Introduction

Linguistically, “loss” suggests absence, but this loss of home and community has an ongoing emotional presence. (Field 2008: 115)

Losing one’s home is a deeply traumatic experience for all family members, including children. During the Second World War (henceforth WWII), hundreds of thousands of European families left their homes due to mass evacuations of civilians. This also happened in Finland while defending the borderlands against the massive armies of the neighboring Soviet Union. The major battlefields were located in the eastern and northern parts of the country. The residents of Lapland, the northern territory of Finland, left their homes twice: first in 1939 during the Winter War against the Soviet Union and again in 1944, due to the so-called Lapland War, a conflict between Finland and the former ally, Nazi Germany. Most Laplanders were eventually able to return to their home villages, but, in most cases, there were no homes left. Lapland, its villages, dwellings and infrastructure had suffered massive destruction by the German army, which, while retreating to northern Norway, applied “scorched earth tactics”.2 The German troops also booby-trapped the smoking ruins of villages and the roadsides with thousands of landmines. After the war ended, the evacuated civilians who returned to their homes had to begin their lives from scratch in the middle of hidden landmines and landscapes of utter destruction.3

One of the villages that suffered complete destruction was Vuotso, the southernmost reindeer-herding Sámi community in Finland, situated approximately 200 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle. It is known as the “Gate to Sápmi” (Sami poarta), the homeland of the Sámi, stretching across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.4 Vuotso has a surprising and little-known WWII history connected to the German presence in Finnish Lapland. The village, which at the outbreak of WWII had only eight households, hosted a major German supply base and a “resting house” (Rasthaus Vuotso), a military airport, and an anti-aircraft artillery base. The villagers of Vuotso interacted closely with the German and Finnish military and working troops who operated in the area, working for them, offering them accommodation, and trading everyday supplies. Toward the end of the war in 1944, the former friends became enemies, which resulted in a destruction that affected the lives of local people in profound ways for years to come.

This article examines the ways in which the Sámi elders of Vuotso recount their WWII experiences of war, evacuation, and the destruction of the village that was their childhood home, over seventy years after the war ended. During WWII, hundreds of thousands of children all over Europe witnessed violence and destruction. At the extreme, children were among the victims of mass destruction and bombing, and many of them met different forms of chaos and disruption in their everyday lives. These transformative experiences vary from losing a parent and experiencing forced displacement to suffering from lack of food. Children’s memories of WWII are not all tragic, but oftentimes full of excitement and adventure (see e.g. Schrumpf 2018). It is important to note that children experience the world differently than adults and are at the same time vulnerable, resilient, fragile and adventurous. Children’s spatial geographies and entanglements with nature and environment are formed through play and social interaction (see Moshenska 2008; Laakkonen 2011). They often perceive and remember minor details and things in their physical surroundings that adults do not pay attention to, and are attracted to disordered and dangerous places, such as bombsites and ruins, precisely because they fall outside of adult control and ordering (Cloke & Jones 2005; Moshenska 2014). During WWII and the post-war years, curiosity and adventurousness allowed the children to domesticate the new spaces – ruins, craters, burnt and deserted sites – in their local environment, due to warfare. Children explored the war sites despite parental warnings and prohibitions (see e.g. Moshenska 2014; Herva et al. 2016). It is important to acknowledge that the retrospective reminiscence of childhood experiences results in a mixture between children’s and adults’ perspectives: the narrated experiences are re-interpreted within the framework of later and present experiences and knowledge (Savolainen 2017). We ask: how do the elders remember and recount the experiences of war and its horrors that they faced as children? What kinds of nuances do their narratives entail and how do they challenge our understanding of WWII memory culture?

During the summers of 2015 and 2016, we visited the village of Vuotso four times together with our archaeologist colleagues as part of the research project Lapland’s Dark Heritage, through which we studied diverse cultural values and meanings of material heritage associated with the German military presence in northern Finland (Lapland) during WWII. We have used the concept of dark heritage to emphasize the difficult aspects of heritage that some groups may perceive as troublesome and painful in today’s perspective (e.g. Macdonald 2009; Jasinski, Neerland Soleim & Sem 2012). The darkness associated with WWII heritage refers to raised interest and fascination over death, war and other atrocities, noted and addressed in tourism studies (e.g. Stone 2006) that characterize some of the engagements with WWII heritage. Coined from the term difficult heritage, dark heritage acknowledges different attitudes toward WWII heritage, including silence on the one hand and interest on the other. The concepts of difficult and dark heritage can therefore give insights into a myriad of ways in which different groups of people and different generations approach WWII heritage (e.g. Koskinen-Koivisto 2016; Koskinen-Koivisto & Thomas 2018). We must also acknowledge that not everyone will find WWII heritage particularly dark, but will rather view it as a familiar, even mundane, element in local history (see Seitsonen 2018: 154).

The focus of the analysis is the narratives of four Vuotso elders5 who experienced the war, evacuation, and the destruction of their home village when they were still children or teenagers, and who grew into adults while reconstructing their homes. The post-war period was also characterized by the continued danger of unexploded ordnance (UXO): severe accidents continued to happen throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The focus of our interviews was on wartime experiences in general, but we also touched upon the times of post-war reconstruction and the treatment of material war heritage up until today.

The childhood narratives in the interviews include strong sensual and embodied elements, recognized as central in the expression of traumatic experiences (e.g. Moshenska 2014; De Nardi 2016: 97). These elements also evoked affective and embodied (Povrzanović Frykman 2016) responses in us – the listeners – that we seek to analyze, along with emotional content and non-verbal embodied expressions embedded in the narration and the process of recounting and working through the traumatic experiences of childhood. We thus aim to take into account the responsibility of the interviewer in the dialogic process of sharing, listening, and interpreting the narratives. Our research is informed by a post-colonial perspective that aims at recognizing asymmetrical power constellations and hierarchical modes of representation (e.g. Fischer-Tiné 2011). Our main aim is not, however, to analyze the historical wounds of the Finnish Sámi people of northern Finland, but to shed light on the complexity of experiences of children in times of conflict and the process of retrospective reminiscence and storytelling. It has been emphasized that during WWII, children in the Nordic countries took part in collective societal efforts, working along adults with various tasks at the home front, taking on new kinds of responsibilities (e.g. Schrumpf 2018). We seek to acknowledge these positive memories of the war period and ponder upon the different aspects of children’s experience.

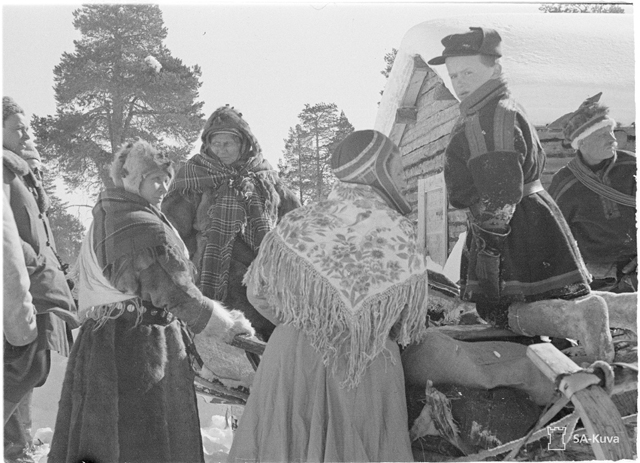

Wartime photograph from Vuotso. Original caption: “Lapps [sic] in Vuotso.” (Photographer unknown, SA-kuva, The Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive, 9926, April 14, 1940, http://sa-kuva.fi/webneologineng.html)

Memory Politics and Difficult Memories of WWII in Finnish Lapland

In our research, we approach individual memories as affected by collective memory culture(s), the ways of constructing, interpreting and representing a common past from the viewpoint of the present (e.g. Sääskilahti 2016). Instead of collective memory (e.g. Halbwachs 1992) that implies the existence of one collective mind or consensus, the concept of memory culture emphasizes that different interpretations occur simultaneously. At certain times, memory cultures of a given society or community may need to look away from difficult issues, so as to be able to function as a coherent whole and sustain co-existence (e.g. Connerton 2008; Seljamaa & Siim 2016: 6). These silences can occur, for example, in post-war societies that struggle with questions of ethnic or political unity and can be broken in order to negotiate conditions of cultural and societal change (Seljamaa & Siim 2016: 7).

In the context of WWII heritage, it is crucial to take account of the local and national, as well as the transnational memory cultures surrounding WWII and its aftermath (see also Sheftel & Zembrzycki 2010). In the context of Finland, the Vuotso elders’ narratives related to war and destruction are part of a neglected, unfinished, and ambivalent history of WWII. The complex history of Finland in WWII includes three conflicts, which are divided into three different wars: the Winter War (1939–1940) and the Continuation War (1941–1944), both fought between Finland and the Soviet Union, and the Lapland War (1944–1945) against Nazi Germany. The division has reinforced interpretations of separate conflicts emphasizing the narrative of national struggle for survival and downplaying the international connections (Meinander 2011). The first of the conflicts, the Winter War, has gained a special place in the national narrative that celebrates Finnish perseverance, which enabled small Finland to defend itself against the massive enemy, the neighboring colossus. This narrative is known as the miracle of the Winter War, and it tends to overshadow experiences related to later events, such as the experiences of the people in the north. The history related to the Continuation War, during which Finland allied with Nazi Germany, is more disputed,6 and later events such as the Lapland War and the destruction of Lapland have been marginalized (Raivo 2000: 157; Kivimäki 2012: 491; Kinnunen & Jokisipilä 2012: 436; Tuominen 2015). Over the years, public discussions have revolved around the Lapland War and its complicated role in Finnish history. On a national level, Finns have been anxious to distance themselves from the German war efforts ever since the war. Generally, the collaboration between the brothers-in-arms is depicted as a forced condition rather than an actual choice. As a result, Finland adopted a narrative of “the morally immaculate nation in a non-ideological war of self-defense,” as an essential and continuous element of the national imagery (Löfström 2011: 98; Meinander 2011). This has limited the ways in which the Finnish-German wartime alliance has been addressed, casting also a shadow of silence and shame over the everyday life experiences of wartime encounters with Germans (Tuominen 2015).

Lately, there has been criticism in both Norway and Finnish Lapland “of national histories based on northern-southern divide that erase the consequences of the Lapland War and the reconstruction period” (Lehtola 2015a: 126; see also Tuominen 2015).7 Furthermore, the national history of Finland has neglected the colonial past of Lapland and the Sámi (see Naum & Nordin 2013; Herva 2014; Lehtola 2015b).8 Studies on the effects on the Sámi community have only just begun. Sámi studies scholar Veli-Pekka Lehtola (2015a) has analyzed the effects of evacuation on Finnish Sámi communities based on extensive interview and archival material. According to him, WWII triggered large-scale changes in Finnish Sámi communities. One of the most important changes was a new kind of relationship with the Finnish language (Lehtola 2015a: 9). Until the evacuation of Lapland’s residents to southern Finland and Sweden before the Lapland War, many Sámi people from the remote areas did not speak Finnish, not to mention Swedish, which caused communication problems (Lehtola 2015a). Vuotso residents knew both Finnish and Sámi, as they lived in the borderland between the mostly Finnish-speaking municipality and Sápmi, the land of the Sámi. Despite this, their everyday lives, rhythm, food, clothes and spatial engagements were very different from the agrarian farm life of southern Ostrobothnia and Sweden, to which they were evacuated (see Seitsonen 2018: 165; Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018).

Narrating and Analyzing Children’s Memories of War and Conflict

As noted by many scholars, sensual and material approaches to memories and narration can give new insights into conflict experiences and also the processing of personal and collective trauma (Moshenska 2008, 2010, 2014; De Nardi 2016; Sääskilahti 2016; Povrzanović Frykman 2016). Childhood memories of conflict and post-conflict environments involve manifold sensual elements, kinesthetic choreographies, tactile engagements as well as detailed memories of smell and taste (see Moshenska 2014: 233–234; Povrzanović Frykman 2016). According to ethnologist Maja Povrzanović Frykman, who has studied Sarajevo residents’ experiences of humanitarian aid, sensory memories of conflict experiences are on the “edge of the ordinary”, an expression originally formulated by anthropologist Kathleen Stewart (2007). Through narrative memories related to smell and taste, Povrzanović Frykman’s interviewees described the rupture and disintegration of everyday life caused by warfare. She also reminds us that different generations may experience a conflict in different ways. When grownups understand and remember the danger, fear and helplessness, “children take the world around them – its materiality – as it is, as it unfolds for them through their senses” (2016: 96). Detailed sensual accounts are also rich in our material, in which the Sámi elders describe their childhood experiences of war.

We approach the Vuotso elders’ narratives of their childhood experiences as personal experience narratives: dramatic, truth-based accounts, which are positioned between reports of the everyday and that which disrupts ordinary life, and often told in the first person (see Shuman 2006; Marander-Eklund 2011). In considering tools for analyzing personal experience narratives, Lena Marander-Eklund (2011: 148) has pointed out that affective expressions as well as embodied and sensual elements of narratives such as laughter, humor, tone and rhythm of speech, and use of reported speech, are narrative keys, which build up the narrative tension. This tension is crucial in analyzing the layers of narrative interaction and meaning-making (see also Koskinen-Koivisto 2014: 48). It is important to note that narrative keys may appear in a non-verbalized form such as silence (e.g. Siim 2016), or sometimes suppressed and hidden within a seemingly neutral reporting style (see Kaivola-Bregenhøj 2006). The important aspect of these keys is that they affect and move the narrator as well as the listener, evoking affective responses. Exploring the affective connections between people and objects in the embodied memories of Sarajevo citizens at the time of the siege, Povrzanović Frykman (2016: 85) uses the term affective flashback to describe the intense moments of embodied authenticity appearing in the course of narration, which connect the past experience with the present moment, highlighting the intensity of the experience. According to her, some of the flashbacks are so intense that they appear as an absence of narration, as moments in which affect escapes the practices of a speaking subject (ibid.: 86). In our analytical process of repeated close-reading – or rather close-listening – of the interview material we paid attention to the narrative keys as well as potential affective flashbacks that appeared in the narratives/memories of the Sámi elders.

Our analysis of affective and embodied experiences of everyday life in the midst of a conflict as well as in a post-conflict environment illuminates the profoundness and ambivalence of children’s wartime experiences. The narratives of the elders who reminisce about their childhood are the last remaining keys to the lived experiences of WWII that continue to shape the collective mindscapes of Vuotso residents. They include nuances, from difficult and traumatic to ambivalent and even positive memories, that extend our understanding of the complexity of wartime experiences and the culture of commemoration of WWII in Finnish Lapland.

The Horrors and the Thrills of War – the Ambivalence of Childhood War-memories

Despite the emphasis on traumatic experiences of loss and destruction, we would like to point out that the Vuotso elders also told many good memories of wartime, especially of the Germans living in the village. The arrival of the brothers-in-arms in the village was exciting for the children, who gathered along the road to watch the endless convoy of German vehicles arriving in the remote village. Exploring children’s experiences of WWII through their own words (mainly letters, diaries and journals), Emmy E. Werner (2000) also found similar memories of thrill and excitement when witnessing the mobilization – fascination along with fear. Our interviewees characterized the Germans as friendly, emphasizing the neighborly relations between the villagers and the Germans. According to their narratives, the Germans treated the local children well, offering them food and goodies, and mostly ignoring their mischief and childish behavior (also discussed in Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018).

The other side of the war, actual human losses, horrors and fears of bombings and random attacks against civilians, was also familiar to the elders of Vuotso, who all characterize the era as fraught with constant fear. All the interviewees associate wartime mainly with the constant air raid warnings, especially after the Germans had established their military base and airfield in Vuotso, which the Soviet air force bombed almost daily:

The bombs came regularly, in a group of nine planes came, first three planes, then another three, and the rest. […] If in the morning one plane came that flew high, then we knew that at half past noon the bombing would begin. (Interview 2, Eila Magga)

The elders reported how their families spent much time sheltering in temporary kota-tent (traditional Sámi tent dwelling) camps outside the village and in the forest. One of the male interviewees, Oula Magga, remembers the fear they felt during the nights in the forest:

We were refugees. Sometimes we had to flee to the forest when we didn’t dare to sleep at home. It wasn’t much safer there. We just had to go, even in winter. It was scary, especially when our parents felt scared, too. (Interview 3, Oula Magga)

This is a good example of how war affected children’s daily lives, shaking the feeling of security and disrupting the everyday life rhythms and spatial bonds (Moshenska 2014; see also Kuusisto-Arponen & Savolainen 2016: 62–63). The notion of the adults’ fear is particularly powerful and painful, as children’s fear response in war is closely linked to the fear response of the adults around them (see Werner 2000). The same male interviewee stated that he could tell several stories of fleeing and hiding when the bombings began: once he hid in the huge oven of their multi-family one-room house and when the alarm was over he “crawled out from there like a black man” (Oula Magga). Some of his stories occurred in a form of almost funny anecdotes, entertaining and at the same time shocking. Such canonized war narratives seem to be typical for recounting WWII experiences in other European countries, such as Germany, where, at least in the 1980s and 1990s, people avoided stories about horrors and instead told entertaining anecdotes (see e.g. Rosenthal 1991; also Povrzanović Frykman 2016: 86). This can be interpreted as a way of externalizing and distancing oneself from personal traumatic experiences and collective guilt, and as a form of collective amnesia (ibid.; Welzer 2005). In this case, humor also seems to function as a narrative tool of an entertaining storytelling performance.

Another interviewee, Iisakki Magga, who was a small child during the war, said that one of his earliest memories is about bombing. He remembered hearing the loud noise of the aircraft and seeing clearly the colors and even the head of the pilot in one plane. He also recounted how one time as he stood on the doorstep he could hear how shells were dropping to the ground next to him. He decided to collect some as a secret memory of the war and kept them throughout the post-war years. In this narrative the sensual memory of “hearing the shells” is a narrative key that draws attention to the narrators’ affects, the feeling of fear that connects with the material and tactile memory of picking up a shell. Iisakki’s narrative with sensual and material details is an example of how children managed and overcame the harsh awareness of danger and death. Collecting war debris is typical for children in conflict areas and serves different purposes, some of which are therapeutic. For children who live in the middle of a chaotic and dangerous reality in which not even adults have full control over what happens, collecting can represent a way of establishing some – at least an illusory degree of – control, integration, and ownership in their everyday lives (see e.g. Moshenska 2008).

The memories of bombing experienced in childhood seem to be as fresh and clear as if they had happened yesterday. Our female interviewee Eila Magga, who was about twelve years old when Soviet bombings occurred daily, recounted an embodied bombing experience:

Once I was home alone and a cousin of mine came to pick me up saying that I should not be alone if the bombing begins. I put on my nicer Lapland outfit [Sámi costume] and went with her, but on the way the bombing began and we ran behind a big pine tree across the road. We dug a space deep into the snow. My cousin cried and I was more scared than ever. When the bombing ended, we could not get out of the snow because the pine tree was hit and all the branches fell upon our snow shed. We were all snowy and covered with pine needles from head to toe. I had pine needles stuck in my hair for days. When we finally dug our way out, I told my cousin that I needed to go home to see if my mom is ok. So I ran to the barn to find my mom who was very worried when she could not find us. We told her that we had dug into the snow and [whispers] that it was horrible. (Interview 2, Eila Magga)

Eila’s narratives of hiding do not contain almost any typical narrative keys such as emotional expressions, laughter or silence. However, the fear and horror becomes obvious as she describes her mother’s reaction to the situation. At the end of the narrative, her voice changes into whisper when she describes telling her mother about what had happened. Eila also remembers that after this occasion, her father dug shelters in the snow under the rowing boats that during winter were stored on the riverbank by their uncle’s house.

The reminiscences of bombings like those above often involve strong sensual and embodied memories. As mentioned, for the children of the WWII who experienced bombing, the vivid memories often include smell and sound as well as visions, which in some cases remain painful throughout their lives (Moshenska 2014: 234; 2016). In Eila’s narrative above, the experience of extreme fear and mortal danger is embodied in tactile and kinesthetic memory of being entombed in the snow. Interestingly, she also mentions the detail of having dressed up nicely in the traditional colorful Lapland (Sámi) costume. This vivid detail communicates that the close hit of a bomb came as a surprise, turning the threat real. In narrating such intense moments of fear, the details of colors and other sensations come back to life, and the surrounding details of objects, places, and their locations are described in detail.9 Although it does not seem that the Vuotso elders we interviewed would have suppressed their memories of war, but instead have recounted them in the village at least since the 1960s, the collective memory of Vuotso residents does involve chapters that still represent an open wound and are expressed only through moments of silence. Among the deeply traumatic collective memories of the residents of Vuotso are the stories of Soviet partisan attacks. Groups of Soviet partisans roamed in the wilderness of eastern Lapland throughout WWII, attacking isolated homesteads and killing civilians, including young children (Magga 2010). These attacks, virtually ignored until the collapse of the Soviet Union, claimed the lives of nearly 200 Finnish civilians between 1941–1944 (Martikainen 2011; Tuominen 2015).

During our research, we found that one of the interviewees had lost close family members in a partisan attack in which only a few children had survived. After we had discussed his memories of the Germans in the village, the 85-year-old male interviewee Maunu Hetta told us in detail a story of how his elder sister and her two children died in a partisan attack by Russians. The tragic story about the murders is exemplified with the survival of the other children, two small girls (i.e. Maunu’s nieces), who were advised to hide in the barn by a Sámi man who worked as a farmhand for Maunu’s sister’s family when her husband was away in the war. The man had fought on the front himself and had recently returned. He had already noticed the Russian partisans earlier when he was picking cloudberries in a nearby wetland. When they came to the house where the young mother stayed with her four children and her mother-in-law, they asked them in Finnish to open the door. The Sámi man saw no danger and opened the door. The partisans threatened the man with a gun, and, realizing the danger, he spoke in his own Sámi language to the two small children who were with him, telling them to hide in the barn:

There was a Finnish-speaking woman among the partisans who told the girls to get dressed and wait in the yard. But the girls did not follow this order. Instead, they followed the man’s advice [given in Sámi] and hid in the barn. (Interview 4, Maunu Hetta)

Maunu continued the story by calmly describing how the partisans went into the bedroom and killed the sleeping two-month-old baby and his two-year-old brother by stabbing them with bayonets and shot their mother who tried to escape through the window. The girls were not found and became the only survivors from the farmstead. After wandering to the neighboring house where the partisans had also been and killed the inhabitants, they went into hiding again, and were eventually found by their father who was among the Finnish anti-partisan troops. One of them is still alive, but both were badly traumatized for life by this horrific experience.

Maunu calmly recounted every detail and paused regularly to wait for us to make our notes and receive what he was telling us. His calmness made an impression on us, the interviewers, and after hearing the horrifying story, we fell completely silent. It seemed the only appropriate reaction to the situation, through which we could respect and consider what he had said. When one of us researchers, Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto, later listened to the tape, she realized that the long silence worked as a dialogue between us, the researchers and the narrator, forming a language of experience that goes beyond words (see also Kaivola-Bregenhøj 2006). This skill of falling into and listening to the silence is especially important when studying traumatic experiences and memories (Siim 2016: 77). In these moments, our role as scholars or experts became secondary, and the role as fellow human beings and citizens primary (for more on the critique of empathy, see Shuman 2006). In the aforementioned narrative, the role and use of the Sámi language is crucial: it functions as a language of resistance and escape that enabled the Sámi man and the two nieces to communicate in secret thus challenging the subordinate position (Spivak 1988) of the Sámi. During the WWII the Sámi were in-between the varying interests of many perpetrators and colonizers, including the German Army, the Finnish Defense Forces, and the enemy across the border, the Soviets, who in 1944, took possession of some of the Sámi lands. In the end, the Sámi were subordinate to all these outsider forces, and could only rely on each other. This sense of togetherness of the Sámi is emphasized in all the elders’ childhood narratives of the different stages of the war. It is even more exemplified in the narratives related to evacuation and displacement.

Memories of Evacuation and Displacement

Stories of evacuation and longing for the lost home have a special role in the national WWII narrative, especially in the case of the evacuation and resettlement of the Karelians from the ceded parts of south-eastern Finland (e.g. Kuusisto-Arponen 2009; Fingerroos 2012; Korjonen-Kuusipuro & Kuusisto-Arponen 2012: 110). The harrowing experiences of the evacuation and destruction of Lapland have received significantly less public and scholarly attention, and it has been claimed that for various reasons they are not part of the cultural trauma of the Finns (Sääskilahti 2013).10 The destruction and reconstruction of Lapland allowed the central government better access to the area, and it could be argued that the events of WWII accelerated new forms of colonization and exploitation of the northern resources and assimilation of Sámi culture (Lehtola 2015a, 2015b).

The evacuation of Lapland took place in September 1944. When the Finnish-German alliance came to an end in autumn 1944, the treaty between the Soviet Union and Finland demanded that German troops be expelled from the country within two weeks. This was obviously an unrealistic timetable considering the number of German troops, the extent of their military installations and the amount of equipment they hauled. During the first weeks after the Finnish headquarters issued the evacuation order, the Finns and the Germans worked together to move the civilians southwards to the northernmost railway station of Rovaniemi (the capital of Lapland) through which most of the evacuees were moved to different parts of Finland, mainly northern Ostrobothnia (Tuominen 2015). Those who had a chance settled with their relatives, but most families spent the first weeks in schools and other public buildings that were turned into temporary dwellings. Later, most families were relocated to individual households across the Ostrobothnian countryside. Many Sámi families were split up: some older girls and unmarried young women walked the dairy cattle across the border to northern Sweden while some young men of reindeer-herding families stayed in the fells to protect their reindeer (Lehtola 2015a).

Despite the generally friendly atmosphere between German soldiers and Finnish civilians in Lapland still in fall 1944, the situation in the beginning of the evacuation journey was chaotic: the evacuees had no idea about how far they needed to go and how long they should stay, or if they would ever be able to return to their homes. Again, the elders of Vuotso underline how they as children did not fully understand the gravity of the situation: in their eyes, the evacuation journey was exciting. Eila, for example, told us how she wondered why her mother cried at the scene because she could only think it was a great adventure. Only after growing up and establishing her own life and family in Vuotso did she understand her mother’s emotions at abandoning a home that the family members had built by hand and the place where her children were born (Interview 2, Eila Magga).

Despite the detailed descriptions of the moment of leaving the village in haste and the immediate evacuation journey in the backs of German military trucks and overcrowded trains, our interviewees had hardly anything to tell about the time they spent away from Vuotso (see Seitsonen 2018: 51). Kuusisto-Arponen and Savolainen (2016) have also noted the scarcity of displaced children’s descriptions of their temporary shelters and the new surroundings compared to the detailed memories of their home environments before the evacuation. For the inhabitants of the Lapland wilderness, the deportation to flat Ostrobothnian farmlands or Swedish refugee camps was a strange experience. The foreign landscapes work as a metaphor for the profoundness of the experience of being displaced – away from home and the home village, particular ways of life, culture and traditions (see also Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018; Seitsonen, Herva & Kunnari 2017). Reminiscing about their time in the south, the three men whom we interviewed compared the murky rivers of Ostrobothnia and the flat clay fields with Lapland’s clear streams and the dramatic landscapes of towering fells and vast forests (also Lehtola 2015a; Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018).

The Vuotso people, however, felt lucky to be stationed in adjacent villages in Ostrobothnia, where they could keep in contact with their relatives. This was especially important to Maunu, who had already lost his mother in his early childhood and whose sister and nieces were killed in the partisan attack. Unfortunately, the tragedies in his family continued, as Maunu’s father, like many other Sámi, fell ill on the evacuation journey, and finally died when they reached their temporary settlement in Ostrobothnia. Maunu told us how he accompanied his father to the hospital and met somebody from their village:

My father fell ill when we were staying in a school. It was very cold there when we put a fire on the stove in there and then soon very cold again. He was still ill when we arrived at the village of Karhi. They told a farmhand that he should take us to hospital right away. So I went with them. We went to hospital and I met a man there from our region. This man recognized me, and he told me that he could take me to his relatives and I could stay with them overnight. So I stayed with them and in the morning I saw him again in the yard and asked him how my father was doing. He didn’t say anything, just told me to go to see the nurses. Finally, I heard from the nurses that my father had died during the night. (Interview 4, Maunu Hetta)

After reporting the tragic course of events, Maunu fell silent. He did not continue until we, after a long moment of silence, spoke and expressed our condolences. When we wondered how he felt as a young boy, he admitted that he felt terrible. He recounted how his father was buried in Ostrobothnia, far away from home, and the siblings who were placed in different locations had to continue their lives as orphans. Maunu had two older brothers, one who was in the fells with the reindeer and another who was with Maunu in northern Ostrobothnia, and a sister who had been evacuated with the family’s cows to Sweden. The sister stayed in Sweden and married a Swede. The two brothers returned to the village along with other villagers and, together with their elder brother, began to rebuild their homestead. Maunu did not tell us about their sorrow, coping or survival. He just mentioned that their reindeer, their most valuable property that constituted the Vuotso families’ livelihood in the pre-war years, had survived because some male youngsters had stayed with them in the fells throughout the Lapland War. However, the other interviewees described how the extended family, aunts and uncles, looked after these orphaned boys whose fate touched everybody in the village. Especially one of the aunts, Eila’s mother, had cared for Maunu, offering him food and motherly support. Decades later, when Eila lost her husband and became a widow, Maunu helped her with everyday tasks such as shoveling snow; he still felt grateful to Eila’s family for their support during and after the war.

Maunu was not the only one among our interviewees who had lost both parents at a young age. Eila told us about the struggle to rebuild her family home, the scarcity of materials and long hours of work together with her parents. After staying in temporary settlements, first in a log-built sauna and later in one end of a building that also housed a school and the village shop, the family was able to move into their own new house on the last day of December 1948. Shortly after, her mother fell ill and died. According to Eila, her mother was traumatized from the two evacuations she had experienced. The combination of physical illness, homesickness caused by the sudden and chaotic evacuation experience, and the tragedies happening around her were too hard on her heart. When her mother died, Eila was sixteen years old and as the oldest female in the house the responsibilities of the household fell on her: cooking, cleaning, and laundry, as well as caring for her younger siblings. Maunu’s and Eila’s stories underline the difficult circumstances for the Sámi villagers of Vuotso after WWII. Needless to say, wartime suffering and shared feelings of loss tightened the relations between the Vuotso villagers. As Eila herself states, despite all that they experienced during and after WWII, they have survived and continue to reside in their beloved village.

Landscapes of Loss and Destruction

The evacuees of Lapland started arriving back in their homeland as soon as the war was over, but due to the destruction of infrastructure, railroads, bridges and electricity, as well as severe danger of landmines on the roadsides and in the remaining dwellings of the villages, the journeys back were difficult and slow, and in many areas possible only on water. The first (male) reindeer herders drifted northwards while the fighting continued, arriving in Vuotso in November 1944. Later, in spring 1945, other family members including children followed. Our interviewees were among them. Returning to the village, they had to face a desolate sight: nothing had been spared. As reindeer herder Iisakki Magga (age 75) put it, “not even a dog house survived, not a telephone pole, nothing. Germans are precise” (Interview 1, Iisakki Magga). This is the only statement by our interviewees against the Germans that has a hint of bitterness.

The Vuotso elders all mentioned a twofold feeling of shock and joy when returning to a demolished homeland. Throughout the autumn and winter spent in Ostrobothnia the evacuees had felt home-sick, and catching the first glimpses of familiar landscapes, such as the iconic – and for the Sámi holy – Nattaset fells next to Vuotso, raised feelings of hope and comfort. They emphasized that despite the dramatic loss of human lives and material property, what mattered most was that they still had their own lands, and at least some reindeer.11

The elders also recounted a narrative of how, to their surprise, the first arrivals who returned from their evacuation journey to Vuotso found seven hidden, dismantled German plywood tents with functioning stoves next to their old forest campsite near the village. According to the elders, the tents functioned as the first shelter for the families who returned to Vuotso during the spring and summer of 1945. They interpreted this as a last friendly act from their former German brothers-in-arms, who in their view chose to provide the villagers with shelter on their return (see also Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018). True or not, this story of “our Germans” who are believed to be others than those who set the village on fire is commonly told all over Lapland (e.g. Lehtola 2015a). This shared narrative can be interpreted as part of the on-going collective process of coming to terms with a difficult past. The attempt to find even the slightest sign of “fragile goodness”, a concept created by the Bulgarian philosopher Todorov and discussed by the Finnish oral historian Ulla-Maija Peltonen (2012), who has studied the memory culture of the Finnish Civil War of 1918, is an attempt at humanizing not only the enemy, but also the war itself. This tendency to see something good in extreme situations, like the complete destruction of the home village by former brothers-in-arms, offers a point of reference on which one can build the future.

As the conflict archaeologist Gabriel Moshenska (2014: 236), who works with place-based memories, reminds us, the post-conflict sites are places in transition. After the first dramatic transition making the ordered place disordered, and a lived-in place an empty ruin, there is a set of transformations, from rescuing and clearing the site to reconstruction and/or ecological transformation. The mental process related to transformed geographies entails a disrupted sense of place and longing, as well as new habitual spatial routines, a reclaiming of the places. The return to the home and the continuation of everyday life was both dangerous and challenging for the Vuotso villagers. During their retreat, the Germans laid hundreds of thousands of landmines and other explosives in the landscape, which claimed hundreds of lives after the war. Most of the villagers returned in the spring and summer of 1945 after the military had de-mined the main roads, and the men had prepared rudimentary accommodation for their families, typically log-built saunas. All the interviewees reminisced about how children actively participated in the building efforts and in salvaging material from the ruins. They, especially the young boys, also engaged in dangerous and prohibited activities such as playing with UXO that they found. One of the interviewees, Iisakki, told us that the men directed them on how to handle various explosives, but accidents were unavoidable in this dangerous game: one of the village boys was killed as late as in 1959 and several others were injured (also Magga 2010; Seitsonen 2018: 124–125).

In the summer of 2016, Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto visited Vuotso and the site where the young boy was killed together with Iisakki Magga, whose older brother (who passed away some years ago) was present on the scene and later raised a memorial of flat stones in the form of a cross there (see Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018). She wrote in her field diary about the visit:

When I asked him if we could see the site, Iisakki told me that he had not visited there for over fifteen years. The visit was meaningful not only for the two of us, but also for the dead boy’s family and the whole village community. When we came back from the site and went together to the meeting place of the village, to the coffee tables of the small grocery store, people joined us and talked with us. An old man came to shake my hand and told me that it was his brother who died there. After him, three other younger brothers joined us. I learned that there were altogether nine of them, of whom seven are still alive. Iisakki told the brothers where we had been. There was a complete silence in the shop. We all looked at the ground and could not speak a word for a long time. Finally, the three brothers told me that they had never visited the place because they were strictly prohibited from going to the area, which still has plenty of ammunition everywhere. Without saying a word, the four brothers and Iisakki left the shop to go and to see the memorial.

This encounter between Eerika and the villagers made visible the collective process of recovery, which is still going on in the community. The process entails different acts of commemoration, such as revisiting and sharing of childhood memories with community members, scholars, and younger generations like schoolchildren, as well as introducing and visiting the sites of dark heritage. What is essential in these encounters is that they bring about a nuanced picture of the war and post-war experience that along with traumatic chapters include ambivalent and positive memories. To acknowledge this complexity of conflict experience is an essential part of coming to terms with a difficult past.

Conclusions

The Lapland War had profound effects on the lives of its residents, especially the indigenous Sámi. In Vuotso, the Sámi children encountered the complexity and tragedy of this warfare that in the post-war years has represented a challenge to the local (and national) memory culture of processing personal and collective traumas. The narratives of the Vuotso Sámi elders about their childhood during and after WWII shed light on the ways in which children experienced the rupture of everyday life that their community faced. Among the most traumatic experiences were those that disrupted everyday life and the feeling of security. During the wartime and post-war years, the interviewees’ community witnessed, among other tragedies, a random partisan attack, post-war landmines and UXO accidents that had taken lives of ordinary civilians. One of our interviewees lost both parents on the evacuation journey. In this text, we analyzed the articulations of these traumatic experiences applying sensual and material approaches to childhood memories of WWII. In the process, our attention was drawn to the intensity of ephemeral experiences of childhood, thus revealing controversies and ambivalences of the perspective of innocent, sometimes fearless and naïve children. The interviewees told us how, in some cases, they realized how dangerous and threatening situations were, such as heavy bombings. In other cases, they experienced incidents such as the evacuation journey as an exciting adventure (also Schrumpf 2018). From an adult’s perspective, the evacuation journey(s) and loss of home, for example, were only chaotic, tragic, and traumatic. These nuances and ambivalences are simultaneously present in retrospective reminiscence, when the narrator reflects on the past from various perspectives, that of a child and that of an adult or a parent.

In the Sámi elders’ memories, children’s war experiences were rendered into words and articulated through sensory and embodied details of voices, silence, and touch. Some narratives were told in a seemingly detached reporting style. In some cases, distance, and even humor is needed in encountering the trauma and continuing life (also Povrzanović Frykman 2016). The ability of seeing things in a positive light was striking in the Sámi elders’ memories of WWII. Despite the complete destruction of the dwellings and infrastructure in their home village, the return to the destroyed village was remembered as a happy moment: being back at home meant being back in their ancestors’ landscapes, in the familiar surroundings of forest and fells. The detail of the remaining plywood tents found in the village by the first evacuees who returned was interpreted by the interviewees as a sign of goodwill on the part of the Germans, the former friends and allies, who are still thought of mostly as a positive memory. This tendency challenges the national narrative of WWII in Finland that sees the Finns as victims who defended themselves against hostile foreign forces.

The experiences and articulations of loss, but also hope, which is present in the narratives of the Sámi elders of their childhood memories, have added nuances to the ways in which WWII events of Finnish Lapland, especially those connected to the presence of German troops and the destruction that they caused during the Lapland War, are remembered. For the Vuotso Sámi elders, WWII history and heritage are not as dark as it may seem at first, but rather an essential part of their personal and collective history. The conflict and its aftermaths caused personal tragedies in their lives, but also strengthened their sense of belonging to their ancestors’ land and of being unified with their fellow villagers. For them, it is important that their experiences, both traumatic and ambivalent, are included among the national and global assemblages of the narratives of WWII, and not labelled as part of a difficult or dark heritage forced on them from the outside.

Notes

- The Cultural Foundation of Finland and Academy of Finland (decision number 275497) have funded this research. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the American Folklore Society’s joint meeting with International Society of Folk Narrative Research “Unfinished Stories” in Miami, Florida, 2016 by Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto. We would like to thank all the participants of the panel entitled Contested Histories and Narratives. Special thanks go to the discussant of the panel Professor Amy Shuman. We would also like to thank Dr. Gabriel Moshenska for helping us forward with the text. [^]

- Before the outbreak of the Finno-German “Lapland War” in September 1944, 100,000 civilians of the provinces of Lapland and Oulu were evacuated. So-called scorched earth tactics meant that the withdrawing troops destroyed not only their military installations but also the local civilian infrastructure, buildings and dwellings, including bridges, railroads, telephone poles and culverts, and barn houses, by setting them on fire or using the ammunition. An estimated 90% of the settlements in the worst affected areas were destroyed, which caused the vanishing of local architecture and ways of life (Tuominen 2005). [^]

- Unlike in most of the research about WWII experiences, we use the term “evacuees” instead of refugees when referring to the residents of the evacuated areas of Finland. In the Finnish context of WWII, the term is mostly associated with Karelians who lived in the south-eastern parts of Finland that were ceded to the Soviet Union in the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1944. Approximately 400,000 Karelians were permanently resettled in different parts of Finland. According to researchers of the memory culture of WWII, the loss of Karelia is a national trauma that has resulted in nostalgic and utopic visions (e.g. Korjonen-Kuusipuro & Kuusisto-Arponen 2012). [^]

- Vuotso is the second largest village in the municipality of Sodankylä, with about 350 inhabitants and its own school. The number of residents is significantly higher than in wartime; people from the nearby villages of Lokka and Mutenia were in the 1950s and 1960s forced to move due to the construction of large reservoir lakes in the vicinity (Väyrynen 2012). [^]

- We interviewed the elders individually in August 2015 at the local bed and breakfast Vuotson maja. The interviews were arranged by an elderly woman, a history hobbyist who moved to the village from outside of the area and has taken interest to the region’s war history (see Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2018). The interviewees were born in 1930–1939. One of them is female, and the other three are male. Unlike in our former studies, in this article we introduce them by their full names. In the context of de-colonialization and the politics of recognition, we decided to emphasize the narrators’ ownership of the stories. Not only the interviewees themselves but also other members of their families and community want the Sámi elders’ voices to be heard and their experiences acknowledged among a wider audience, especially by the people of southern Finland, who are often unaware – or ignorant – of the destinies of the people in the north. Furthermore, the narratives we analyze are very personal and include details that make the interviewees easily recognized. The interviewees have given us permission to use their names as well as to share photos of our encounters. All of them had prior experiences of being interviewed for a book project on the history of the local Vuotso Sámi community using their own names (Aikio-Puoskari & Magga 2010). After the first interview, Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto visited the homes of two of the interviewees and met the other two informants at the coffee corner of the local village store in 2016, giving them (and their families) a copy of the interview tape. [^]

- The Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union resulted in Finland’s territorial losses, and during the following so-called Interim Peace Period, Finns were afraid of a new attack. In 1941, Finland allied with Nazi Germany to ensure military aid and in hopes of a chance to reclaim the ceded areas. The collaboration between Finland and Germany focused especially on northern Finland where the German troops came to operate preparing for the attack on the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa. Over 200,000 German soldiers and service troops consisting of mostly German and Austrian nationals were based in the northern parts of Finland. The Finnish army and many civilian workers co-operated with Germans to build large military bases, for instance in the capital of Lapland, Rovaniemi, and other northern towns, and many other locations. [^]

- Northern Norway experienced a similar kind of destruction and mass-evacuation as northern Finland when the German occupation ended and the German army withdrew from the area of Finnmark. Experiences of the people of the north have also been neglected and silenced in Norway. [^]

- Researcher of Finnish Sámi cultures and histories Veli-Pekka Lehtola (2015b) defines colonialism as a condition under which fundamental decisions affecting the lives of the colonized people are made by the colonial rulers who act according to their own interests. In this light, the Sámi of Lapland have been colonized by the Finnish State; attempts to regulate the Sámi mobility and settlement as well as exploitation of resources have taken place in the north since the seventeenth century. In order to benefit from the economic resources of the northern territories, the state authorities took possession of the Sámi lands especially from the 1890s and onwards. In addition, Christianity and the embedded education systems reinforced the “colonization of minds”. Like other Nordic countries, Finland has not fully acknowledged its colonial legacy (Naum & Nordin 2013; Herva 2014; Lehtola 2015b), and issues concerning land ownership and land-use continue to appear. [^]

- These so-called flashbulb or vivid memories (e.g. Pillemer 1998) are like snapshots, imbued with feeling, sensual perceptions and bodily sensations that often occur unwillingly and appear in dreams. [^]

- There is an emphasis in the national narrative on collective survival, which subdues personal and emotional narratives of loss (see Korjonen-Kuusipuro & Kuusisto-Arponen 2012: 119). In addition, the witnesses have not transmitted the memories of loss and destruction, and despite memory production at local level, greater public interest has only recently arisen (see Sääskilahti 2013). Thus, it can be argued that the memory work around this difficult experience is a very much unfinished and on-going process. [^]

- In the poorest position were evacuees from the Petsamo, Salla and Kuusamo regions, which were ceded to the Soviet Union. Whole ways of life were shattered when people lost their ancestral lands. This was the case for especially the semi-nomadic Skolt Sámi; some of them lived for years in temporary shelters, in lingering uncertainty, until finally being relocated in the 1950s (e.g. Lehtola 2015a, 2015b). [^]

Interviews

Interview 1: Iisakki Magga born in 1939. August 10, 2015. Vuotso. Interviewers Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto, Oula Seitsonen and Vesa-Pekka Herva.

Interview 2: Eila Magga, born in 1931. August 10, 2015. Vuotso. Interviewers Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto and Oula Seitsonen.

Interview 3: Oula Magga, born in 1934. August 11, 2015. Vuotso. Interviewers Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto and Oula Seitsonen.

Interview 4: Maunu Hetta, born in 1930. August 11, 2015. Vuotso. Interviewers Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto and Oula Seitsonen.

Literature

Aikio-Puoskari, Ulla & Päivi Magga 2010: Kylä kulttuurien risteyksessä: Artikkelikokoelma Vuotson saameleisista. Vuotso: Vuohču Sámiid searvi.

Cloke, Paul & Owain Jones 2005: “Unclaimed Territory”: Childhood and Disordered Space(s). Social and Cultural Geography 6:3, 311–333.

Connerton, Paul 2008: Seven Types of Forgetting. Memory Studies 1:1, 59–71. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1750698007083889

De Nardi, Sarah 2016: The Poetics of Conflict Experience: Materiality and Embodiment in Second World War Italy. London & New York: Routledge.

Field, Sean 2008: Imagining Communities: Memory, Loss, and Resilience in Post-Apartheid Cape Town. In: Paula Hamilton & Linda Shopes (eds.), Oral History and Public Memories. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, pp. 107–124.

Fingerroos, Outi 2012: “Karelia Issue” – The Politics and Memory of Karelia in Finland. In: Tiina Kinnunen & Ville Kivimäki (eds.), Finland in World War II: History, Memory, Interpretations. Leiden & Boston: Brill, pp. 483–518.

Fischer-Tiné, Harald 2011: Postcolonial Studies. European History Online. Mainz: Institute of European History (IEG). December 3, 2010, http://www.ieg-ego.eu/fischertineh-2010-en. Accessed March 9, 2018.

Halbwachs, Maurice 1992: On Collective Memory. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Herva, Vesa-Pekka 2014: Haunting Heritage in an Enchanted Land: Magic, Materiality and Second World War German Material Heritage in Finnish Lapland. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 1:2, 297–321. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1558/jca.v1i2.18639

Herva, Vesa-Pekka, Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto, Oula Seitsonen & Suzie Thomas 2016: “I have better stuff at home”: Treasure Hunting and Private Collecting of World War II Artefacts in Finnish Lapland. World Archaeology 48:2, 267–281. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2016.1184586

Jasinski, Marek E., Marianne Neerland Soleim & Leiv Sem 2012: “Painful Heritage”. Cultural Landscape of the Second World War in Norway: A New Approach. In: Ranghild Berge, Marek E. Jasinski & Kalle Sognnes (eds.), N-TAG TEN: Proceedings of the 10th Nordic TAG Conference at Stiklestad, Norway 2009. BAR International Series 2399. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 263–273.

Kaivola-Bregenhøj, Annikki 2006: War as a Turning Point in Life. In: Annikki Kaivola-Bregenhøj, Barbro Klein & Ulf Palmenfelt (eds.), Narrating, Doing, Experiencing: Nordic Folkloristic Perspectives. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, pp. 29–46.

Kinnunen, Tiina & Markku Jokisipilä 2012: Shifting Images of “Our” Wars: Finnish Memory Culture of World War II. In: Tiina Kinnunen & Ville Kivimäki (eds.), Finland in World War II: History, Memory, Interpretations. Leiden & Boston: Brill, pp. 435–482.

Kivimäki, Ville 2012: Between Defeat and Victory: Finnish Memory Culture of the Second World War. Scandinavian Journal of History 37:4, 482–504. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2012.680178

Korjonen-Kuusipuro, Kristiina & Anna-Kaisa Kuusisto-Arponen 2012: Emotional Silences: The Rituals of Remembering the Finnish Karelia. In: Barbara Törnquist-Plewa & Niklas Bernsand (eds.), Painful Pasts and Useful Memories: Remembering and Forgetting in Europe. CFE Conference Papers Series 5. Lund: Centre for European Studies, pp. 109–126.

Koskinen-Koivisto, Eerika 2014: Her Own Worth – Negotiation of Subjectivity in the Life Narrative of a Female Labourer. Studia Fennica Ethnologica 16. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Koskinen-Koivisto, Eerika 2016: Reminder of Dark Heritage of Humankind – Experiences of Finnish Cemetery Tourists of Visiting the Norvajärvi German Cemetery. Thanatos 5:1, 24–41.

Koskinen-Koivisto, Eerika & Suzie Thomas 2018: Remembering and Forgetting, Discovering and Cherishing: Engagements with Material Culture of War in Finnish Lapland. Ethnologia Fennica 44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.23991/ef.v45i0.60647

Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa 2009: The Mobilities of Forced Displacement: Commemorating Karelian Evacuation in Finland. Social and Cultural Geography 10:5, 545–563. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14649360902974464

Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa & Ulla Savolainen 2016: The Interplay of Memory and Matter: Narratives of former Finnish Karelian Child Evacuees. Oral History 44:2, 59–68.

Laakkonen, Simo 2011: Asphalt Kids and the Matrix City: Reminiscences of Children’s Urban Environmental History. Urban History 38:2, 301–323. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926811000423

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka 2015a: Second World War as a Trigger for Transcultural Changes among Sámi People in Finland. Acta Borealia 32:2, 125–147. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/08003831.2015.1089673

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka 2015b: Sámi Histories, Colonialism, and Finland. Arctic Anthropology 52:2, 22–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3368/aa.52.2.22

Löfström, Jan 2011: Historical Apologies as Acts of Symbolic Inclusion – and Exclusion? Reflections on Institutional Apologies as Politics of Cultural Citizenship. Citizenship Studies 15:1, 93–108. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2011.534933

Macdonald, Sharon 2009: Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi Past in Nuremberg and Beyond. London: Routledge.

Magga, Aini 2010: “Elämää sotavuosina”. In: Ulla Aikio-Puoskari & Päivi Magga (eds.), Kylä kulttuurien risteyksessä: Artikkelikokoelma Vuotson saameleisista. Vuotso: Vuohču Sámiid Searvi, pp. 64–79.

Marander-Eklund, Lena 2011: Livet som hemmafru. In: Lena Marander-Eklund & Ann-Catrin Östman (eds.), Biografiska betydelser: Norm och erfarenhet i levnadsberättelser. Möklinta: Gidlunds förlag, pp. 133–156.

Martikainen, Tyyne 2011: Chimney Forests. Kuosku, Magga, Seitajärvi, and Lokka: The Destruction of Four Villages in Finnish Lapland. St. Cloud: North Star Press.

Meinander, Henrik 2011: A Separate Story? Interpretations of Finland in the Second World War. In: Henrik Stenius, Mirja Österberg & Johan Östling (eds.), National Historiographies Revisited: Nordic Narratives of the Second World War. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 55–77.

Moshenska, Gabriel 2008: A Hard Rain: Children’s Shrapnel Collections in the Second World War. Journal of Material Culture 13:1, 107–125. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1359183507086221

Moshenska, Gabriel 2010: Gas Masks: Material Culture, Memory, and the Senses. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16, 609–628. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01642.x

Moshenska, Gabriel 2014: Children in Ruins: Bombsites as Playgrounds in Second World War Britain. In: Þóra Pétursdóttir & Bjørnar Olsen (eds.), Ruin Memories: Materiality, Aesthetics and the Archaeology of the Recent Past. London & New York: Routledge, pp. 230–249.

Moshenska, Gabriel 2016: Moaning Minnie and the Doodlebugs: Soundscapes of Airfare in Second World War Britain. In: Nicholas J. Saunders & Paul Cornish (eds.), Modern Conflict and the Senses. London & New York: Routledge, pp. 106–122.

Naum, Magdalena & Jonas M. Nordin 2013: Introduction: Situating Scandinavian Colonialism. In: Magdalena Naum & Jonas M. Nordin (eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: Small-Time Agents in a Global Arena. New York: Springer, pp. 3–16.

Peltonen, Ulla-Maija 2012: Hauras hyvyys ja anteeksianto sodan muistoissa. In: Jan Löfström (ed.), Voiko historiaa hyvittää? Historiallisten vääryyksien korjaaminen ja anteeksiantaminen. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, pp. 118–135.

Pillemer, David B. 1998: Momentous Events, Vivid Memories. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Povrzanović Frykman, Maja 2016: Sensitive Objects of Humanitarian Aid Corporeal Memories and Affective Continuities. In: Jonas Frykman & Maja Povrzanović Frykman (eds.), Sensitive Objects Affect and Material Culture. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 79–104. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21525/kriterium.6.d

Raivo, Petri 2000: “This is where they fought”: Finnish War Landscapes as a National Heritage. In: Timothy G. Ashplant, Graham Dawson & Michael Roper (eds.), The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration. London: Routledge, pp. 145–164.

Rosenthal, Gabriele 1991: German War Memories: Narrability and the Biographical and Social Functions of Remembering. Oral History 19:2, 34–41.

Sääskilahti, Nina 2013: Ruptures and Returns: From Loss of Memory to the Memory of Loss. Ethnologia Fennica 40, 40–53.

Sääskilahti, Nina 2016: Konfliktinjälkeiset kulttuuriympäristöt, muisti ja materiaalisuus. Tahiti: taidehistoria tieteenä 1, http://tahiti.fi/01-2016/. Accessed February 2, 2017.

Savolainen, Ulla 2017: The Return: Intertextuality of the Reminiscing of Karelian Evacuees in Finland. Journal of American Folklore 130:516, 166–192. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5406/jamerfolk.130.516.0166

Schrumpf, Ellen 2018: Children and their Stories of WWII: A Study of Essays of Norwegian School Children from 1946. In: Reidar Aasgaard, Marcia Bunge & Merethe Roos (eds.), Nordic Childhoods 1700–1960: From Folk Beliefs to Pippi Longstocking. London & New York: Routledge, pp. 263–273.

Seitsonen, Oula 2018: Digging Hitler’s Arctic War: Archaeologies and Heritage of the Second World War German Military Presence in Finnish Lapland. Helsinki: Unigrafia.

Seitsonen, Oula & Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto 2018: “Where the f… is Vuotso?” Material Memories of Second World War Forced Movement and Destruction in a Sámi Reindeer Herding Community in Finnish Lapland. International Journal of Heritage Studies 24:4, 421–441. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1378903

Seitsonen, Oula, Vesa-Pekka Herva & Mika Kunnari 2017: Abandoned Refugee Vehicles “in the middle of nowhere”: Reflections on the Global Refugee Crisis from the Northern Margins of Europe. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3:2, 244–260. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1558/jca.32409

Seljamaa, Elo-Hanna & Pihla Maria Siim 2016: Where Silence Takes Us, if We Listen to it. Ethnologia Europaea 46:2, 5–13.

Sheftel, Anna & Stacey Zembrzycki 2010: “We started over again, we were young”: Postwar Social Worlds of Child Holocaust Survivors in Montréal. Urban History Review 39:1, 20–30. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7202/045105ar

Shuman, Amy 2006: Entitlement and Empathy in Personal Narrative. Narrative Inquiry 16:1, 148–155.

Siim, Pihla Maria 2016: Family Stories Untold: Doing Family through Practices of Silence. Ethnologia Europaea 46:2, 74–88.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty 1988: Can the Subaltern Speak? In: Cary Nelson & Lawrence Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 271–313.

Stewart, Kathleen 2007: Ordinary Affects. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Stone, Philip 2006: A Dark Tourism Spectrum: Towards a Typology of Death and Macabre Related Tourist Sites, Attractions and Exhibitions. Tourism: An Interdisciplinary International Journal 54:2, 145–160.

Tuominen, Marja 2005: A good world after all? Recovery after the Lapland War. In: Maria Lähteenmäki & Päivi Maria Pihlaja (eds.), The North Calotte: Perspectives on the Histories and Cultures of Northernmost Europe. Helsinki: Department of History, University of Helsinki, pp. 148–161.

Tuominen, Marja 2015: Lapin ajanlasku: Menneisyys, tulevaisuus ja jälleenrakennus historian reunalla. In: Ville Kivimäki & Kirsi-Maria Hytönen (eds.), Rauhaton rauha: Suomalaiset ja sodan päättyminen 1944–1950. Vastapaino: Tampere, pp. 39–70.

Väyrynen, Anna-Liisa 2012: Hukutetun kodin muistot: Lokan allasevakkojen kuvat ja esineet. In: Veli-Pekka Lehtola, Ulla Piela & Hanna Snellman (eds.), Saamenmaa: Kulttuuritieteellisiä näkökulmia. Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 91. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, pp. 52–66.

Welzer, Harald 2005: Grandpa wasn’t a Nazi: National Socialism and the Holocaust in German Memory Culture. New York: American Jewish Committee.

Werner, Emmy E. 2000: Through the Eyes of Innocents: Children Witness World War II. Oxford: Westview.

Author Biographies

Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto, PhD, is a researcher at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She is an ethnologist/folklorist by training and is interested in war heritage, everyday life in the post-war period, material culture, intergenerational exchange, narrative traditions, and cultural heritage work. One of her main publications is the monograph Her Own Worth – Negotiations of Subjectivity in a Life Story of a Female Laborer (2014, Finnish Literature Society).

(eerika.koskinen-koivisto@jyu.fi)

Oula Seitsonen, PhD, MSc, is an archaeologist and geographer at the University of Oulu and University of Helsinki, Finland. He completed his doctorate with a dissertation entitled Digging Hitler’s Arctic War – Archaeologies and Heritage of the Second World War German Military Presence in Finnish Lapland (2018, Unigrafia). His research interests cover a wide variety of subjects, ranging from prehistoric paleo-environmental studies to contemporary archaeology and digital humanities.