hobo: An Autobiography. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Anonymous 1893: “Geud Yoke on Yim Hill.” Milling 3(4): 276.

Anonymous 2013: The Swedish Can Really “Break a Leg.” In: Midway Village Museum Collections Blog, July 15. Rockford, Illinois.

Beck, Earl Clifton 1948: Lore of the Lumber Camps. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Beijbom, Ulf 1980: Swedes. In: Stephan Thernstrom (ed.), Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 971–981.

Cowell, Sidney Robertson 1939: California Gold: Northern California Folk Music from the Thirties. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

Dorson, Richard M. 1947: Folk Traditions of the Upper Peninsula. Michigan History 31(1): 48–65.

Drache, Hiram M. 1964: The Day of the Bonanza: A History of Bonanza Farming in the Red River Valley of the North. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies.

Dregni, Eric 2011: Vikings in the Attic: In Search of Nordic America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dunn, James Taylor 1965: The Saint Croix: Midwest Border River. New York City: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Edholm, Allan 1920: Olle i Gråthults Sångbok: Svenska och Norska Sånger och Visor med musik [Olle from Cryingville’s songbook: Swedish and Norwegian songs and poems with music]. Minneapolis: Scandia Publishing and Importing.

Ericson, Uno 1971: På nöjets estrader: Bondkomiker skildrade av Uno Myggan Ericson [On the entertainment stage: Rustic comedians depicted by Uno “The Mosquito” Ericson]. Stockholm: Bonnier.

Gering, Joseph 1915: From Youngstown, Ohio. The Plasterer 9: 8.

Greene, Victor 2004: A Singing Ambivalence: American Immigrants between Old World and New, 1830–1930. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press.

Hall, Joan Houston 2002: Dictionary of American Regional English, Volume IV. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, Anne-Charlotte 1996: Holy Yumpin’ Yiminy: Scandinavian Immigrant Stereotypes in the Early Twentieth Century American Musical. In: Robert Lawson-Peebles (ed.), Approaches to the American Musical. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 55–71.

Harvey, Anne-Charlotte 2001: Performing Ethnicity: The Role of Swedish Theatre in the Twin Cities. In: Philip J. Anderson & Dag Blanck (eds.), Swedes in the Twin Cities: Immigrant Life and Minnesota’s Urban Frontier. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 149–172.

Harvey, Anne-Charlotte 2015: Yon Yonson: The Original Dumb Swede – but perhaps not so dumb. The Swedish-American Historical Quarterly 66(4): 248–274.

Iverson, Clarence & Ernest Iverson 1939: Slim Jim and the Vagabond Kid Song Collection. Minneapolis: self-published.

Johnson, Peter 1912: “Argenta, Ark. News.” Rock Island Employee Magazine 6: 38.

Kirk, William F. 1905: The Norsk Nightingale. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company.

Klein, Barbro 2004: Old Maps and New Worlds. In: Philip J. Anderson, Dag Blanck & Byron J. Nordstrom (eds.), Scandinavians in Old and New Lands: Essays in Honor of H. Arnold Barton. Chicago: Swedish-American Historical Association, 237–263.

Koch, Frederick H. 1918: The Dakota Playmakers: An Historical Sketch. The Quarterly Journal of the University of North Dakota 9(1): 14–21.

Lanegran, David A. 2001: Swedish Neighborhoods of the Twin Cities. In: Philip J. Anderson & Dag Blanck (eds.), Swedes in the Twin Cities: Immigrant Life and Minnesota’s Urban Frontier. Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 39–56.

Laws, G. Malcolm 1964: Native American Balladry. Philadelphia: American Folklore Society.

Leary, James P. 2001: So Ole Says to Lena: Folk Humor of the Upper Midwest. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leary, James P. 2015: Folksongs of another America: Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest, 1937–1946. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leary, James P. & Richard March 1993: Farm, Forest and Factory: Songs of Midwestern Labor. In: Archie Green (ed.), Songs about Work: Essays in Occupational Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Folklore Institute Special Publications, No. 3: 253–286.

Lintelman, Joy 2001: “Unfortunates” and “City Guests”: Swedish American Inmates and the Minneapolis City Workhouse, 1907. In: Philip J. Anderson & Dag Blanck (eds.), Swedes in the Twin Cities: Immigrant Life and Minnesota’s Urban Frontier. Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 57–76.

Lomax, John 1915: Some Types of American Folksong. Journal of American Folklore 28(107): 1–17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/534554

Magnuson, Landis K. 2008: Ole Olson and Companions as Others: Swedish-Dialect Characters and the Question of Scandinavian Acculturation. Theatre History Studies 28: 64–111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ths.2008.0026

Milburn, George 1930: The Hobo’s Hornbook: A Repertory for a Gutter Jongleur. New York City: Ives Washburn.

Ohrlin, Glenn 1973: The Hell-bound Train: A Cowboy Songbook. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Roediger, David R. & Elizabeth D. Esch 2012: The Production of Difference: Race and the Management of Labor in U.S. History. New York City: Oxford University Press.

Rosheim, David L. 1978: The Other Minneapolis: A History of the Minneapolis Skid Row. Maquoketa, Iowa: The Andromeda Press.

Sevig, Mike & Else Sevig, with Anne-Charlotte Harvey 1993: Mike & Else’s Swedish Songbook. Bloomington, Minnesota: Skandisk.

Shannon, Fred A. 1945: The Farmer’s Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860–1897. New York City: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Sherman, William C. 1983: Prairie Mosaic: An Ethnic Atlas of Rural North Dakota. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies.

Smith, Gordon K. 1913: From Helena, Mont. The Plasterer 17: 6.

Springer, George T. 1932: Yumpin’ Yimminy: Scandinavian Dialect Selections. Long Prairie, Minnesota: The Hart Publications.

Swanson, Roy 1948: A Swedish Immigrant Folk Figure: Ola Värmlänning. Minnesota History 29: 105–113.

Ternhag, Gunnar (ed.) 2008: Samlade visor: Perspektiv på handskrivna visböcker (Collected songs: Perspective on handwritten songbooks). Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur.

Thorson, Playford V. 1988: Scandinavians. In: William C. Sherman & Playford V. Thorson (eds.), Plains Folk: North Dakota’s Ethnic History. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 186–216.

Turner, Steven 1970: George Milburn. Austin, Texas: Steck-Vaughn Company.

Wright, Robert L. 1965: Swedish Emigrant Ballads. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Minnesota 1941: Logging Town: The Story of Grand Rapids, Minnesota. Grand Rapids: Village of Grand Rapids.

Newspapers

Anonymous 1882: City Globules. Saint Paul Daily Globe. Saint Paul, Minnesota, March 23.

Anonymous 1886: Kansas State News. Cherryvale Bulletin. Cherryvale, Kansas, December 9.

Anonymous 1891: A Versatile Judge. The Dalles Daily Chronicle. The Dalles, Oregon, November 13.

Anonymous 1895: Preparing a Swedish Delicacy: “Yon Yonson” Heege Describes the Process in “Little Scandinavia.” New York Times. New York City, January 28.

Anonymous 1897: Local Brevities. Willmar Tribune. Willmar, Minnesota, April 6.

Anonymous 1901: Eagles at Clam Bake. Duluth Evening Herald. Duluth, Minnesota, June 24.

Anonymous 1902: Personal Mention. Mississippi Valley Lumberman. Minneapolis, Minnesota, September 5.

Anonymous 1904a: Yon Yonson at the Grand. Saint Paul Globe. Saint Paul, Minnesota, March 6.

Anonymous 1904b: Moth was a Winner. Minneapolis Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 10.

Anonymous 1907: Ten Days or Ten Dollars. Brainerd Dispatch. Brainerd, Minnesota, June 26.

Anonymous 1908: Henry’s Big Specialty Company Advertisement. Princeton Union. Princeton, Minnesota, September 24.

Anonymous 1912: Big Class of Kittens Will Learn Mysteries of Hoo Hoo Order. Spokane Chronicle. Spokane, Washington, February 3.

Anonymous 1914a: [Untitled]. The Hope Pioneer. Hope, North Dakota, January 15.

Anonymous 1914b: Something about Some of Your Friends. The Mississippi Valley Lumberman 45: 41.

Anonymous 1918: Playmakers Have Dress Rehearsal. Grand Forks Herald. Grand Forks, North Dakota, April 11.

Anonymous 1919: Owls Celebrate their Birthday. Republican Northwestern. Belvidere, Illinois, March 25.

Anonymous 1921: Poems Asked For. Saskatoon Star. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, March 7.

Anonymous 1922: Keithsburg Aid Society Stages Pleasant Party. Monmouth Daily Atlas. Monmouth, Illinois, December 29.

Anonymous 1933: Junior High Carnival Set for Today. Eau Claire Leader. Eau Claire, Wisconsin, November 9.

Anonymous 1949: Antiques Displayed at Meeting. Evening Tribune. Albert Lea, Minnesota, May 14.

Anonymous 1950a: Static from KASI. Ames Daily Tribune. Ames, Iowa, January 18.

Anonymous 1950b: Giant Variety Program is Arranged. Anaconda Copper Miner’s News. Anaconda, Montana, May 7.

Halverson, Halvor 1924: A Laugh or Two. Manitowoc Daily Herald. Manitowoc, Wisconsin, January 24.

Kirk, William F. 1910: Steena’s Brother in Jail. Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2.

Olson, Ole 1913: A Swede’s Trials. Lillooet Prospector. Lillooet, British Columbia, Canada, January 4.

Roget, Ole 1919: Letter from Ole Roget. Fallon County Times. Baker, Montana, March 13.

Archives

DeLong, Howard 1918: Barley Beards. Unpublished manuscript, Frederick H. Koch Papers, University of Miami Special Collections. Miami, Florida.

Gordon, Robert Winslow 1921–1930: Gordon Manuscripts. Unpublished. Washington, D.C.: American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

Rydquist, Ludwig 1910: Notebook. Unpublished manuscript, in James Taylor Dunn Papers. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society.

Interviews

Bollerud, Bruce 1987: Interview by James P. Leary and Richard March, Madison, Wisconsin, November 14.

Bruce, Carl 1980: Interview by Märta Ramsten & Uno M. Ericson, Rockford, Illinois, February 4. Quoted in 1981: From Sweden to America: Swedish Emigrant Songs. Stockholm: Caprice Records 2011 LP and booklet.

Clark, Nina 2016: Conversation with James P. Leary, Minneapolis, Minnesota, April.

Sound Recordings

Bruce, Carl 1981: “I been a Swede from North Dakota,” field recording by Märta Ramsten & Uno M. Ericson. From Sweden to America: Swedish Emigrant Songs. Stockholm: Caprice Records 2011 LP.

Ericson, Uno “Myggan” & Carl Bruce 1982: Ett program om Carl Bruce Rockford Illinois av Uno “Myggan” Ericson [A program about Carl Bruce, Rockford, Illinois, by Uno “The Mosquito” Ericson], August 29. Stockholm: Sveriges Radio.

Glazer, Joe 1991: Welcome to America: Joe Glazer Sings Songs of the American Immigrants. Silver Springs, Maryland: Collector Records cassette.

Harvey, Anne-Charlotte 1974: Return to Snoose Boulevard: More Songs from the Scandinavian Emigrant Heritage. Minneapolis: Olle i Skratthult Project LP OLLE SP-224.

Hasselgren, Ragnar 1948: Swedes in North Dakota. Berkeley, California: Harmony Music 78 RPM record, series number 5.

Iverson, Ernest 1980: The Swede from Nort Dakota. Saint Paul: Hep Records LP HEP-00228.

Lomax, Alan 1938: Alan Lomax Collection of Michigan and Wisconsin Recordings. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

Ohrlin, Glenn 1971: Glenn Ohrlin – the Hell-bound Train. Urbana, Illinois: Campus Folksong Club Records – CFC 301.

James P. Leary is an emeritus professor of folklore and Scandinavian studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he co-founded the Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures. His research on the folklore of the Upper Midwest’s diverse peoples has resulted in numerous museum exhibits, radio productions, documentary sound recordings, films, essays, and books that include So Ole Says to Lena: Folk Humor of the Upper Midwest and Folksongs of Another America: Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest, 1937–1946.